Wilkes University Archives is excited to announce that thanks to Garrett Berlin, a Junior History major minoring in Political Science, and Kaelin Hughes, a senior History and Political Science major minoring in Policy Studies, the American Figures series of the Gilbert Stuart McClintock collection is now processed and digitized.

Kaelin Hughes is a senior History and Political Science major with a minor in Policy Studies. On campus, Kaelin is a member of the Wilkes University Honors Program, a Resident Assistant, and the 2023-2024 recipient of the Dr. James Rodechko Scholarship in History. After graduating in May, Kaelin will be attending Duquesne University to complete her M.A. in History, with interests in American history and women and gender studies. Kaelin is interested in pursuing a career in research and academia to spread the love of history to future students.

The finding aid with digitized items can be found here. Below are Kaelin’s reflections.

The American Figures collection is a comprehensive collection of letters, autographs, and drawings/sketches from famous American individuals that stretch all the way back to the 18th century and others from the 20th century. This collection is a part of the overall McClintock collection donated by Wilkes-Barre native, lawyer, and author Gilbert Stuart McClintock.

This collection contains 99 letters, four sketches, and 77 autographs from a variety of American politicians, authors, and public figures. Other items include photographs of politicians and entertainers, and a short subseries concerning American Slavery.

The collection consists of a treasury of historical correspondence spanning the 18th and 19th centuries, delving into the intimate exchanges, personal reflections, and significant narratives that shed light on the lives and times of early American figures. These letters offer a window into the thoughts, aspirations, and challenges of individuals who shaped the course of American history. Many of the major themes seen throughout this collection include the subtle discussion of civil rights and liberties, as the collection houses letters and autographs from different activists. At first glance, these letters and autographs may not signal any messaging to their beliefs and activism. However, with further research, these letters reveal the rich lives and actions of each individual figure, providing us a new understanding of both well known and unfamiliar persons throughout American history.

Additionally, the collection reveals the nature of autograph and letter collecting of different figures, whether they were politicians, authors, or activists. The history of autograph collecting itself intersects with our collection, highlighting the surge of the hobby in the nineteenth century. Dissecting the language utilized within the letters reveals how figures responded to requests for their autographs as well as connected with fellow peers in politics, literature, and activism.

As mentioned, one of the major themes found within these letters is activism, most specifically ideas surrounding abolition, racism, and women’s rights. Additionally, we see these activists’ interests and activities outside of their renowned actions from later in their lives. This is seen through general, uplifting correspondence or conversations with artistic organizations.

The Abolitionist Movement and Addressing Racism in the United States

The institution of slavery in the United States began with the Atlantic slave trade transporting enslaved persons to British North America. Enslavers purchased and transported typically Africans to the states from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries. As a result, the United States generated numerous industries, such as tobacco and cotton, through exploitation of the enslaved. Over time, generations following the original enslaved persons that were transported to the U.S. continued to face the brutality of slavery (Schermerhorn, “A History of Slavery in the United States”).

Abolitionist sentiments were prevalent throughout the eighteenth century, with Quakers speaking out against the act and claiming it was a sin preventing all man from attaining welfare and happiness. These sentiments grew with calls to abolish the Atlantic slave trade. Although the slave trade was abolished in the United States in 1808, the institution of slavery remained legal and continued in the United States. Abolitionists continued advocating for freeing enslaved persons, through publications, poetry, music, and art (Library of Congress Exhibitions, “The African American Odyssey: A Quest for Full Citizenship”).

ACD May 2024 via Wikimedia Commons

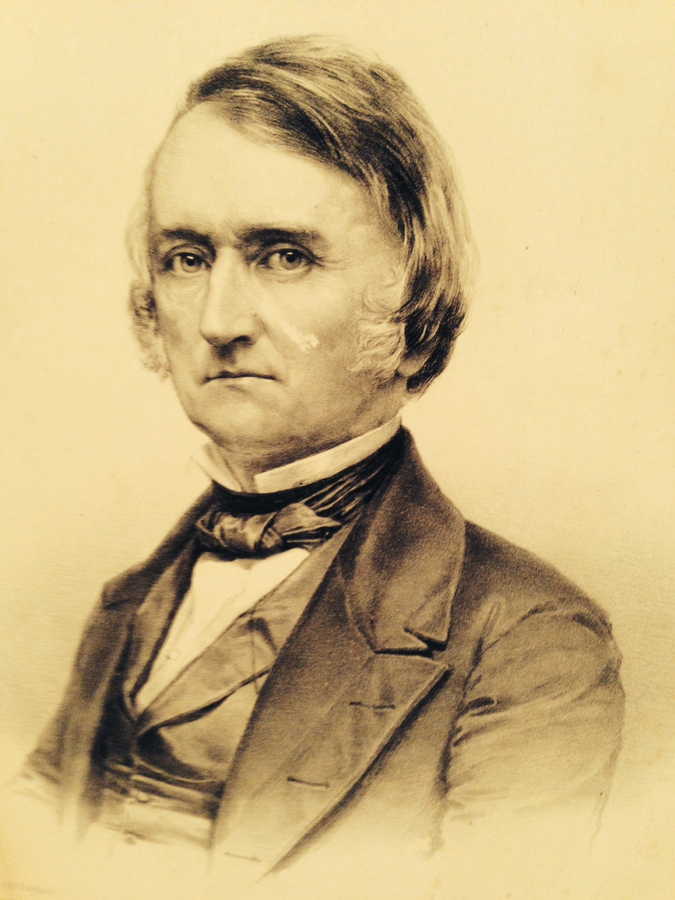

In Pennsylvania, abolitionists circles grew and networked with one another to advance the anti-slavery cause in the North. These abolitionists primarily included lawyers, intellectuals, clergy members, or local politicians. A prime example of a local figure involved in the abolitionist cause is William Jessup. A Montrose, Pennsylvania native, Jessup was a lawyer and judge within the Eleventh District of Pennsylvania, which was composed of Luzerne, Wayne, Pike, Monroe, and Susquehanna counties. Jessup was actively engaged in politics throughout his career, being involved at the Republican Party conventions which nominated Ulysses S. Grant and Abraham Lincoln to the presidency, respectively (The Scranton Republican, Judge William Jessup Obituary).

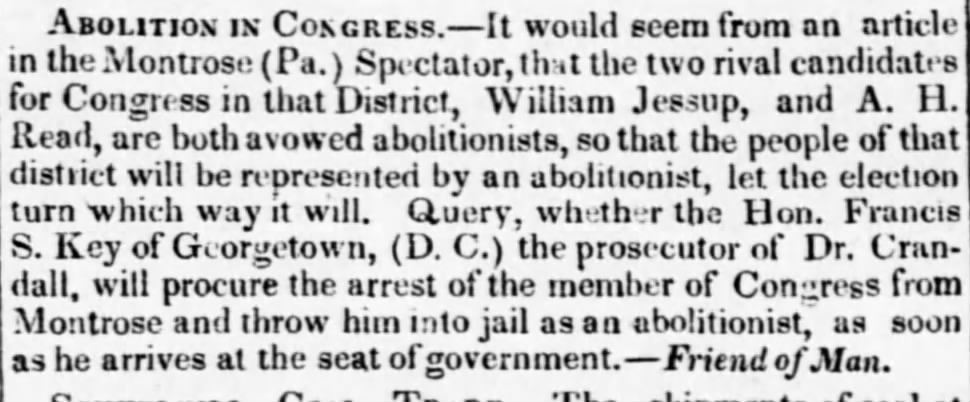

Jessup’s involvements reveal he was a staunch abolitionist throughout his entire career. Newspapers from the 1830s reveal that Jessup ran for Congress in his local district against another abolitionist candidate. Based on these clippings, it presents the growing sentiments throughout the North that the institution of slavery needed to be addressed at a nationwide level, aiming to protect African Americans.

“It would seem from an article in the Montrose (Pa.) Spectator, that the two rival candidates for Congress in that District, William Jessup, and A.H. Read, are both avowed abolitionists, so that the people of that district will be represented by an abolitionist…”

Additionally, Montrose is documented to have ties to the abolitionist movement and the Underground Railroad, making it a perfect environment for Jessup to express his anti-slavery sentiments. A former slave named Printz Perkins established a settlement in Brooklyn Township for African Americans, welcoming freed enslaved people and fugitives. Other formerly enslaved people settled in Montrose, one of which, Gabriel Chappell, who worked under Jessup. In conjunction with Perkins’ settlement, many locals formed the Susquehanna County Anti-Slavery Society, meeting to discuss the history of Susquehanna Country and condemn slavery, calling for immediate abolition (Eidenier, “A Journey Toward Freedom, Montrose Role in Breaking the Bondage of Slavery”).

As a result of Jessup’s involvements in law, politics, and his attitudes against slavery, he became a popular figure in Luzerne County. His reputation as both an abolitionist and religious leader are present in correspondence sent to him, requesting his presence to satiate the intellectual interests of the Wilkes-Barre community.

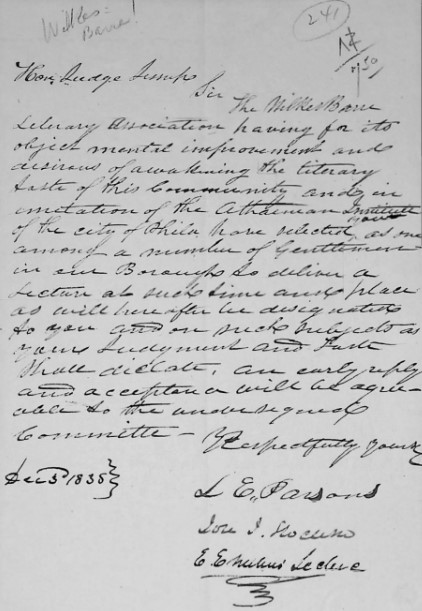

11.63 Item 63: Letter from Lewis E. Parsons et.al to Judge William Jessup, 1838 December 3

Sir

The Wilkes Barre Library Association having for its object mental improvement and desirous of awakening the literary taste of this community and in imitation of the Athenaeum Institute of the city of Phila[delphia] have selected you as one among a number of Gentlemen in our Boroughs to deliver a lecture at such fine and place as will here after we designated to you and on such subjects as your judgment and such have dictate, an early why and acception a will we argueable[sic, arguable] to the undersigned committee

Respectfully yours,

L[ewis].E[liphalet]. Parsons

Jon[athan] J[oseph] Slocum

E[dward] [Emelius] Le Clerc”

This 1838 letter from Lewis E. Parsons, politician and lawyer who trained in Wilkes-Barre, requested Jessup to speak at the Wilkes-Barre Library Association on the subject of his choice. However, Parsons also notes how this series of lectures is made to mimic The Athenaeum of Philadelphia, a membership library dedicated to connect with the “history and antiquities of America…to disseminate useful knowledge for the public.” Based on this comparison, it is evident that Parsons and other members of the Library Association, Jonathan Joseph Slocum and Edward Emelius Le Clerc, began showing interest in intellectualism and providing historically enriching opportunities for their members and locals.

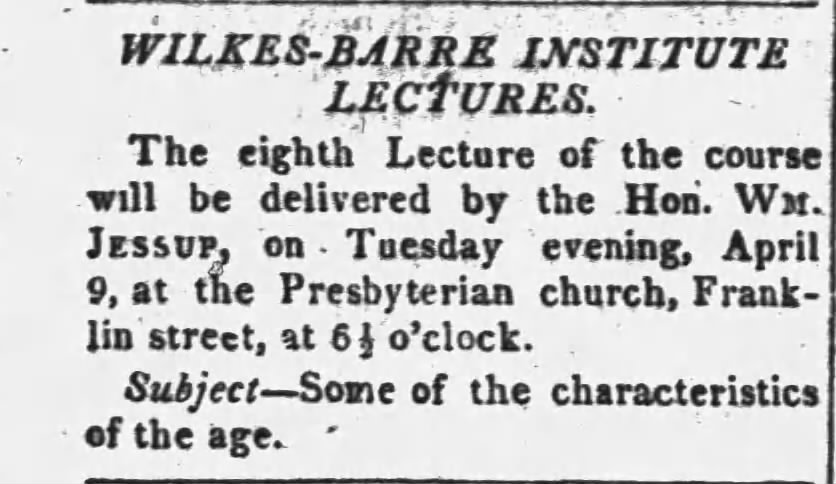

However, it is unsure of what Jessup’s lecture discussed. The Wyoming Republic announced Jessup’s lecture that occurred the following April in 1839 as the eighth in their intended series, stating the subject as “some of the characteristics of the age.”

Despite this vague language, it can be inferred that Jessup addressed the debate between slavery and abolitionism during the lecture, as it was a prominent issue during the “age.” The combination of Jessup’s history within abolitionists discussions and his lecture in Wilkes-Barre reveals his lasting activism throughout his life, as well as its connections with the area. It is vital to continue bridging historical narratives and preserving the history of the area, especially its involvement in the abolitionist cause. Although the letter to Jessup is unclear as to what he should discuss, his reputation and history of involvement in the cause displays Wilkes-Barre’s interest in spreading the ideas of the abolitionist movement before the Civil War.

Jessup continued fighting for abolition following his lecture in Wilkes-Barre, particularly in the political realm. As previously mentioned, Jessup was a loyal member of the Republican party. In 1855, Jessup was appointed as the President of Republicans of Pennsylvania, who met that year to discuss abolition and overthrowing the South’s continued exploitation of slaves. Despite their efforts, Democratic candidate James Buchanan was elected president in November the following year (American Abolitionists and Antislavery Activists, Conscience of the Nation, “United States Abolitionist and Anti-Slavery Organizations”).

Additionally, Jessup served on the Republican Party’s Committee on Platform and Resolutions for the 1860 party convention, delivering resolutions to the party. This platform called for the Republican party to triumph in the face of the “history of the nation during the last four years,” referring to the intensifying debate over slavery. The platform also states its commitment to the Declaration of Independence, the rights of states, addressing the South’s abuse of power towards enslaved people as a crime against humanity (Northern Illinois University Digital Library, “Proceedings of the Republican National Convention, 1860”).

William Jessup’s continued involvement in the abolitionist movement is emphasized through the correspondence directed to him housed within our collection. The letter acts to provide researchers with more information on Jessup himself, the intellectual interests of organizations in Wilkes-Barre during the nineteenth century, and revealing Wilkes-Barre’s involvement in the cause.

Following Jessup’s involvement in the growing abolitionist movement, tensions grew within the nation, specifically between the North and South regarding the constitutionality of slavery. Numerous legislative decisions perpetuated slavery, such as the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, as well as the Dred Scott case decision regarding enslaved persons as solely property. This conflict evidently came to a head with the election of President Abraham Lincoln, leading to the Civil War between the North and South.

