Wilkes University Archives is excited to announce that thanks to Emma Broda, a Sophomore History major Women’s and Gender Studies minor, the Helen Farr Sloan Collection of Political Cartoons, 1802-1950, is processed and digitized! Emma is a member of the Honors Program and a News staff writer for the Beacon. Following her time at Wilkes, Emma is interested in continuing her studies in history, specifically interested in American history.

The finding aid for the collection along with digitized cartoons can be found here. The finding aid and blog post have been edited and supervised by Suzanna Calev, Wilkes University Archivist. Below are Emma’s reflections.

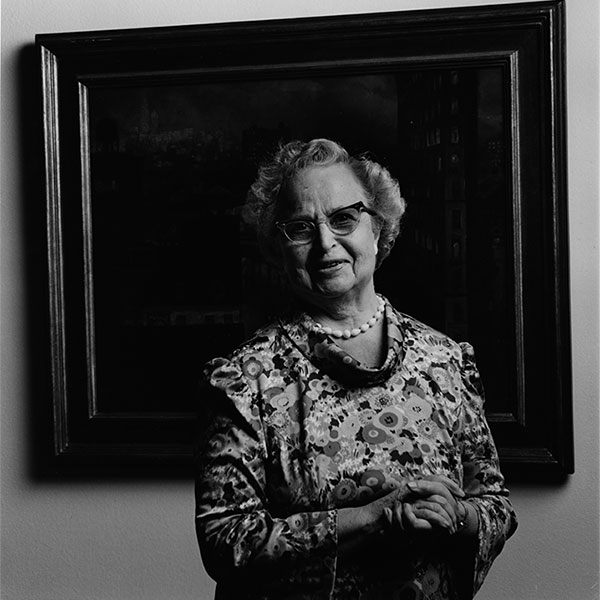

The Helen Farr Sloan’s collection of political cartoons contains a wide variety of prints including political cartoons, caricatures, and illustrations from different magazines and publications. The collection was donated to Wilkes University by Helen Farr Sloan, an accomplished artist and patron of the arts. Sloan began studying art at a young age and dedicated her life to creating, teaching, and donating art. She became a member of the Arts Student League in New York at sixteen where she would meet John Sloan, who would later become her husband. She also worked with the Santa Fe art colony, was head of the art department of the Nightingale-Bamford School, and co-wrote a book with John.

After her husband’s passing, Sloan donated much of his art as well as other pieces to institutions such as the Smithsonian Institution, the New York Historical Society, the National Gallery of Art, the Delaware Art Museum, and the Sordoni Art Gallery. She had been appointed a member of the Sordoni Advisory Art Commission where she became acquainted with Wilkes University and eventually donated many collections, including this collection of political cartoons.