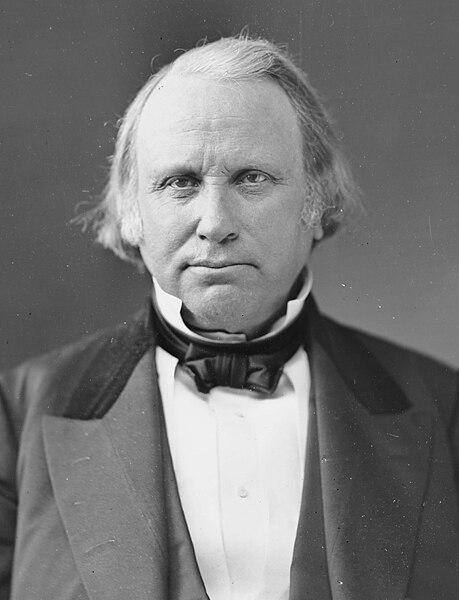

Correspondence in the collection from politician and former Vice President (1873-1875) of the United States Henry Wilson reveals his own personal reflections on the passing of a fellow abolitionist. Wilson maintained an interest in social and moral reforms throughout his life, beginning his political career in the Massachusetts state legislature in 1840, later being appointed to the U.S. Senate from the legislature. He was known for speaking against slavery, pushing President Lincoln to free enslaved persons, and supporting the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution (University of Virginia Miller Center, “Henry Wilson (1873-1875)”). Wilson’s letter within our collection demonstrates his unwavering support for the movement.

ACD April 2024 Via Wikimedia Commons

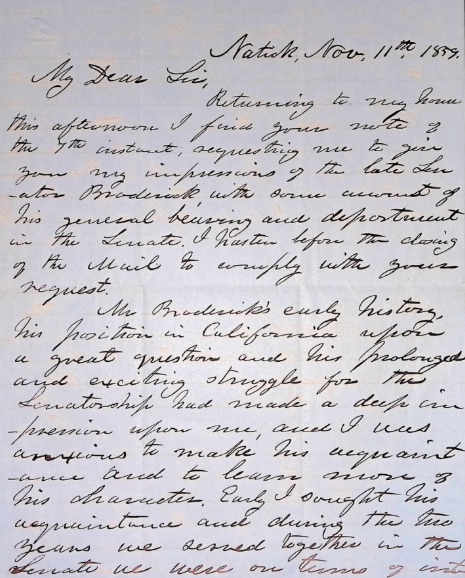

Transcription:

My Dear Sir,

Returning to my house this afternoon I find your note of the 7th instant, requesting me to give you any impressions of the late Senator Broderick, with some account of his general bearing and department in the Senate. I hasten before the closing of the mail to comply with your request.

Mr. Broderick’s early history, his position in California upon a great question and his prolonged and exciting struggle for the Senatorship had made a deep impression upon me, and I was anxious to make his acquaintance and to learn more of his character. Early I sought his acquaintance and during the two years we served together in the Senate we were on terms of intimacy. We were members of the same committee, often conferred together concerning public affairs, and entertaining sentiments in common upon many questions, we held free and unreserved intercourse with each other. Our acquaintance re[o]pened into a warm and sincere friendship. For him I entertained sentiments of respect and affection; and I deeply deplore his death, and shall ever cherish his memory.

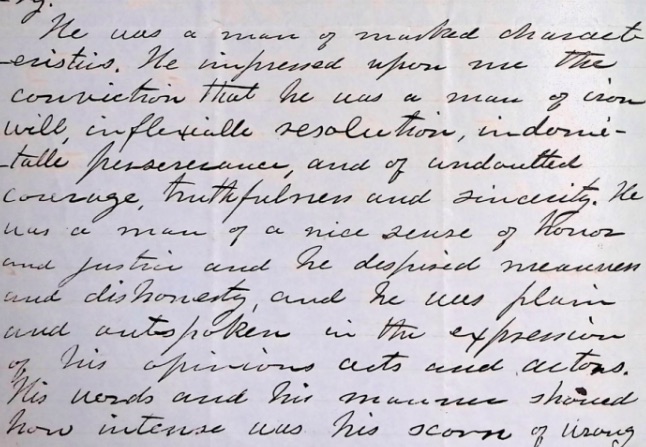

He was a man of marked characteristics. He impressed upon me the conviction that he was a man of iron will, inflexible resolution, indomitable perseverance and of undaunted courage, truthfulness and sincerity. He was a man of a nice sense of Honor and Justice and he despised mean men and dishonesty, and he was plain and outspoken in the expression of his opinions acts and act[i]ons. His words and his manner showed how intense was his scorn of wrong and wrong-doers. He was fearless, frank and out-spoken and I think he was sometimes imprudent in the utterance of his opinion.

Mr. Broderick had many great and noble mental and moral qualities and these qualities were being developed by study, reflections and a Larger experience with public affairs. His faults-vices he had none-were the faults of a manly, honest and robust nature. He mingled little with general society. There was a shade of melancholy about him. He seemed to feel that he was alone in the world. He looked not hopefully for the success of the principles which he deeply cherished. I sometimes thought he was saddened by the consciousness that he was about entering into a great content for the supremacy of the principle he entertained in his adapted stated, and that he must encounter the hostility of men who were seeking his overthrow if not his destruction.California his last in him a public man who was ever watchful of his interests and honor;- The country a true patriot, the cause of freedom a devoted champion and thousands a tried and constant friend.”

The following letter from Wilson to recipient and fellow politician John W. Dwinelle discusses Wilson’s feelings about Senator David Broderick’s passing. Sen. Broderick died in a duel against David Terry, California Chief Justice. Terry challenged Broderick to a duel after debate regarding his loyalties to abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Broderick’s death acted to create a martyr for escalating and starting the Civil War (Senate Historical Office, “Senator Killed in Duel”). Within the letter, Wilson notes the following about Broderick,

Wilson highlights his admiration for Broderick’s character, especially how he was outspoken about his beliefs. These “beliefs” that Wilson is referring to are likely referencing Broderick’s anti-slavery beliefs which resulted in his death. Wilson’s evident support for Senator Broderick directly aligned with his own abolitionist beliefs, displaying new insights into how politicians supported one another leading up to and during the Civil War. Additionally, it displays how Wilson remained loyal to his own beliefs concerning slavery.

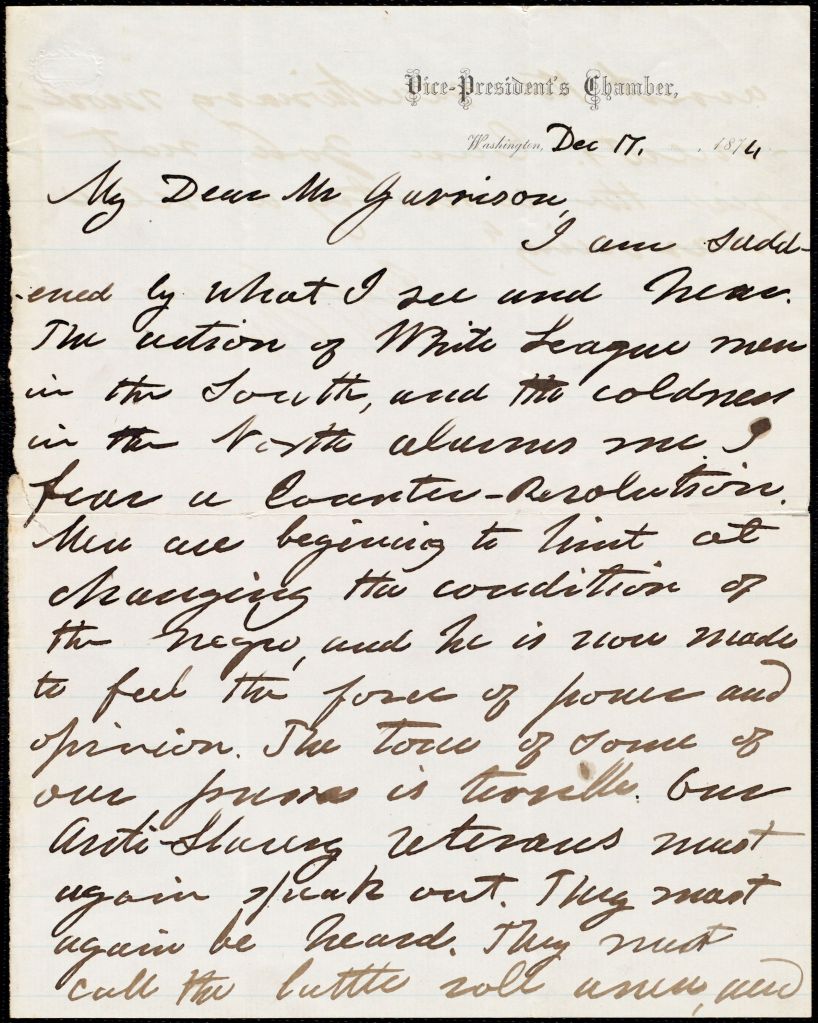

Following the war, Wilson continued to discuss his opposition to both slavery and racism in the United States, as seen in additional correspondence. In a letter to abolitionist and The Liberator founder William Lloyd Garrison, Wilson expresses his unhappiness with the nation with continuing tensions between the North and South.

ACD April 2024 via Digital Commonwealth, Massachusetts Collections Online

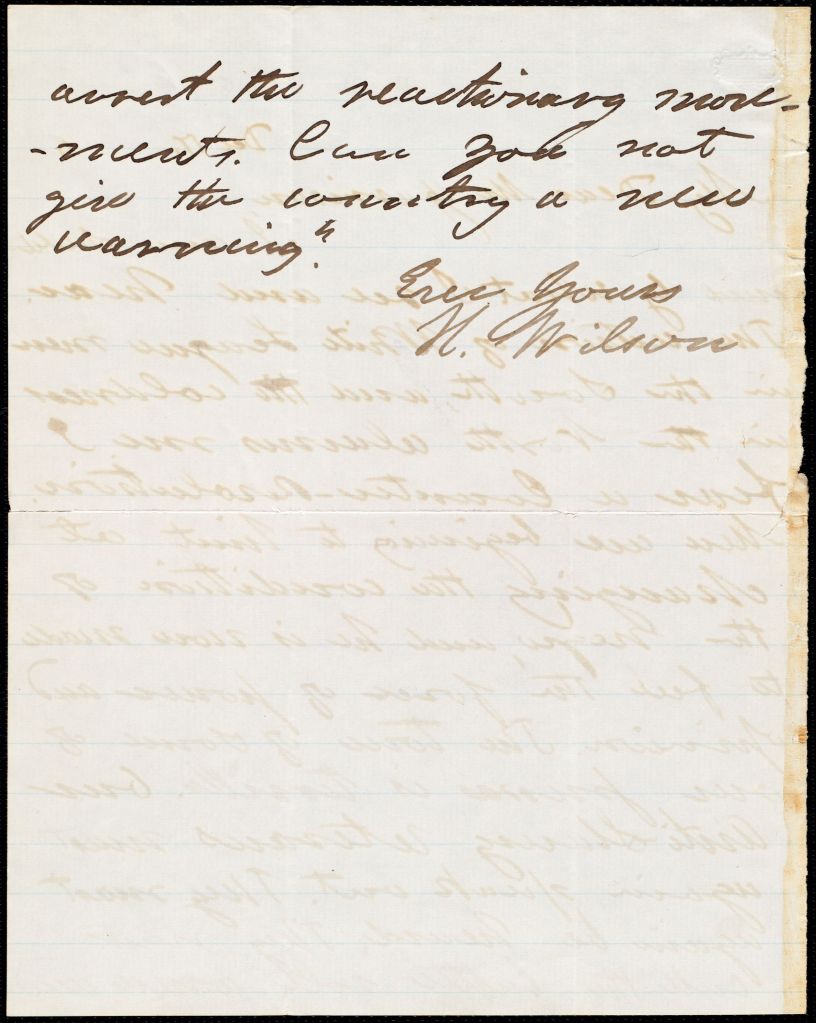

Transcript: “I am saddened by what I see and hear. The nation of White League men in the South, and the coldness in the North alarms me. I fear a counter-revolution. Men are beginning to hint at changing the conditions of the Negro, and he is now made to feel the force of power and opinion. The tone of some of our prisons is terrible. Our antislavery veterans must again speak out. They must again be heard. They must call the battle roll anew and arrest the reactionary movements. Can you not give the country a new warning? Ever Yours, H. Wilson”

More specifically, Wilson notes how the nation of the “White League Men” in the South combat with the North, as well as how he fears a “Counter-Revolution” in response to post-war life. He concludes that those who advocated against slavery should continue speaking out to ensure that progress is not lost. Combining Wilson’s initial perspective on Sen. Broderick and his words to Garrison reveal how he maintained his position against slavery and wanted to preserve the freedom that African Americans secured at the end of the Civil War. Furthermore, according to the Museum of Farmington History, Wilson went on to write a multivolume work on The Rise & Fall of the Slave Power in America, which reinforced his commitment to securing freedoms and ensuring there was no political backsliding.

Continuing the Fight: Activists for African-Americans in Post-Civil War America

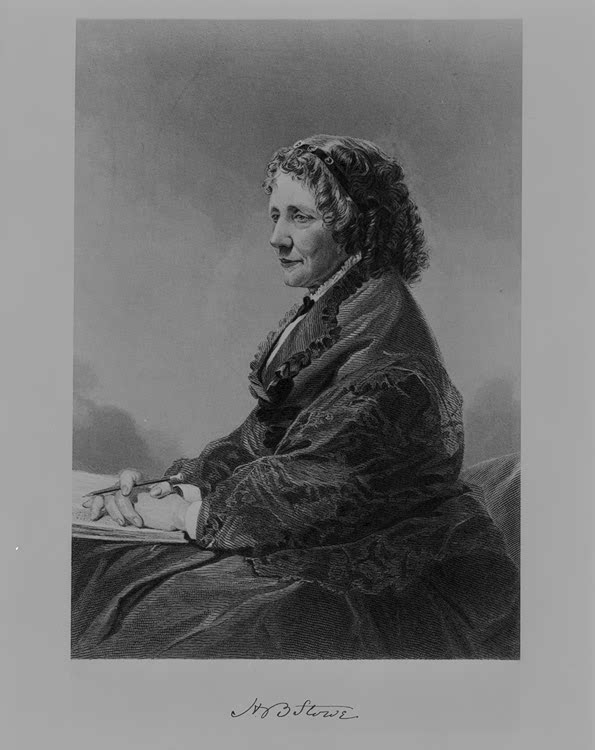

The Civil War resulted in the emancipation of enslaved persons across the United States, giving African Americans the ability to navigate their new freedoms. Additionally, it allowed numerous politicians and authors to see the progress they previously advocated for. One author of great importance to discussions on slavery in the United States is Harriet Beecher Stowe. Stowe is known for her abolitionist stories, most famously Uncle Tom’s Cabin published in 1853. Through these stories, Stowe aimed to show the disparities between the free and enslaved, with Uncle Tom’s Cabin following the cholera epidemic and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 (Michals, “Harriet Beecher Stowe”).

ACD April 2024 via Library of Congress

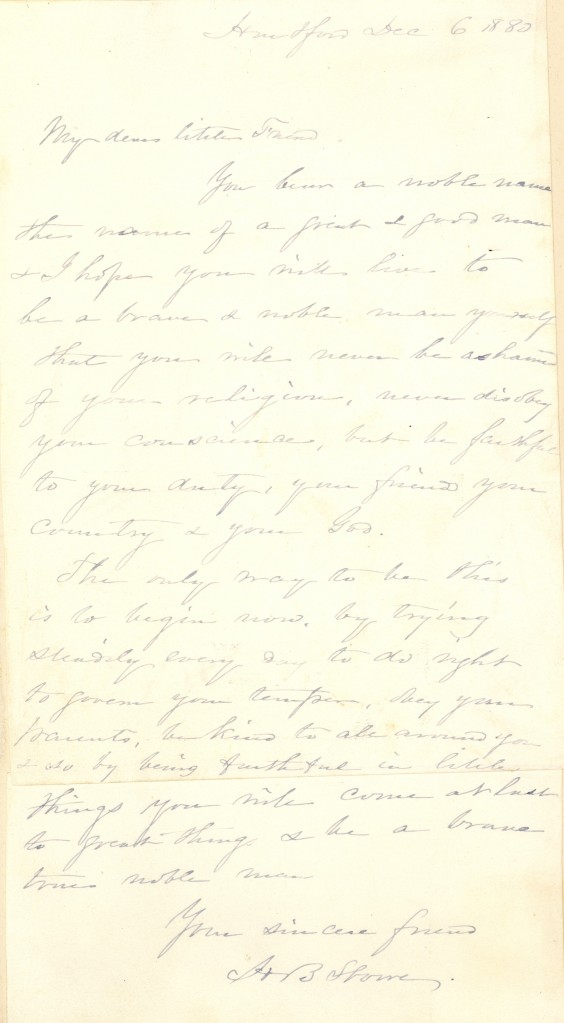

Stowe remained dedicated to the anti-slavery cause throughout her life, even after the Civil War. Stowe and her extended family believed that securing racial equality throughout the United States did not end with abolishing slavery. Her family opened schools in Florida to promote equal access to education for African Americans, and she also helped found the Hartford Art School (University of Hartford, “About Us”). Additionally, Stowe went on to speak across the country regarding progressive ideas in a post-slavery country (Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, “Life of Harriet Beecher Stowe”). There is minimal information on Stowe’s later life besides her speeches, but a letter within the collection highlights her benevolence and commitment to promoting the good in others.

The letter reads the following:

11.77. Item 77: Letter from Harriet Beacher Stowe to “My dear little Friend”, 1882 December 6

My dear little Friend

You bear a noble name the name of a great & good man & I hope you will live to be a brave & noble man yourself that you will never be ashamed of your religion, never disobey your conscience, but be faithful to your duty, your friend you currently & your God.

The only way to be this is to begin now. by trying steadily every day to do right to govern your temper, ober your parents, be kind to all around you & so by being faithful in little things you will come at last to great things & be a brave true noble man.

Your sincere friends

H. B. Stowe.

Stowe encourages the recipient of the letter to remain true to themselves while providing encouragement. She notes that through these things, the recipient will continue to do great things and be a noble man. It is unsure who this letter is for, however, it reveals Stowe’s continued commitment to promoting the good in others and ensuring that they can live to their full potential. Although there are minimal additional letters from later in Stowe’s life, this letter combined with her later feats of speaking on equal rights display’s her commitment to equal rights and uplifting others. Even if it is not a direct contribution to abolition or equality, her literary contributions and activism reveal her character.

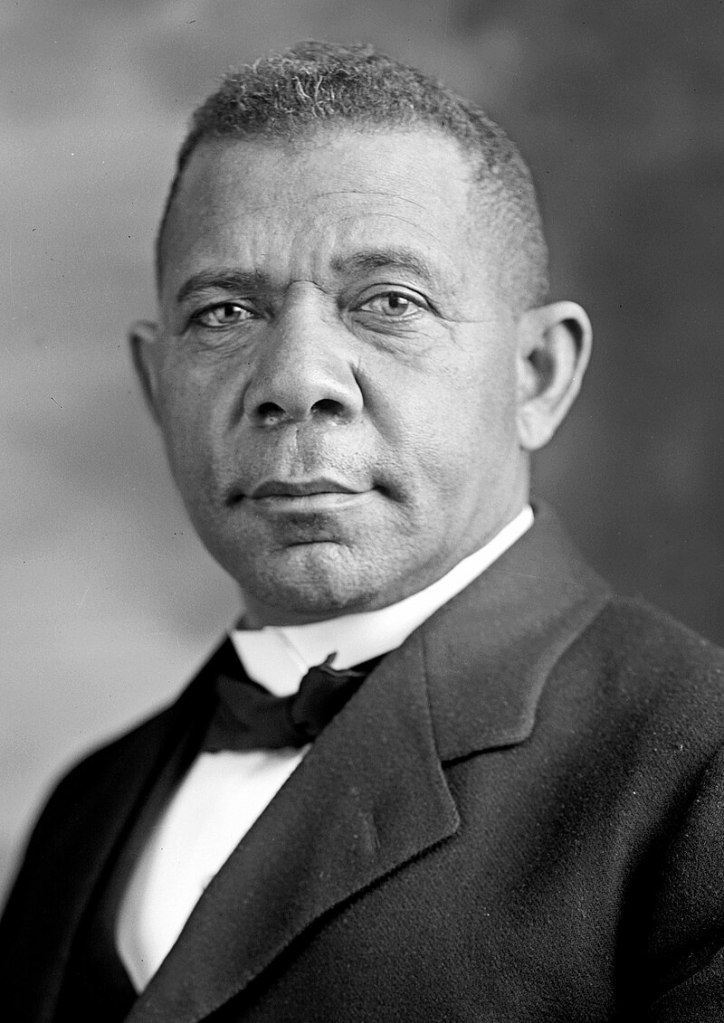

Another example of relationships that provide channels for continuing activism can be found in the correspondence of prominent educator and author Booker T. Washington. Washington was born into slavery and gained freedom under the Emancipation Proclamation. Through his freedom, Washington attained an education and went on to teach as founding principal and president of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, now Tuskegee University (Tuskegee University, “Booker T. Washington”).

ACD April 2024 via Wikimedia Commons

Washington is known for his ideas regarding African American integration into different professions in the United States. He believed that African Americans should establish themselves as more skilled and a candidate for the laboring class of workers rather than attempt to join white-collar jobs. His ideas conflicted with other African American activists, such as W.E.B. Du Bois, whom he worked with before his passing (Virginia Museum of History & Culture, “Booker T. Washington”).

However, his correspondence housed in the collection reveals another interest of Washnigton outside of his activism for African Americans. Booker T. Washington maintained an interest in art as a part of his interests to ensure African Americans accessed liberal arts education. Specifically, Washington wrote to trustee of the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art, Charles Dana.

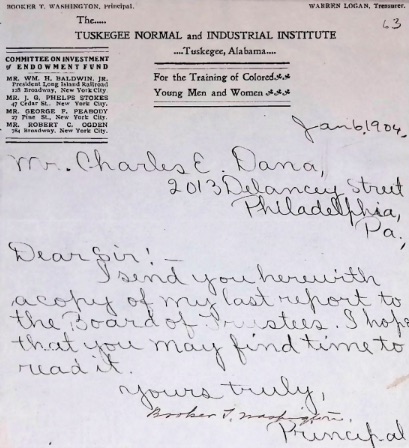

11.85. Item 85: Letter from Booker T. Washington to Charles E. Dana, 1904 January 6.

Dear Sir: –

I send you herewith a copy of my last report to the Board of Trustees. I hope that you may find time to read it.

Yours truly,

Booker T. Washington, Principal

Within the following letter, Washington tells Dana how he had enclosed a report to the Board of Trustees for the school. It is unsure of what this report entailed. The recipient, Charles E. Dana, was an educator at the University of Pennsylvania and heavily involved in the Philadelphia art scene.

Furthermore, the Museum, now known as the University of the Arts, began as an institution to respond to growing interest in art and education in the latter part of the nineteenth century (University of the Arts, “History”). Based on this knowledge, it can be concluded that Washington had connections with the institution as a way to advance his cause. Washington remained committed to ensuring that African Americans could access educational opportunities within the arts, so maintaining a connection between Tuskegee and the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art shows potential for advancing his cause. This is not a well known relationship between Washington and the institute, therefore, highlighting such a connection provides guidance for future research in both Philadelphia, Tuskegee, and African American history to bridge all three together.

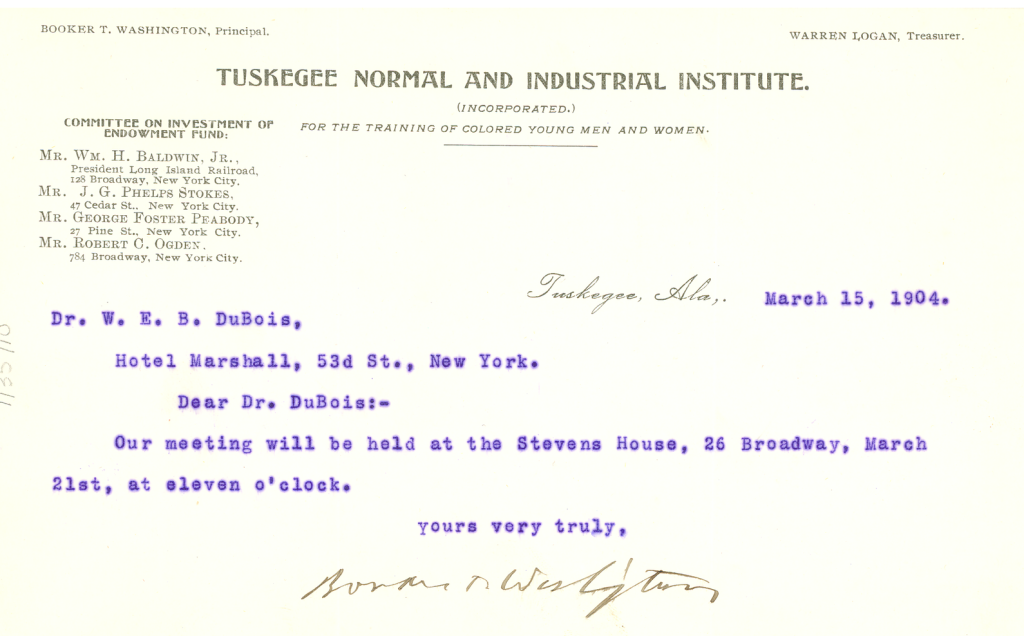

Washington’s connections with the art institute is only one of his many ventures during the beginning of the twentieth century. Washington developed a “Committee of Twelve” to advance African American interests in the United States, which he frequently wrote to W.E.B Du Bois about, even though they disagreed on measures to address racial inequality. This committee served to help clear and direct opportunities in the country to advance the lives of African Americans. Through their work, they would develop efforts to assist African Americans and “correct errors and misstatements” that held them back (Aptheker, “The Washington-Du Bois Conference of 1904”). Additional correspondence based out of Tuskegee to Du Bois reveals details about upcoming meetings of the committee.

ACD April 2024 via University of Massachusetts-Amherst Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center

Through his correspondence with both the art institute and Du Bois, it is evident that Washington remained loyal to his cause and sought out connections to see his ideas come into fruition. His overall goal was the advancement of African Americans in the United States and his letters to other American figures display his efforts. Unknown connections between Alabama and Pennsylvania reveal Washington’s continued commitment to uplifting African Americans and alleviating differences and difficulties of opportunity. In conjunction with Washington’s known relationship and correspondence with other prominent figures during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it is evident that his letters provided better avenues for the improvement of African Americans in attaining social equality.

Women’s Rights and Activism in the Nineteenth Century: Branching from Abolitionism

Women’s rights and advocacy also grew during the nineteenth century, usually in tandem with abolition and equal rights for African Americans. Many activists maintained moral positions that both African Americans and women should have greater freedoms in society such as voting rights, access to education, and other political and economic reforms. Advocacy for women’s rights primarily exploded following the Civil War, when activists Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton organized the Geneva Convention to discuss women’s rights, specifically the right to vote (Library of Congress, “Women’s Suffrage in the Progressive Era”).

However, many of these women were involved in abolitionist discussions, but excluded based on their gender. These women moved on to suffrage following inspiration from around the world. For example, the British Chartist movement, which advocated for workers rights and representation, inspired Stanton and Anthony to pursue women’s rights in the United States (Marino, “The International History of the U.S. Suffrage Movement”).

The true beginnings of the suffrage-focused women’s rights movement began around the end of the Civil War. Abolitionist women like Lucretia Mott shifted their involvements from Anti-Slavery Societies to women’s rights to promote women’s continued involvement in all political conversations. Mott specifically helped organize the Seneca Falls convention and was the first president of the American Equal Rights Association in 1866 (National Women’s History Museum, “Lucretia Mott”). However, based upon her letters and involvement in early discussions, it is evident that Mott had plans to shift her advocacy toward the Equal Rights Association years prior.

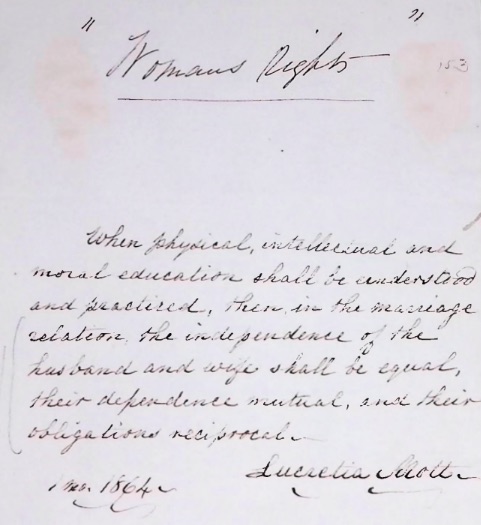

11.61. Item 61: A Draft of “Woman’s Rights” by Lucretia Mott, 1864 November 1.

This draft from Mott describes what she envisions as women’s rights in the United States. She describes how women will have equal opportunities for physical, intellectual, and educational progress, as well as the ability to practice what they have learned. From there, women will be equal to men, especially under the institution of marriage. Mott’s words on women’s rights likely are a continuation of the Seneca Falls convention, specifically elaborating on the Declaration of Sentiments by Elizabeth Cady Stanton. The declaration noted that society has a history of “injuries and usurpations” toward women and forcing them to live a dependent life. Although the Sentiments echoed with the parties at the convention, the only resolution to not pass was women’s suffrage (Digital History, “Women’s Rights”).

It is likely that Mott drafted this declaration about women’s rights to further spread and emphasize how women’s rights would be granted specifically through the right to vote. More specifically, moral education constitutes learning about moral and social norms, which would call for women to be more involved in society, outside of their private, domestic sphere of living. Allowing women to have greater access to education meant that they should be able to practice and apply the skills and knowledge they learned outside of their homes. The letter serves as a basis for her future advocacy, as seen in correspondence with fellow women’s rights activists.

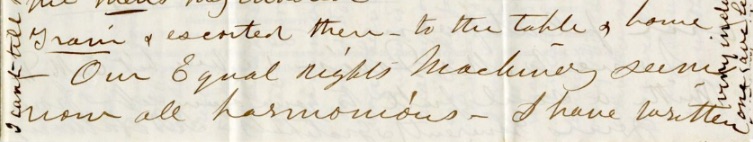

The following letter from Susan B. Anthony to Mott describes soliciting letters from different “good” people she thinks are worthy of being asked.

ACD April 2024 via Mott Manuscripts in Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College, Identification Number A00182173_SBA

Transcription: “Our Equal rights Machinery seems now all harmonious — I have written…”

It is unclear as to what these parties are being solicited for. However, Anthony mentions a press dinner later that week, where women will pay their own dinner bills although men are also attending said event. It is apparent that Anthony and Mott were employing different strategies to gather support for the women’s rights movement, such as contacting different persons and asking for their endorsement of their actions to advance the cause.

Similarly to Booker T. Washington’s continued commitment to his work, Mott’s loyalty to women’s rights did not waiver and she continued playing a major role in the movement up until her death. Her manuscripts reveal her inner thought process of women’s rights, drafting her beliefs to share and pursue within the Equal Rights Association and involvement with other prominent suffragist leaders.

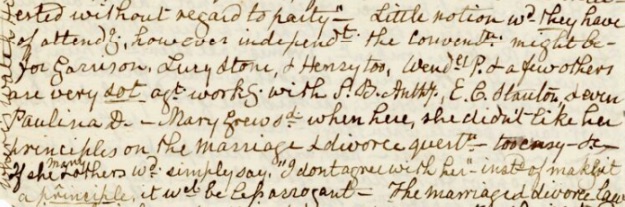

Lucretia Mott did not always agree with or want to continue working with other suffragists. Letters from the following year addressed to fellow suffragist Martha Coffin Wright reveal her reluctance to attend a convention in Boston due to tensions between other suffragists. She specifically highlights how other abolitionists and suffragists do not wish to work with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, or Paulina Wright Davis because of disagreements on marriage and divorce.

ACD May 2024 via Mott Manuscripts in Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College, Identification Number A00182261

Transcription:

“without regard to party– Little notion would they have of attending, however independent the Convention might be— for Garrison, Lucy Stone & Henry too, Wendell Phillips & a few others are very set against working with Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, & even Paulina Wright Davis — — Mary Grew said when here, she didn;’t like her principles on the marriage & divorce quest[ion] — too easy & If she & many others would simply say, “I don’t agree with her” — instead of making it a principle, it would be less arrogant — the marriage & divorce law…”

During the 1860s, Stanton and Anthony advocated for women to have greater access to divorce and allow women greater freedom within the institution. The pair spoke out against violence against women, such as bigamy, abuse, sexual abuse, among other crimes, arguing that men treated their wives as property rather than with morality (Griswold, “Law, Sex, Cruelty, and Divorce in Victorian America, 1840-1900”). It is interesting how other activists did not agree upon sentiments regarding women’s protections in marriage. However, Mott’s words resonate with how the movement should move forward. Mott noted how these women should respectfully disagree but attempt to move forward and secure protections of some kind. That way, women will still have room to advance in American society. Mott’s words effectively presented her commitment to the cause and discussed the women’s rights cause, even if she was not directly attending conferences.

General historical narratives tend to focus on suffrage as the primary right which women advocated for in the late nineteenth century. Despite this, access to these manuscripts reveal the complexity of the struggle for women’s rights. Women wanted equality of opportunity through not only politics, but all aspects of life. Women advocated to exit the private sphere of living. Despite this, not all women agreed on the terms and conditions for women’s greater participation in society, as seen in Mott’s letters. However, she still remained loyal to the movement with her involvement in local organizations.

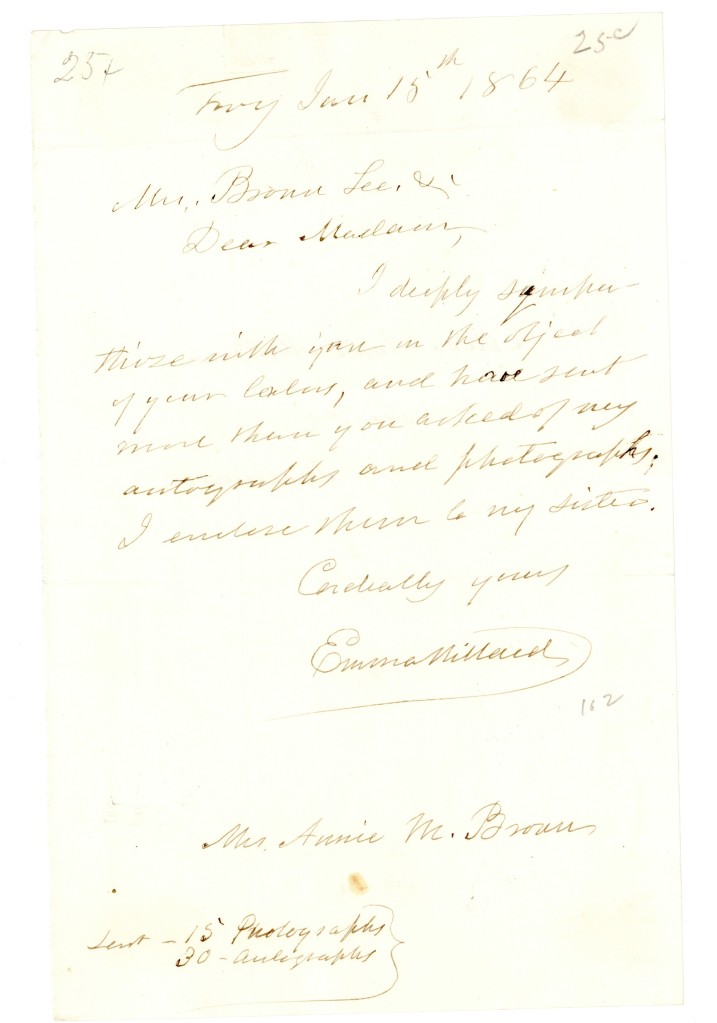

More specifically, it is pertinent to highlight how activists heavily campaigned for and organized equal access to education throughout the nineteenth century. Numerous suffragists became involved in founding different educational institutions, both solely for women or for both genders. Lucretia Mott was one activist involved in this venture through establishing Swarthmore College (Michals, “Lucretia Mott”). Our collection houses letters from numerous activists for women’s education, one of them being Emma Willard.

ACD April 2024 via Wikimedia Commons

Willard was an earlier activist for women’s education prior to the Civil War. She had the privilege of being educated in her New England residence, eventually founding the first female seminary school in 1821 at Troy, New York. Throughout her life, Willard published numerous documents targeting women’s education and the Civil War. Some titles include A Plan for Improving Female Education, History of the United States, and God Save America. There is limited information available on Willard’s works and her contributions, but her correspondence provides insight into her popularity and reverence later in her life (National Women’s Hall of Fame, “Emma Hart Willard”). Similarly to activists for racial equality, Mott slowed down her activity later in her life, but continued to engage with others regarding her views.

The following letter from Willard states that she has enclosed numerous autographs and photos from herself to recipient Annie Brown (not Annie Brown, daughter of John Brown). She is responding to an unknown situation Brown disclosed in the previous correspondence to her. However, it can be implied that Brown supported Willard in her efforts toward female education. Additionally, based on biographical information on Willard, she focused on travel and writing later in her life (around when this letter was written), returning to Troy as needed for the school (National Women’s Hall of Fame, “Emma Hart Willard”).

11.92. Item 92: Letter from Emma Willard to Annie M. Brown, 1864 January 15

Mrs. Brown Lee & Dear Madam,

I deeply sympathize with you in the object of your labors, and have sent more than you asked of my autographs and photographs. I enclose them to my sisters.

Cordially yours.

Emma Willard”

Willard evidently understood her impact on women’s rights discussions during the nineteenth century, happily fulfilling requests for autographs. Additionally, with research on autograph collections (that will be highlighted in the following sections), Willard’s correspondence exposes how different political figures, authors, activists, and entertainers addressed their popularity and requests from others.

While Willard’s letters provide insight into her popularity, there is a gap in the knowledge about Willard herself aside from her writings and involvement in founding the Emma Willard School. This may be due to Willard being an older figure in the community as the movement gained traction in the latter part of the nineteenth century, as Seneca Falls occurred and brought significant attention to the movement in 1848. Additionally, it is noted that Willard was not a direct supporter of the early suffrage movement, prioritizing education over everything else within the women’s rights movement (Lake Champlain Maritime Museum, “Vermont and the Fight for Suffrage”).

Although Willard was not a direct supporter of suffrage, it is still important that more information is uncovered about her life and her beliefs regarding women’s rights. It is important to continue bridging this gap and ensuring there is a fuller understanding of her contributions to women’s rights, providing the most cohesive picture of nineteenth century activism for women. Without such research, we cannot fully understand all aspects or arguments surrounding women’s rights, education, or suffrage in the United States.

The general correspondence subseries reveals new cognizance of both the daily proceedings of American figures, but how these letters fall into their occupations. These letters reveal that the figures maintained their beliefs through their correspondence, specifically their social activism. These American figures continued to advocate for abolition and equal rights on the basis of both race and gender within their letters. Additionally, finding additional context for their letters and how they fall into major events, such as the Civil War, provide researchers with new, deeper understandings of nineteenth century America.

Correspondence is not the only measure in which we can gather further insight into the lives of American figures. These letters provide both a way to highlight the personal interactions of these people and help build on existing historical narratives, but they also provide insight into the intentional actions of these figures in response to public phenomena and growing hobbies. This can be seen specifically in the autographs section of the collection, as numerous figures highlight how people requested their signature or used this request to their own advantage.

The second subseries within the collection is a vast collection of various autographs, ranging from 1720 to 1865. These autographs primarily highlight different politicians between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, with other autographs including lawyers, businessmen, or political activists. However, when comparing the autographs with items from the Correspondence subseries, there is an evident narrative present revealing the nature of autograph collection and preserving early American history.

The Origins of Autograph Collecting

The concept of Autograph collecting dates back to 322 B.C., as many collected Greek philosopher Aristotle’s manuscripts to pass down to their heirs. Other scholars passed down these manuscripts, collecting more and more from different philosophers along the way. Consequently, in the fourth century B.C., the Library of Alexandria was constructed to collect the greatest works of scholars and promote knowledge in philosophy, mathematics, science, medicine, history, and literature. Although these manuscripts were not necessarily what is commonly seen as an autograph of just a signature today, they held major significance to people because of their direct relationship to scholars (Raab Collection, “The History of Autographs: The Lure of Collecting”).

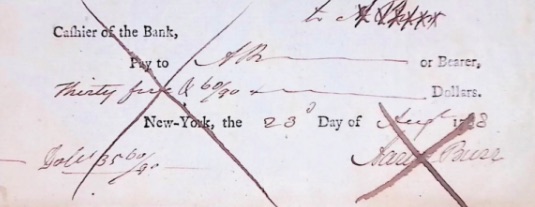

Specific signature autograph collection grew in the 16th century as a Dutch and German tradition. Friends would exchange different books among themselves to collect signatures, messages, illustrations, and more. These books traveled as many immigrated to the United States during the 19th century, beginning to popularize collections in the country (University of South Florida Libraries Autograph Collection). This spark in autograph collecting began with William B. Sprague, as he came into a collection of letters from the Washington family. Therefore, collections accumulated of the founding father’s signatures or documents, such as the following from Aaron Burr and John Hancock. They reveal the day to day activities of prominent American figures, or clippings of legislation or important documents.

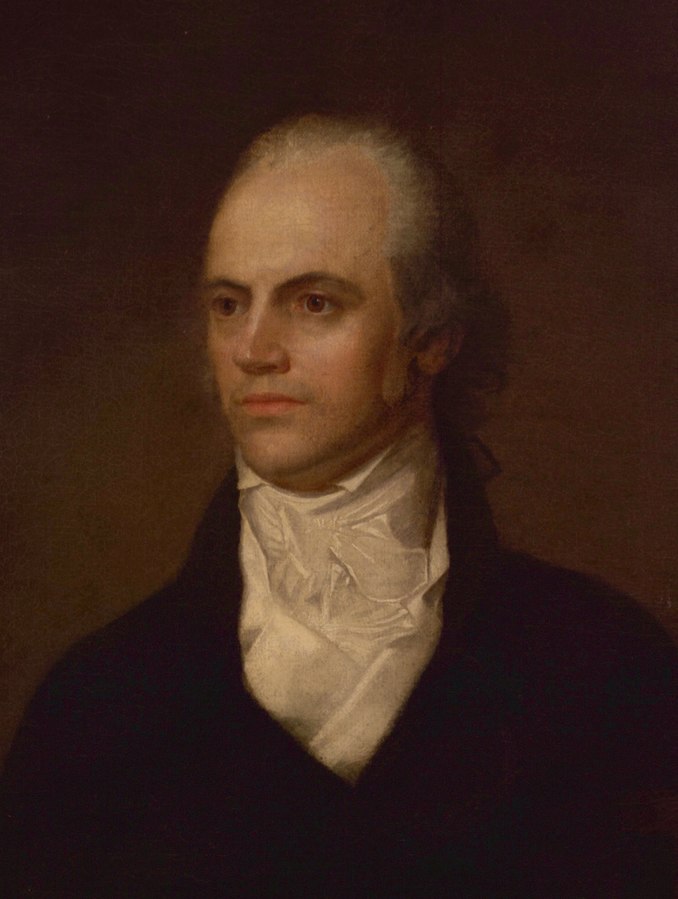

The following item below is a check from Aarron Burr, most famously known as the third Vice President of the United States under Thomas Jefferson, to an unknown “A.B.,” likely himself. When looking at Burr’s life in 1788, he was not in public office. He worked as a practicing lawyer in between his term in the New York State Assembly and his appointment to New York State Attorney General in 1789 (American Battlefield Trust, “Aaron Burr”). Although Burr was not politically active at the time, there is still significant appeal to collect his signature or documents because of his previous activity, acting as the genesis of autograph collection in the American context.

ACD April 2024 via Wikimedia Commons

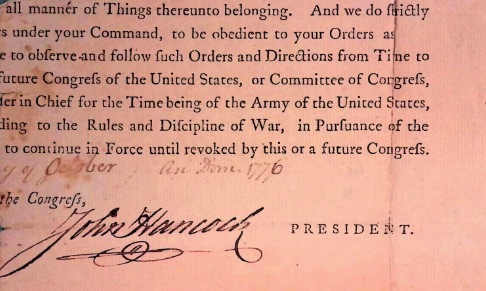

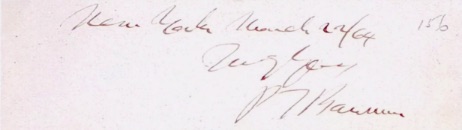

Another prime example of early autograph collection in the United States is the following signature from John Hancock. The following document is a clipping of proceedings of Congress (Hancock served as president of the Continental Congress at this time), dated in October 1776. Although the clipping primarily focuses on Hancock’s signature, it reveals how the government handled orders concerning battles during the Revolutionary War.

The following document has numerous cut off lines, but reads the following:

“And we do strictly… Under your Command, to be obedient to your Orders as… to observe and follow such Orders and Directions from Time to…. In Chief for the Time being of the Army of the United States… to the Rules and Discipline of War, in Pursuance of the… to continue in Force until revoked by this or a future Congress.”

Based on this document, this is likely an issuance assuring President George Washington, who served as the Commander in Chief of the Continental Army in 1775, that Congress will follow his orders concerning military operations, before or after the Battle of White Plains in New York state (George Washington’s Mount Vernon, “General Washington in the American Revolution”).

The Battle of White Plains took place during the New York Campaign of the Revolutionary War, and ended in defeat for George Washington and the Continental Army. Prior to this, Washington ordered that troops retreat from Manhattan (George Washington’s Mount Vernon, “Battle of White Plains”). It is likely that following or during this battle, Washington sent orders to Congress concerning the progression of war. Although this is merely a clipping of Hancock’s signature, finding its context shows the Congressional proceedings during the Revolutionary War, proving that autographs provide excellent insights into the past of the eighteenth and nineteenth century.

Autograph Collection as a Hobby and Business Model

Following the popularization of autograph collecting, the hobby then targeted living authors and politicians. In the mid to late nineteenth century, the hobby’s popularity exploded, and almost every public figure had an autograph circulating within one’s collection or passed around to other hobbyists (Raab Collection, “The History of Autographs: The Lure of Collecting”). These figures evidently caught onto the idea of autograph collection, using their signature to pass along notes or ideas as well. This can be seen in the known autographs by author, women’s rights activist, and abolitionist Lydia Maria Child.

ACD April 2024 via Wikimedia Commons

Lydia Maria Child was most famously known for her progressive literature throughout the nineteenth century, as well as forming the first children’s magazine, The Juvenile Miscellany. She is known for her poem Thanksgiving Day, known for its line, “over and river and through the wood…” Her works gained massive popularity and controversy through its social ideas, as they addressed racism. Specifically, Child addressed the topic through depicting interracial marriage between a main character Hobomok and an indigenous man against the family’s wishes. Additionally, Child published a second novel from the perspective of two female patriots before the American Revolution (Poetry Foundation, “Lydia Maria Child”). Evidently, Child was “radical” and progressive for her time.

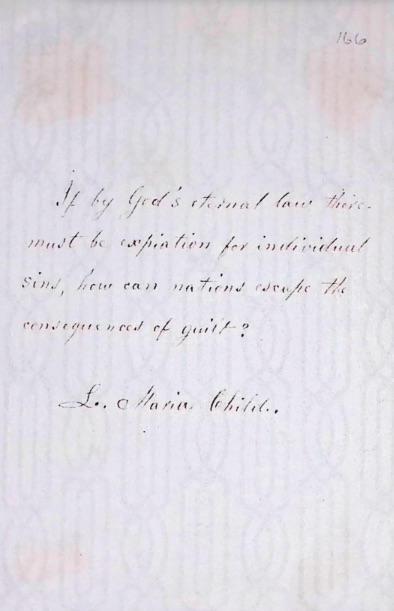

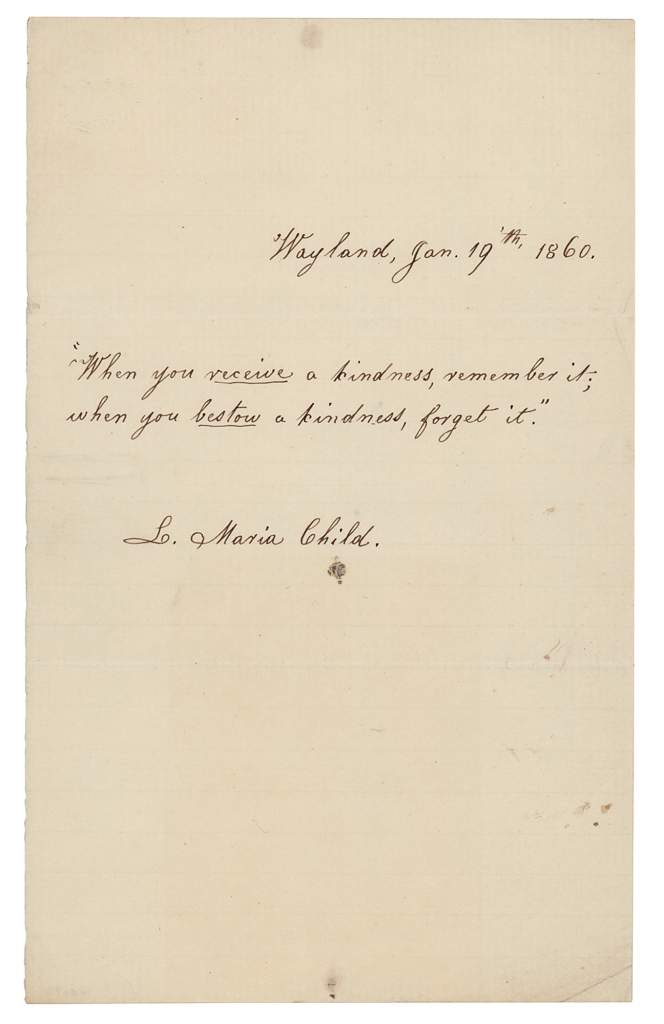

The following autograph from her reads, “If by God’s eternal law there must be expiration for individual sins, how can nations escape the consequences of guilt?” Child tended to give a quote with her signature, as seen in different, authenticated listings online. She usually included thought provoking quotes on kindness and tolerance, likely sharing quotes she resonated with and lived by through her writings.

ACD April 2024 via RR Auctions

The following quotation reads, “When you receive a kindness, remember it; when you bestow a kindness, forget it.” Through her signature, Child sets the expectation that people should remember those who have been kind to them, but not boast about their kindness to others. It evidently shows that Child was aware of the hobby, using it to her advantage to spread her views through these different quotes. Historians, as well as scholars in English literature, can look back and see how Child remained loyal to her beliefs through her works, activism, and correspondence with those wishing for autographs.

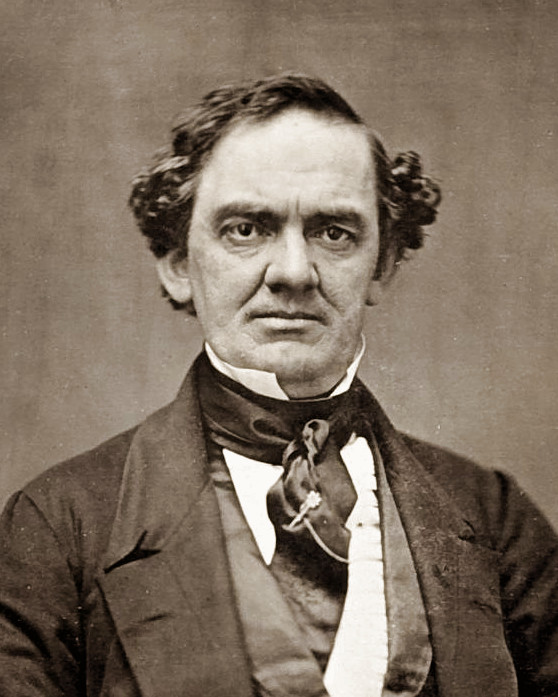

Another figure who caught onto the popularity of autographs, or generally fame and attention, was P.T. (Phineas Taylor) Barnum, the American showman most famously known for founding the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Barnum was known for being excellent at advertising and enticing audiences to come and see his shows with different oddities and curiosities (such as people or artifacts). Barnum latched onto the idea of worldwide fame and popularity, doing whatever possible to gain attention. For example, Barnum advertised African American woman Joice Heth for her alleged old age and talents, but claimed she was a mechanical figure when her popularity diminished (Mangan, “P.T. Barnum: An Entertaining Life”).

ACD April 2024 via Wikimedia

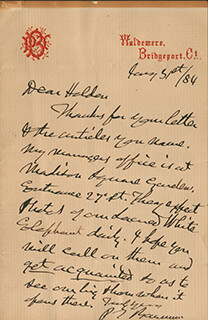

Barnum’s popularity resulted in others writing to him to praise his business or to network with him. Letters from 1884 reveal how Barnum responded to letters and information, pushing senders to watch his future shows.

ACD April 2024 via History for Sale

Transcription: “Thanks for your letter & the articles you name. My managers[sic] office is at Madison Square Garden, Entrance 27th St. They expect photos of our Secured White Elephant daily. I hope you will call on them and get acquainted so as to see our big show when it opens there.”

Barnum evidently understands the weight of his words due to his accolades, as he pushes the recipient of the letter, an unknown person named Halden, to become friendly with his own managers of the circus. By encouraging senders to become more involved in the “professional” aspects of his business, Barnum utilizes his responses and autographs as a rhetorical strategy to promote more attention toward himself and the Ringling Bros. Circus. Barnum plays into the ideas of autograph and letter collecting of popular figures to respond to fans, but also generate more traction for his business. Based on Barnum’s life and business practices, this is not unorthodox, as he exaggerated his “oddities” to generate the most attention at a given time. Compared to Child, Barnum takes a selfish approach to the autograph collection hobby instead of using the practice to spread positivity.

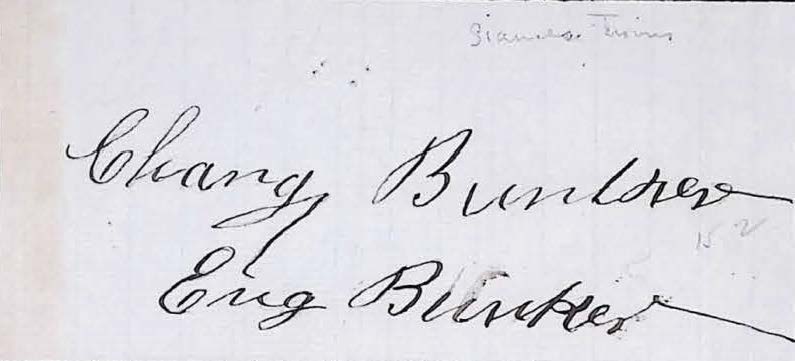

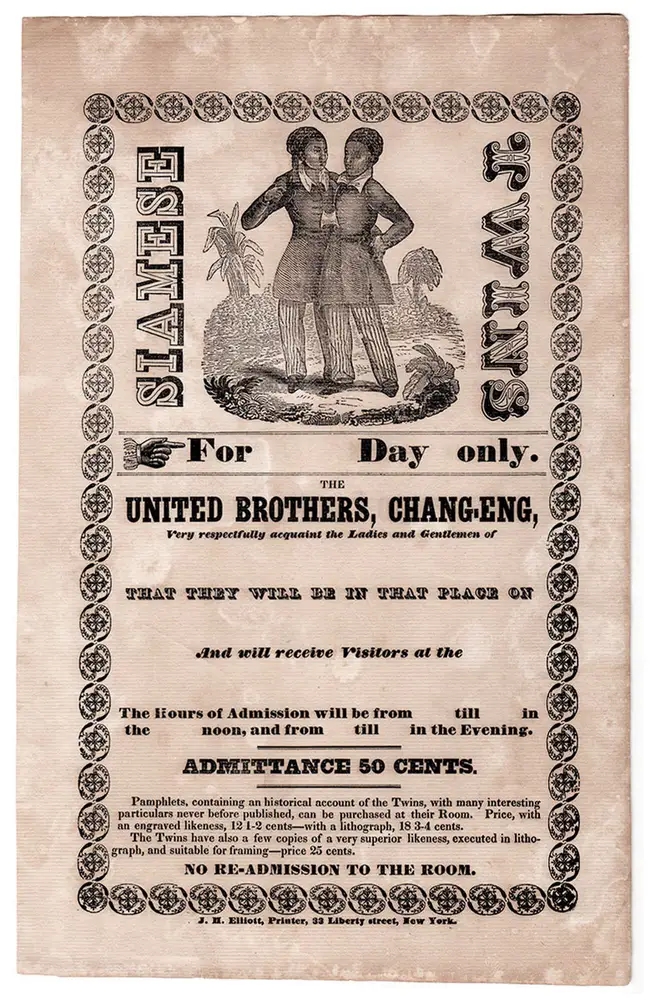

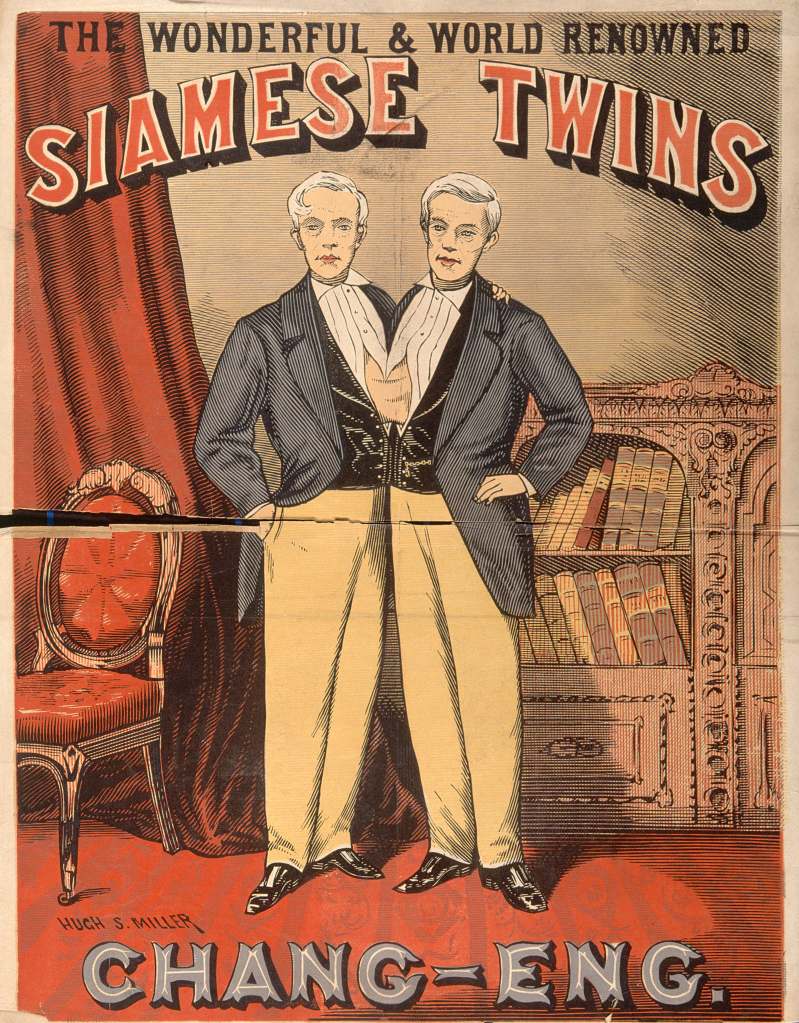

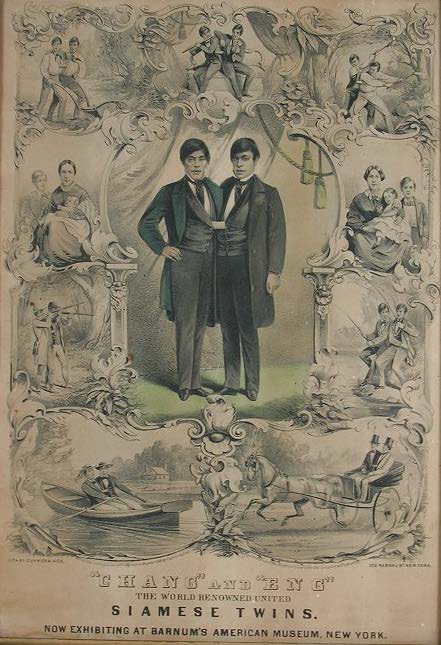

Aside from P.T. Barnum, the entertainment industry generally understood the value of their signatures and letters to fans and prospective partners. These parties ranged from big faces like Barnum, other parties involved in operations, or the talent themselves. Additional autographs that fall into the entertainment industry as well as appealing to autograph collection come from Siamese conjoined twin brothers Chang and Eng Bunker.

11.107. Item 107: Autograph from the Chang and Eng Bunker (Bunker twins), ca. mid-19th century.

The brothers were born in Siam (now known as Thailand) and were brought to the United States in 1829. They were widely exhibited as curiosities and were “two of the nineteenth century’s most studied human beings.” Newspapers and the public were initially sympathetic to them. They would go on tours to present and display themselves. In 1839, after a decade of financial success, the twins quit touring and settled near Mount Airy, North Carolina. They became American citizens, bought slaves, married local sisters, and fathered 21 children, several of whom accompanied them when they resumed touring.

Many anonymous promotional pamphlets were printed picturing the Bunkers in artwork and literature, comprising early fiction pieces on the “Siamese twins”; the twins were used more metaphorically in later works. Samuel Clemens (aka Mark Twain) referenced the conjoined twins in several ways, such as by wearing a pink sash connecting him to another man onstage at a New Year’s Eve party; in “Personal Habits of the Siamese Twins” (1869), republished as “The Siamese Twins” in his 1875 collection Sketches New and Old, Twain provides an account of the Bunkers’ lives, including both true and outlandish anecdotes.

Although Chang and Eng Bunker were viewed as curiosities due to their unique physical condition of being conjoined, they led remarkably normal lives and even managed to achieve what many would consider the epitome of a normal lifestyle: marriage and children. Chang and Eng each married separate women, Adelaide and Sarah Yates, respectively, in 1843. Together, they raised a total of 21 children between them. Despite their physical connection, they maintained separate households, alternating three days at each residence.

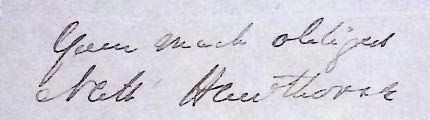

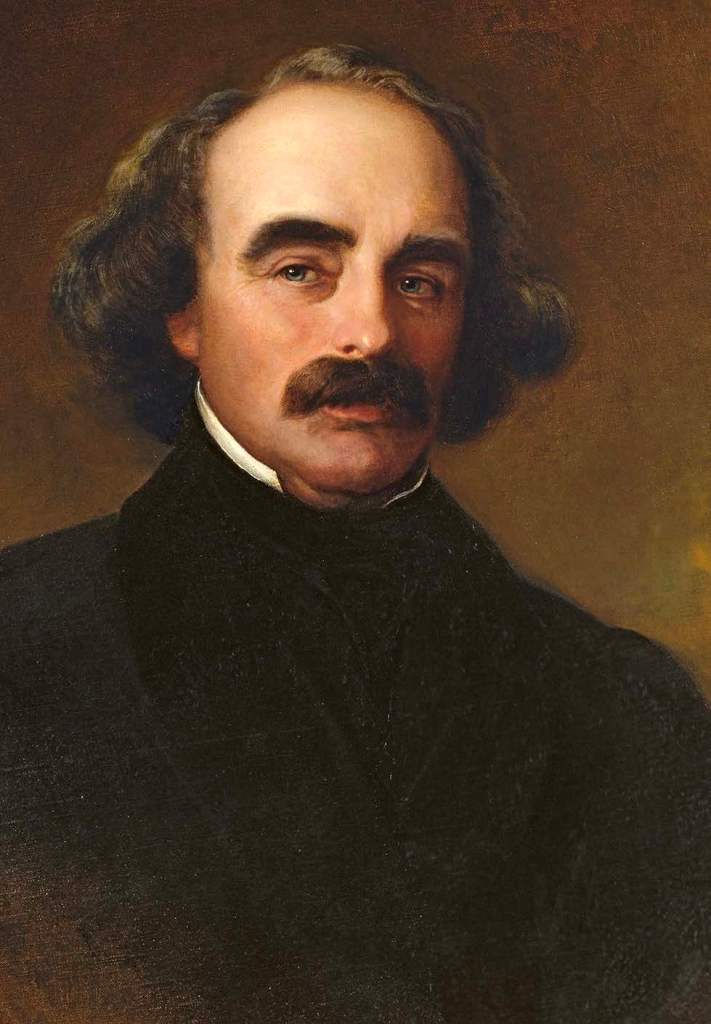

A third figure within the entertainment industry and whose autograph would have been collected by many is Nathaniel Hawthorne’s. Nathaniel Hawthorne was born in Massachusetts in 1804. He was an American novelist and short story writer related to John Hathorne who was one of the judges who oversaw the Salem witch trials. He is best known for his novel “The Scarlet Letter,” which explores themes of sin, guilt, and redemption in Puritan New England. Hawthorne’s works are characterized by their psychological depth, moral ambiguity, and exploration of the human condition. His writing style often blends elements of romanticism with realism, making him a pivotal figure in American literature. Hawthorne’s contributions to literature have had a lasting impact, influencing generations of writers and shaping the development of the American literary tradition.

11.134. Item 134: Autograph from Nathaniel Hawthorne, no date.

Portrait Gallery

Nathaniel Hawthorne would become so well known that he would be receiving letters from various people. A letter from 1854 provides a sense of how he would discuss other literature with individuals.

Library, Archives & Manuscripts

Transcription: My Dear Sir, I return you a large package of books, which ought to have been sent back long ago; and with them, I send an American Book, “Up-Country Letters”-which I beg you to read & hope you will like. It would gratify me much if you would talk about it, or write about it, and get it into some degree of notice in this country. England, within two or three years past, has read & praised a hundred American books that do not deserve it half so well; but I

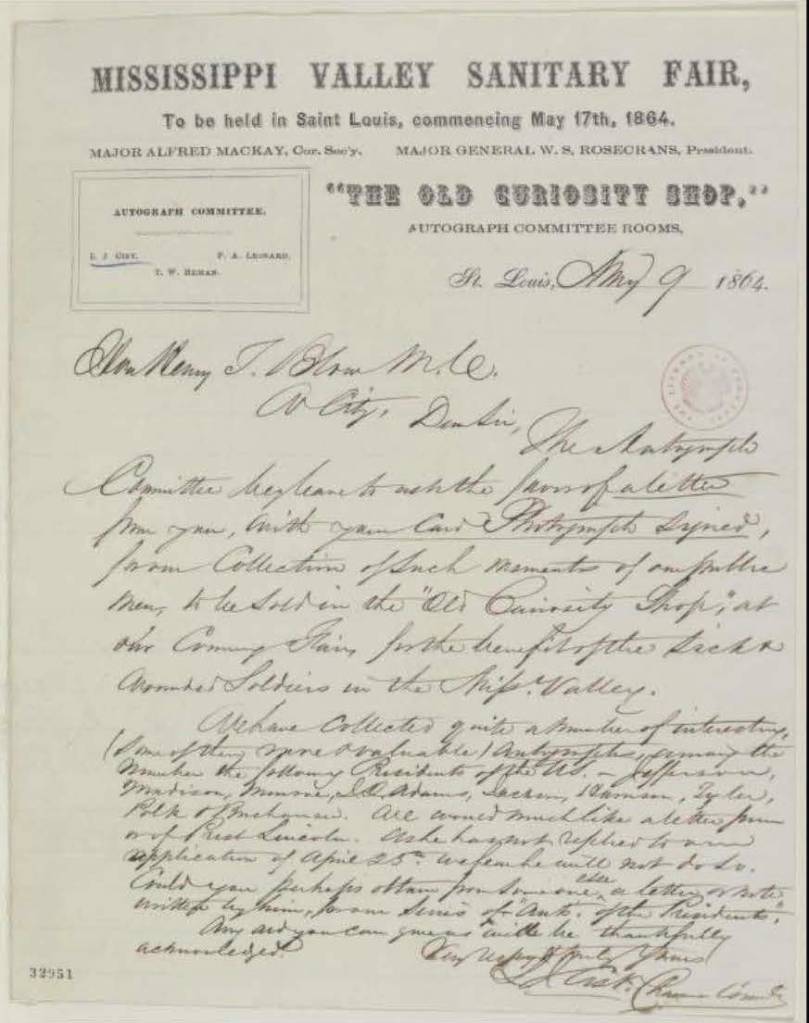

Autographs were also collected as fundraising efforts for the United States Sanitary Commission. The United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) was a civilian organization established during the American Civil War, with prominent figures Frederick Law Olmsted and Henry Whitney Bellows, to provide medical and sanitary assistance to Union soldiers. Founded in 1861, the commission operated as a relief agency, coordinating the efforts of thousands of volunteers, both women and men, who worked tirelessly to improve the often dire conditions faced by soldiers in the field.

Many of the USSC’s appeals to the public included letters distributed through newspapers, community meetings, or other forms of communication. To further give credibility to their appeals, the commission sought out signatures from prominent individuals such as politicians, community leaders, or celebrities. These signatures would be prominently displayed on the letter to encourage others to become involved with the Commission. Autographs of notable figures, especially military leaders and political figures, were often auctioned off or sold at different events to raise funds for the Sanitary Commission.

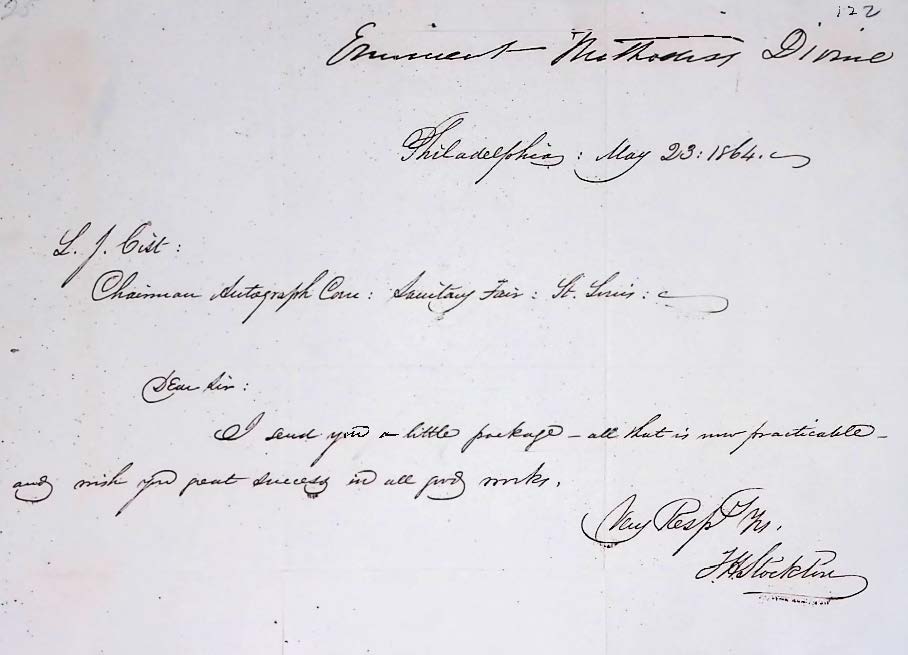

One such example of autograph collection for the benefit of the Sanitary Commission comes from a letter written by John Stockton, a minister, composer, and musician, to Lewis Jacob Cist, the Chairman of the Autograph Commission under the Sanitary Fair, on May 23, 1864.

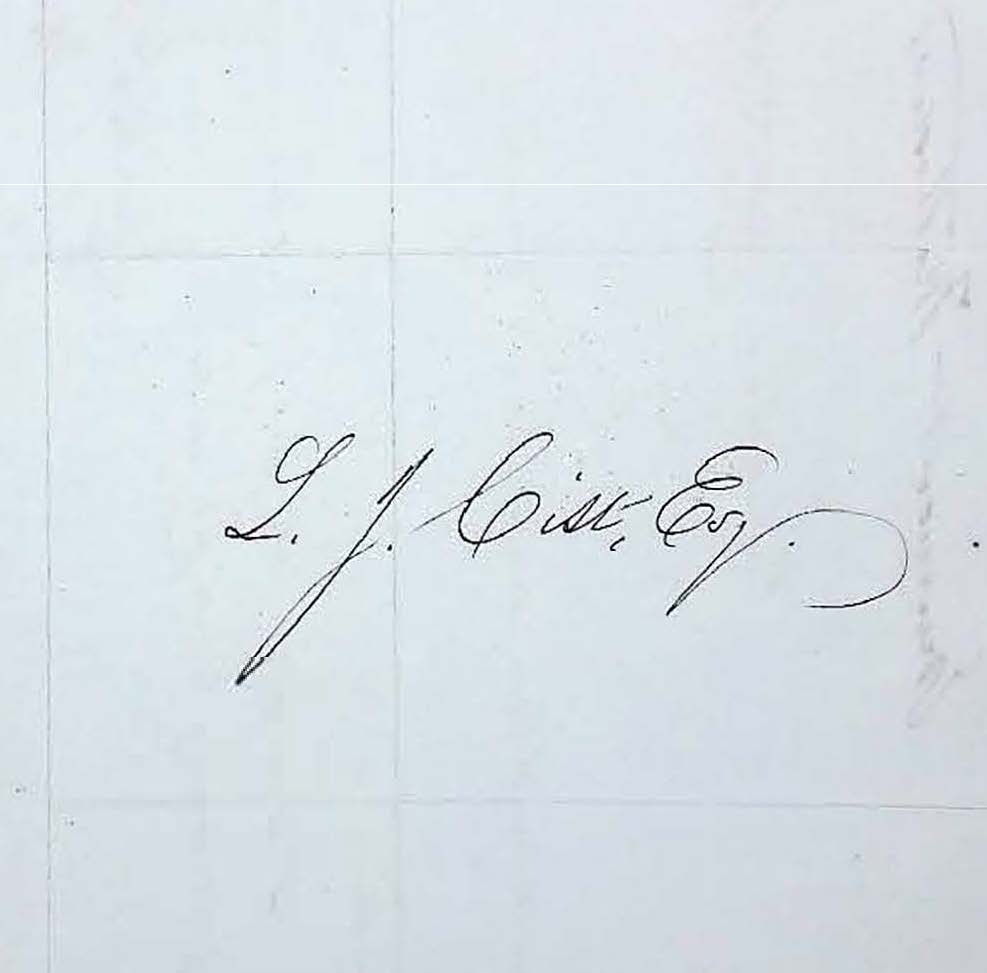

ACD May 2024 via The Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore

Aside from his involvement in Sanitary Fairs, Cist was a banker, historian, and poet. He was known for his autograph collection, likely leading him to the position in the commission. Throughout his life, Cist donated both autographs and artifacts to Sanitary Fairs in the west (C.F. Vent & Company, “History of the Great Western Sanitary Fair,” pp. 418-464) Cist’s autographs were sold to Bangs & Co., an auction house based in New York City (De Simone Company Booksellers, “Education & Miscellaneous Americana”).

The letter from John H. Stockton to Lewis J. Cist reveals the autograph collecting efforts for fundraising purposes by the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC). Cist was the Chairman of the Autograph Committee for the Sanitary Fair in St. Louis, where the autographs were auctioned off at the fair to support the USSC’s humanitarian efforts.

11.76. Item 76: Letter from J. H. Stockton to L. J. Cist, 1864 May 23.

Chairman Autograph Com: Sanitary Fair: St. Louis:

Dear sir:

I send you a little package-all that is now practicable- and wish you great success in all good works.

Very Respectfully yours

J. H. Stockton”

Stockton’s “little package” contains autographs or items related to the fundraising efforts. By expressing his wishes for “great success in all good works,” Stockton is not only conveying his support for the fundraising endeavors but also endorsing the broader mission of the USSC in providing medical and sanitary assistance to Union soldiers. This letter demonstrates the collaborative effort among individuals like Stockton and Cist, who understood the popularity of autograph collection for popular figures, and used it to the advantage of both their popularity and the Sanitary Commission’s funding.

In another letter from Cist to Henry T. Blow, politician and former Minister Resident to Venezuela under Abraham Lincoln, in 1864, Cist collected autographs for the St. Louis Sanitary Fair.

“Dear Sir,

The Autograph Committee beg leave to ask the favor of a letter from you, with your Card Photograph Signed, for our Collection of Such mementos of our public men, to be sold in the “Old Curiosity Shop”, at our Coming Fair for the benefit of the Sick & wounded Soldiers in the Missi Valley.

We have collected quite a number of interesting, (some of them rare & valuable) Autographs, among the number the following Presidents of the U S. — Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, J. Q. Adams, Jackson, Harrison, Tyler, Polk & Buchanan. We would much like a letter from or of Prest Lincoln. As he has not replied to our application of April 25th we fear he will not do so. Could you perhaps obtain from someone else a letter or note written by him, for our Series of “Aut’s of the Presidents”.

Any aid you can give us will be thankfully acknowledged. Very respy & truly Yours”

Within the following letter, Cist requests a letter and a card photograph signed by Abraham Lincoln, which would be included in the collection of mementos from public figures (such as Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, John Quincy Adams, and more) sold at the Sanitary Fair. It is evident through Cist’s communication that autographs held extreme importance to the public, drawing them in to purchase for their own collections, therefore contributing to the Sanitary Commission’s mission. Therefore, acquiring an autograph from President Lincoln would draw attention from all over the country, as they had the opportunity to own an autograph from a living president at that time.

Following the letter to Blow, Cist finalized his collection of autographs and photographs from different presidents, vice presidents, cabinet members, and representatives, contributing the exhibition to the Mississippi Valley Sanitary Fair. The Daily Countersign in 1864 appraised Cist’s collection to be worth ten thousand dollars, which is worth around 198,938 dollars today. Cist’s commitment to collecting autographs for the commission allowed him to explore his interests in the hobby, finding an application for it to appeal to the general public. His letters served to network and connect with other prominent American figures in exchange for their signatures as advertisements for the fair. Additionally, the success of these Sanitary Commissions show the popularity of the hobby in the mid-nineteenth century.

Lewis Cist’s hobby turned strategy paved the way for autograph collection to develop even more, transitioning into a profitable business model rather than a collection. As the Sanitary Commissions placed values on the autographs, the public became more and more interested in the idea of holding autographs from prominent American figures. Autograph collection was a market earlier in the nineteenth century, as auctioneers sold both collections and single autographs publicly in Europe. Later in the century, few autograph and manuscript shops began opening in New York City and dominating the market to respond to dwindling numbers of first generation collectors (Raab Collection, “The History of Autographs: The Lure of Collecting”).

We can see how businesses presented, preserved, and valued their autographs with an envelope that enclosed a previously mentioned letter [L.E. Parsons to William Jessup].

11.63. Item 63: Envelope from L.E. Parsons to Judge [William] Jessup, 1835 December 3.

Hamilton

Autographs

515 MADISON AVE., NEW YORK 22. N.Y.

Fine Autographs of Interest and Importance””

The letter from Parsons to William Jessup is stored in a folder from Charles Hamilton’s Autographs, a business run by notorious handwriting expert Charles Hamilton. Charles Hamilton was a handwriting expert and dealer based in New York City, famously known for his ability to discern the authenticity of documents with precision and insight, noting that he could “spot a forgery from across a room” (JG Limited, “Pioneer Autograph Dealer Charles Hamilton’s Original Red Wax Authentication Seal”). Additionally, Hamilton published numerous works on his experiences collecting autographs or historical information with his autographs, such as Leaders & Personalities of the Third Reich: Their Biographies, Portraits, and Autographs and The Signature of America: A Fresh Look at Famous Handwriting.

ACD May 2024 via JG Limited

The envelope from Charles Hamilton serves as a representation of the commercial aspect of autograph collecting during the 19th century. The inscription on the envelope highlights Hamilton’s role as a respected dealer and authenticator of these autographs. His reputation as a dealer allowed him to mentor others in autograph collection and authentication, ensuring other people could spot forgeries and ensure that people could access true, historically significant documents (Nickell, Real or Fake: Studies in Authentication, pp. 102-103).

Hamilton’s envelope for his business also illustrates the market demand for rare and noteworthy autographs throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as well as how Hamilton and other autograph businesses capitalized on it by establishing businesses dedicated to sourcing and selling these items. Another example of prominent autograph collectors is Walter R. Benjamin, a New York-based rare book and manuscript dealer, which the Online Archive of California houses a significant portion of his collection of documents, correspondence, and manuscripts from individuals.

This envelope suggests that individuals like Hamilton recognized the market demand for rare and noteworthy autographs and capitalized on it by establishing businesses dedicated to sourcing and selling these items. As such, the envelope serves as an artifact of the thriving autograph trade during the 19th century, illustrating how autograph collecting evolved from a hobby into a commercial enterprise driven by the interests of collectors looking to enhance their collections with prized signatures of historical figures.

Hamilton and other collectors’ insight into their collections and authenticity raises the question of the possibility of falsified autographs circulating during the early twentieth century. However, it actually reveals the meticulous nature of authenticating autographs and ensuring that true historical documents are preserved. Based upon accounts from other historians and autograph connoisseurs, detecting a valid autograph is an art form. For example, becoming ingrained in autographs means knowing how different figures wrote, from their strokes to their signatures. For example, Abraham Lincoln never signed his letters as “Abe” (Rabb, “The Fraught and Risky Business of Spotting a Historical Fake”).

As people like Hamilton explored their interests in history through autograph collections, they gained great knowledge of how these people wrote, the language they used, the pens, the inks, and so much more. Additionally, these people became well aware of how others used the appeal of owning a historical figure’s documents to sell fakes (Rabb, “The Fraught and Risky Business of Spotting a Historical Fake”). Today, collectors publish detailed tips on how to authenticate documents and ensure what one is encountering is real.

The hobby of autograph collection lives on today. The practice has branched into different niches, the most well known being concerning the entertainment and music industries. We regard celebrity autographs highly, even selling memorabilia or signed objects relating to these celebrities. For example, AutographPros currently lists a signed 18-string double neck guitar signed by founder and guitarist of Led Zeppelin, Jimmy Page. Although celebrities’ autographs may overshadow the appeal of historical autographs and manuscripts, the practice still lives on. Numerous businesses have listings of various figures, both American and international historical figures like politicians, authors, lawyers, and more, which closely resembles the subseries in our collection.

Based on the Autographs subseries of the American Figures Collection, it is evident that the following highlighted entries follow the trajectory of the history of autograph collection in the United States. These autographs range from late eighteenth century Revolutionary America, to the latter half of the nineteenth century, as well as connections closer to today. The manuscripts reveal the consistent importance of politicians, lawyers, and entertainers to the public throughout our history, as well as providing fascinating parallels to how we regard autographs and signatures today. Understanding the history of autograph collection through the following subseries provides researchers with a better, overarching narrative of the hobby (primarily during the nineteenth century) and its significance over time.

Aside from autograph collection, some find it pertinent to collect art of prominent American figures. Although autographs or letters reveal personal details and unearth new information about important historical events, some regard collecting art as an interdisciplinary look into American history, which can be seen in the Art/Sketches portion of the American Figures collection.

The third subseries within this collection is a short collection with different sketches ranging across the 19th century, with one item unknown. These drawings reveal the interdisciplinary usages of art for literature, politics, and science. However, the most prominent drawings come from caricaturist and cartoonist Thomas Nast and entomologist Herman Strecker. The different works from these two highlight the various usages of scientific illustrations and political cartoons for different, yet intellectually stimulating purposes. From engaging in political criticism to scientific classifications, both artists create meaningful art that we can look at and analyze today.

Thomas Nast (1840-1902) was a German-American caricaturist and editorial cartoonist. He is revered as the “father of the American cartoon.” Nast moved to New York at six years old, where his father introduced him to the arts through his work in a theater orchestra. This predisposition to the arts combined with the growing magazine industry in the United States during the 1850s and 1860s. New York City specifically housed great wealth within magazines. As Nast came of age, media in New York was full of close-knit circles of all different kinds of writers and illustrators, which gave him the in to work as an illustrator for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Magazine at just fifteen years old in 1855 (Keller, “The World of Thomas Nast”).

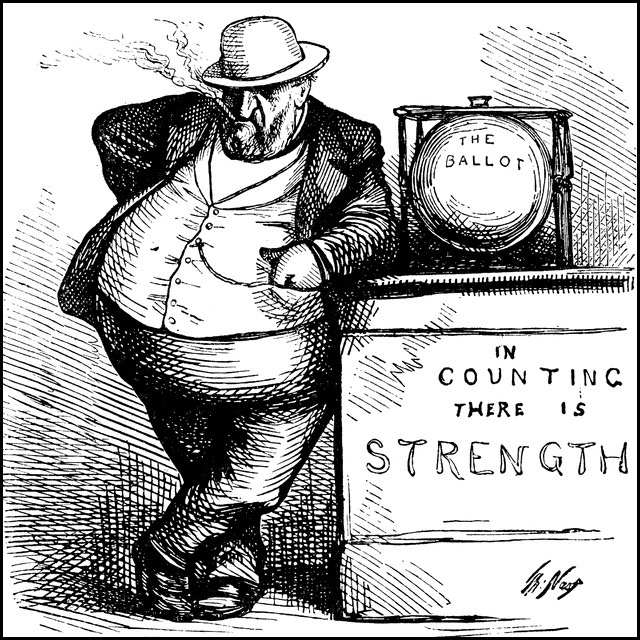

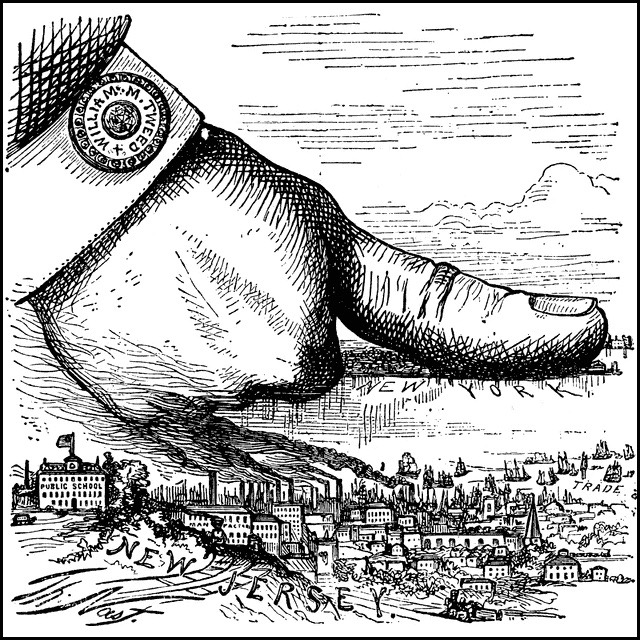

Although Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Magazine did not publish many of his works, Nast’s early ventures within the publishing industry gave him the tools and connections to continue working for other publications like Harper’s Weekly. His craft gained traction, and Nast soon became one of the most influential cartoonists of the nineteenth century (Florida Center for Instructional Technology, Thomas Nast).

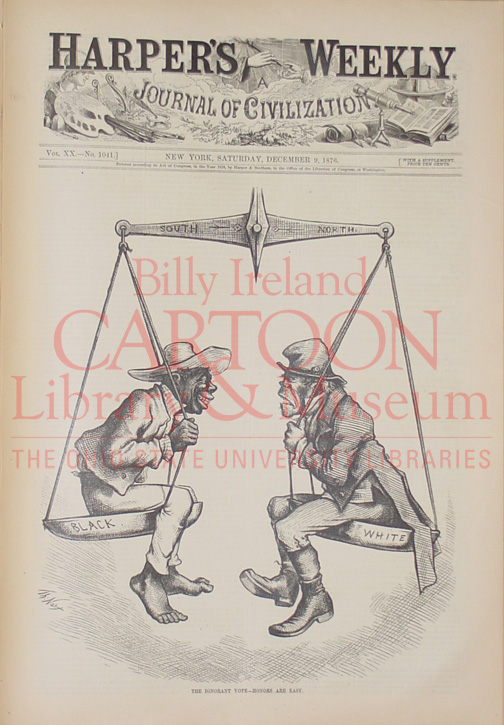

Nast’s talent became nationally recognized during the Civil War, as his cartoons upheld views supporting the Union. His pieces criticized the Democratic party and its platform to uphold slavery in the United States, some through the deceptive guise of support. Despite Nast’s anti-Democrat sentiments during the Civil War, his attitudes shifted shortly after as African-Americans exercised their new rights and attained public positions. Nast began to critique the Republican party and adopt negative stereotypical imagery when depicting African-Americans (Keller, “The World of Thomas Nast”).

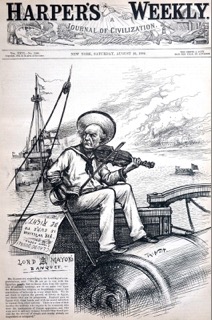

Harpers Weekly, December 9, 1876 cover

ACD April 2024 via Ohio State University Libraries

Nast was most well known for his political cartoons critiquing William “Boss” Tweed and Tammany Hall political machine. Harper’s Weekly ran numerous cartoons of Nast, attacking Tweed and his political ring for their illegal activities. These cartoons sparked anxiety in Tweed because his illiterate constituents would still be able to interpret the meaning of these cartoons. The cartoons all adopted a similar style and attest to the artistic skills of Nast seen in his cartoon within the collection.

ACD April 2024 via Florida Center for Instructional Technology

ACD April 2024 via Florida Center for Instructional Technology

Nast’s cartoons do not end with focus on domestic politics. Before the Civil War, Nast traveled abroad to England and Italy to report for the New York Illustrated News and London Illustrated News. He also delved into illustrating cartoons on foreign affairs. Specifically, Nast covered the Anglo-Egyptian War of 1882. Britain and France maintained interest in Egypt since the late 18th century, finally assuming control of all finances in 1879 (The Highlanders’ Museum, “The Anglo-Egyptian War”). However, the most notable revolt, generating immense tension between the Egyptians and the British, was the small “Urabi Rebellion” of September 1881, assuming a nationalist message of “Egyptians for Egypt.” Although this rebellion was started by only four within the Egyptian forces, this caused great anxiety for Britain and its security over the Suez Canal (Al-Sayyid-Marsot, “The British Occupation of Egypt from 1882,” in The Oxford History of the British Empire: The Nineteenth Century).

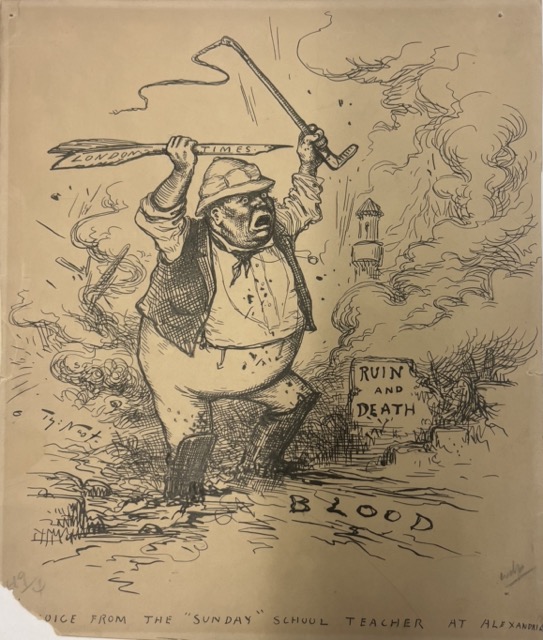

11.101 Item 101: Drawing by Thomas Nast, titled “Voice From The “Sunday” School Teacher at Alexandria,” late 19th century.

The revolt within the Egyptian army led to the Bombardment of Alexandria. A British fleet began a bombardment of the city on June 11, 1882. Tensions leading up to the revolt and bombardment fell along religious lines, as Egyptians allegedly spoke of how Christians (the Europeans) would die and that they should prepare (Chamberlain, “The Alexandria Massacre of 11 June 1882 and the British Occupation of Egypt”). The bombardment resulted in significant bloodshed, with 50 Europeans and 170 Egyptian casualties, and the British assumed control over Egypt in months following (Al-Sayyid-Marsot, “The British Occupation of Egypt from 1882,” in The Oxford History of the British Empire: The Nineteenth Century).

Nast depicted these tensions between Egyptians and Christians in his cartoon captioned “Voice from the ‘Sunday’ School Teacher At Alexandria.” He adopts a critical stance against the British, following the art style typically used in his Tweed critiques. He shows a British soldier, which can be inferred when comparing outfits to paintings and photos of soldiers in Egypt, especially their hats, as seen in paintings depicting the following Battle of Tel-el-Kebir.

ACD April 2024 via British Battles

The soldier holds his riding crop and an arrow labeled as “The London Times” up high, standing in “blood” bringing “ruin and death” upon Alexandria. There is minimal information as to why the London Times is highlighted in this cartoon, but it is likely that Nast was critical of the newspaper’s coverage of the event and coverage of the religious tensions in Egypt. Although, typically, Christians would likely condemn violence in such a manner for this conflict, Nast displays the irony of said beliefs because of the mass casualties during the Bombardment of Alexandria. Essentially, the deaths of both Europeans and Egyptians are not necessarily Christian in nature.

However, this is not the only critical cartoon of Nast’s concerning the Anglo-Egyptian War. The August 26, 1882 edition of Harper’s Weekly features Nast’s depiction of Prime Minister William Gladstone sitting on a British ship, playing an opera about highwayman Claude Duval on his fiddle, alluding that he is to be right about his decisions regarding the Anglo-Egyptian Conflict. Although Gladstone sits and plays music, the background shows Alexandria burning following the Bombardment.

Harper’s Weekly, August 26, 1882.

ACD April 2024 via All Things Brooklyn Listing

The caption reads the following: “MR. GLADSTONE, responding to the Lord Mayor’s congratulations, said: ‘We do not go to war with the Egyptian people, but to rescue them from the oppression of military tyranny… England goes to Egypt with clean hands, and with no secret intention to conceal from other nations…” The juxtaposition of Gladstone’s reassuring words about British occupation in Alexandria with a scene of destruction as Gladstone happily plays music to himself reveals Nast’s discontent with the European strategy in the Anglo-Egyptian Conflict.

Although Thomas Nast is revered for his artistic contributions to political cartoons, especially targeted at United States politics, he was not confined to the American sphere. His item within the collection reveals another layer of his political beliefs and artistic talents as he critiqued Britain’s actions and involvement in Northeast Africa.

Herman Strecker and Entomology

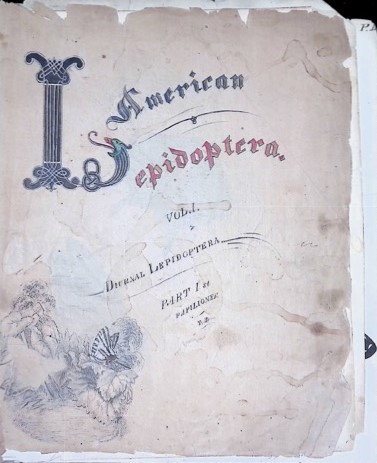

With the rise of different forms of scientific illustration in the Nineteenth century, comes the illustrations of avid entomologist Herman Strecker. Ferdinand Heinrich Herman Strecker (1836-1901) is most famously known for his specialization in butterflies and moths, also known as lepidoptera. Strecker, a Pennsylvania native, was an architect, designer, sculptor, and traveler with an avid interest in collecting specimens of lepidoptera. He is most famously known for his entomological publications full of illustrations (Weiss, “An Interview with Herman Strecker in 1887”).

I find it interesting but also important to highlight the background of entomology during the nineteenth century before looking at Strecker’s works within the collection. Entomology is the study of insects and their relationships with the world around them, such as humans, their environment, and other animals. Scientists cite entomology as vital to researching food production, pharmaceuticals, among other phenomena in the various fields of science (Washington State University Department of Entomology).

From the mid-eighteenth to the late nineteenth century, entomology was not a fleshed out and professional study. Many “entomologists” were hobbyists with other professions. These people worked in museums, schools, shops, as doctors, lawyers, and many more professions. The study of entomology did not consist of a majority of paid, professional researchers or academics until the twentieth century (Elias, “A Brief History of the Changing Occupations and Demographics of Coleopterists from the 18th Through the 20th Century”). It is not surprising that Strecker held a different occupation rather than solely focusing on entomology as a result of the field at the time being relatively small.

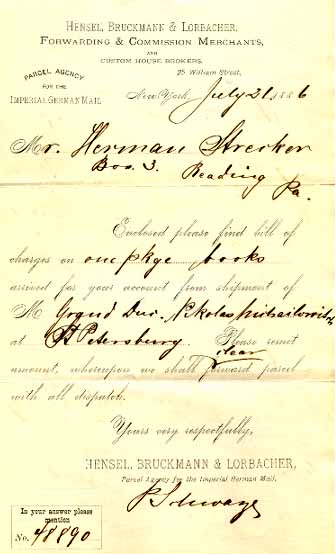

Despite entomology being more of a “niche” than a well-developed branch of scientific research, it did not stop Strecker from actively engaging with other hobbyists and accumulating a large collection of specimens. Strecker began his collection of butterflies and moths as a teenager as well as writing to other entomologists around the world. Most notably, Strecker frequently corresponded with Grand Duke Nicholas of Russia, exchanging books, specimens, or information about their interests (Field Museum, Herman Strecker Collection).

ACD April 2024 via The Field Museum

Herman Strecker’s interests also manifested in his sketches, some of which are found in our collection. Strecker combined his artistic skills with his passion for moths and butterflies through his sketches, which he eventually published in multiple books. Some of these books highlight instructions for collection, breeding, classifying, or packing different specimens, while others include descriptions or how different species interact with their environment (Biodiversity Heritage Library). Strecker’s drawings, some of which are incomplete, show his attention to detail and passion for lepidoptera and entomology as a whole.

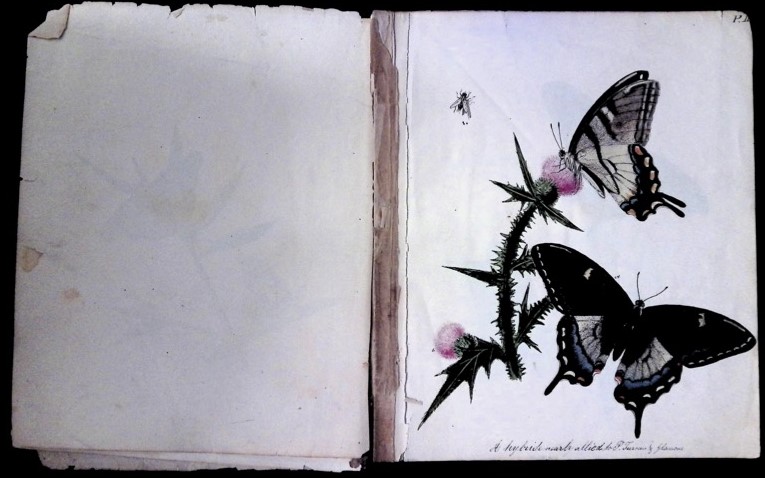

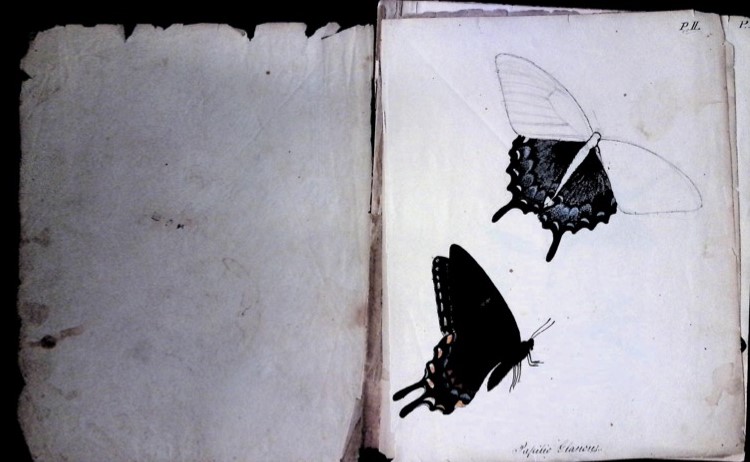

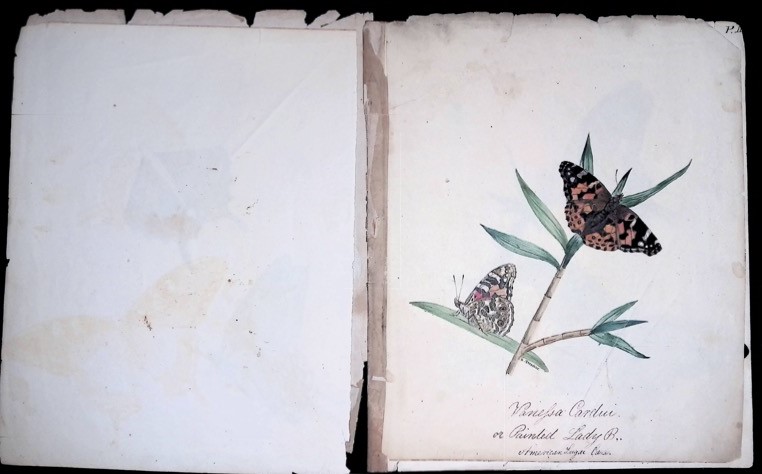

The following selections from Strecker’s booklet display different species of butterflies. For example, one page highlights the Vanessa Cardue or Painted Lady B., as well as showing the plant which it may be found around.

11.103. Item 103: Drawings from American Lepidoptera, volume I: Diurnal Lepidoptera. Part I: Papilones. By Herman Strecker, prior to 1872

I find it fascinating how Strecker shares his knowledge in these drafted drawings, even if it is not specifically to highlight each insect’s interaction with nature. Strecker is not including pages of research and language to accompany the drawings. Still, Strecker displays these insects in their natural habitats and interacts with different plants and insects. Overall, he is making use of his artistic gift to display his love for entomology. The following booklet in the collection is seen in his different works, such as both editions of Lepidoptera, Rhopalocera and Heterocerus, Indigenous and Exotic; with Descriptions and Colored Illustrations.

The following selections are just a sliver of the rich knowledge the collection provides for researchers and scholars. Altogether, processing and researching the American Figures collection provided us an excellent opportunity to strengthen our knowledge of American history and dive deeper into major eras in early America. Being able to research and learn about politicians, authors, and activists we had never heard of made coming back to the collection each day more and more exciting and fulfilling. Being able to contribute to the field of American history through the collection has been extremely intellectually rewarding.

As such, we think this collection will be useful for researchers interested in investigating political figures and activists across the nineteenth century, specifically their networking with one another and maintaining loyalty to their causes. Researchers can construct new theses and historical narratives concerning nineteenth century America through such letters. Additionally, other subseries of the collection provide researchers a basis to comprise additional sources for various American figures, or continue dissecting the practice of autograph collection and its history moving towards the present.

This collection reveals the variety of topics which American figures deliberated across three centuries, all transitioning with American history. From the Revolutionary Era, to Antebellum America, leading into the early twentieth century, you can find an array of knowledge that demonstrates how citizens rise up to address the political causes that inspire them. In a pessimistic sense, we can say the United States has a turbulent history regarding civil rights and liberties. However, through this collection, you can place yourself within the minds of American figures, directly understanding their actions and movements to advance their progressive convictions.