Delaware Art Museum; ACD March 2024

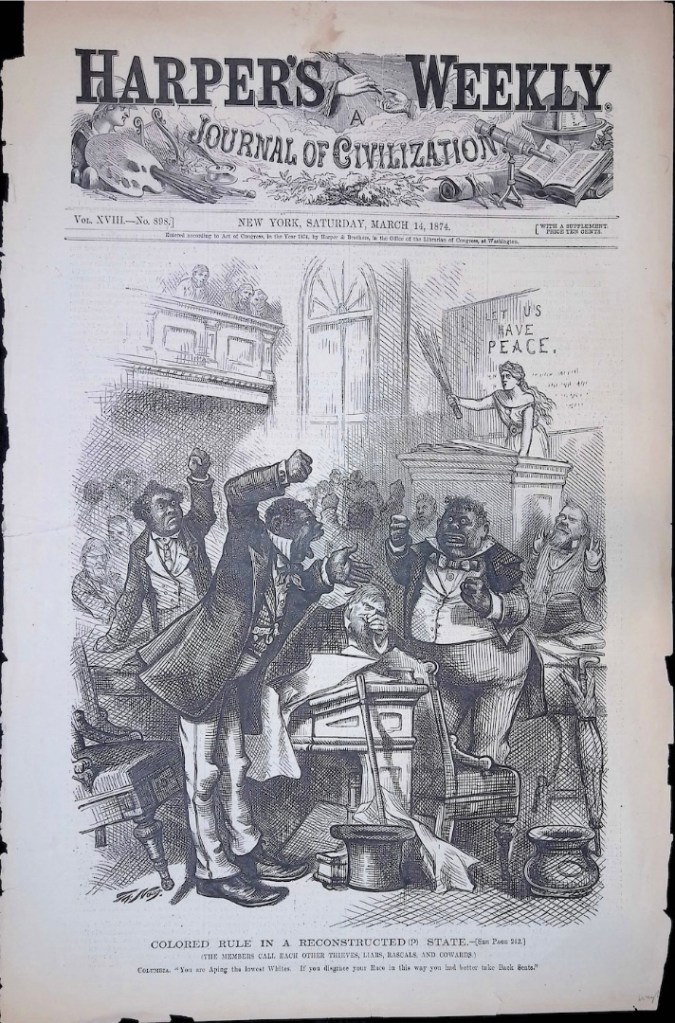

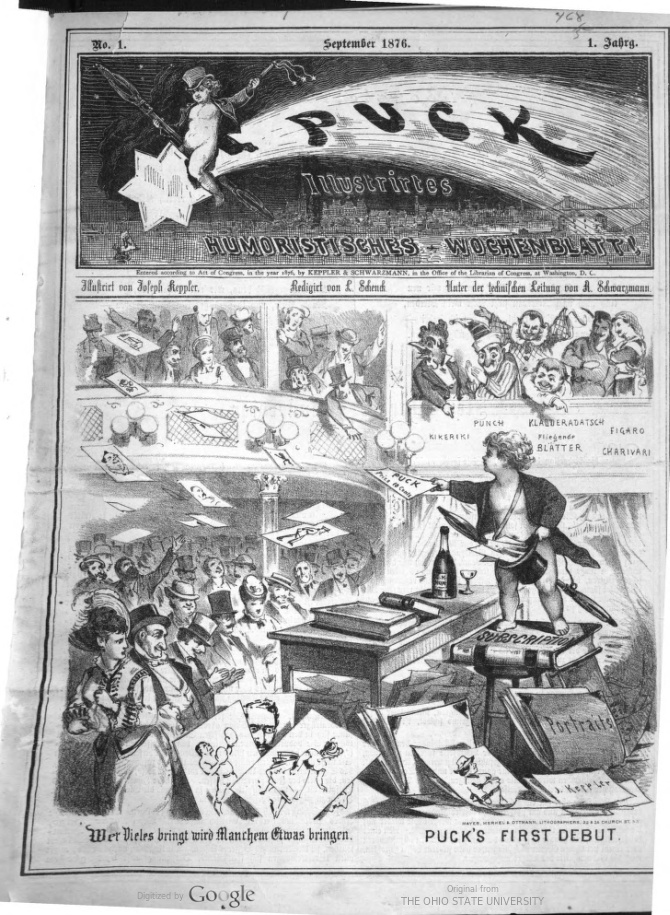

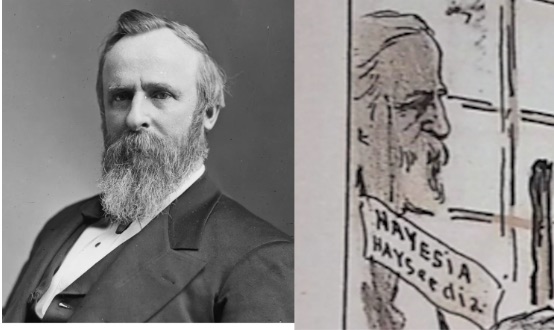

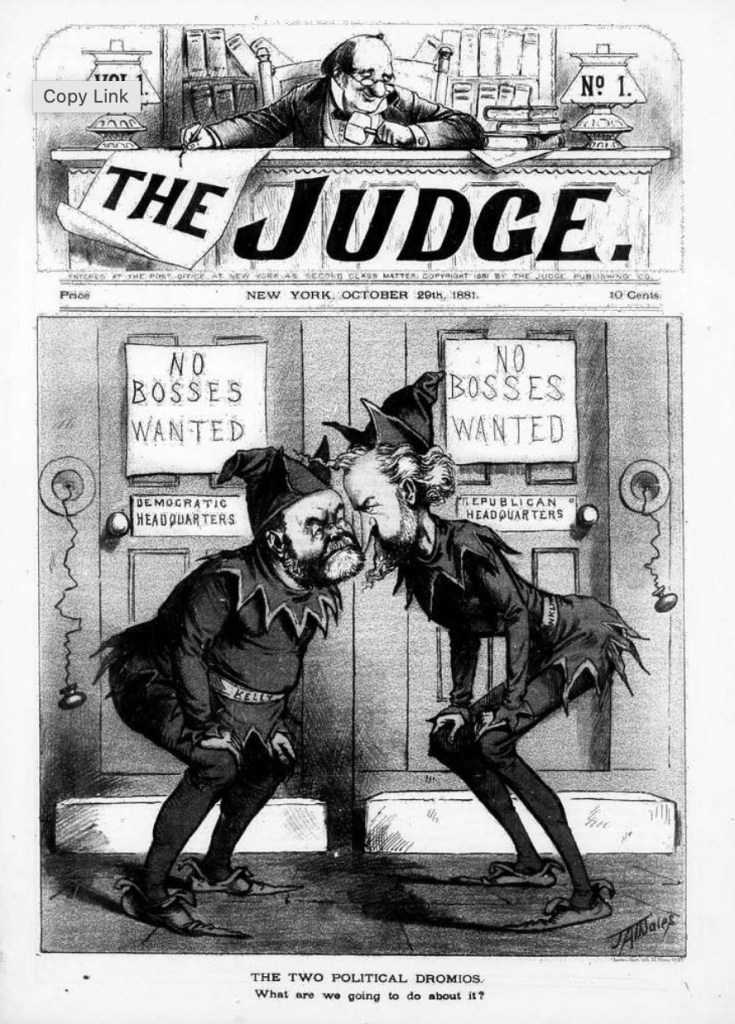

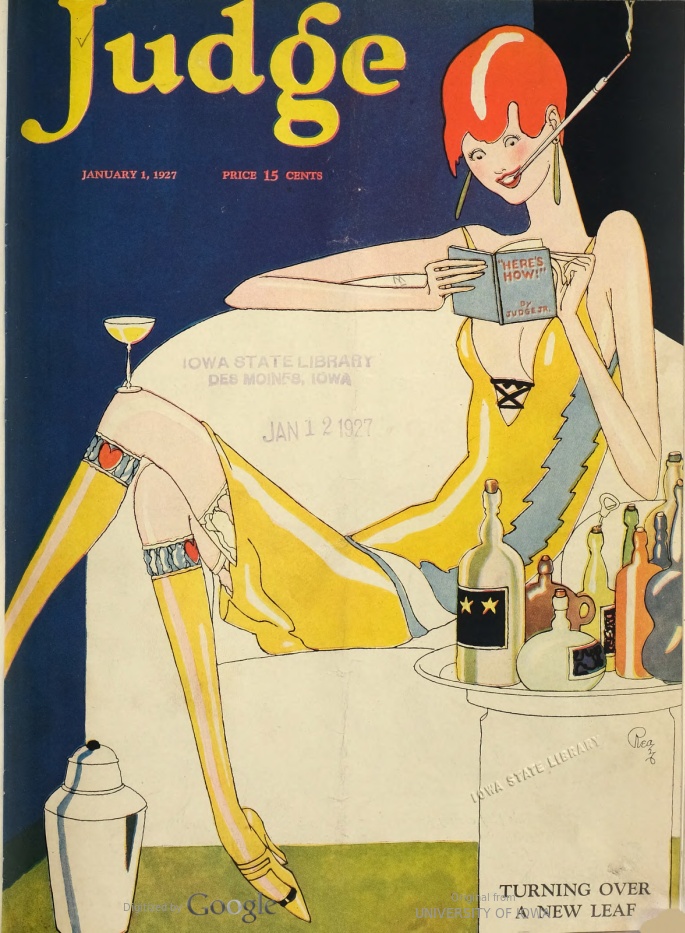

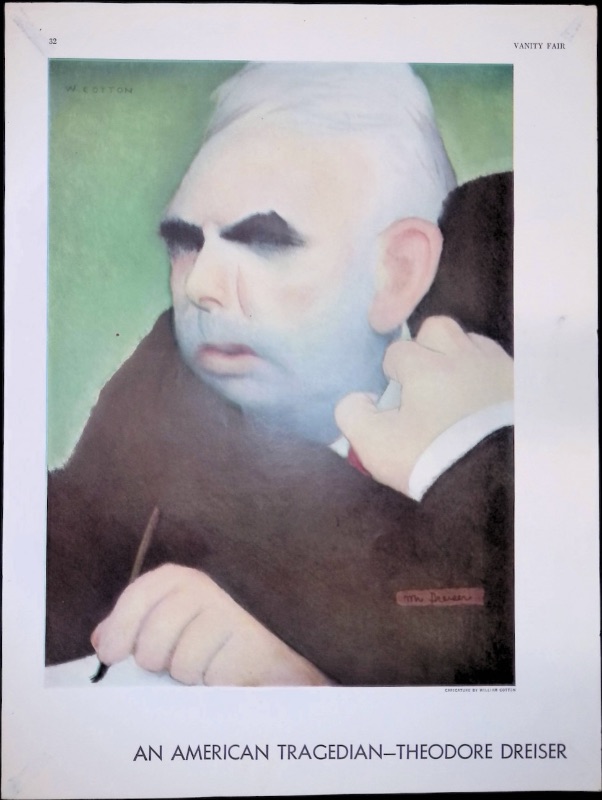

The materials come from pages of magazines such as Puck, Judge, Vanity Fair, Vanity Fair, Harper’s Weekly, Gil Blas, Le Charivari, Truth, The New Yorker, The Illustrated London News, The New York Herald, and The Sun. There are also pages from books such as Les Gens de Paris and prints from other publications such as Treager’s Black Jokes, and publishers such as S.W. Fores, Currier & Ives, and J. Sidebotham. There are also prints from the artist Thomas Rowlandson. The collection is split into Series I: Puck Magazine Prints, 1879-1899; Series II: Judge Magazine Prints, 1882-1900; Series III: Vanity Fair Magazine Prints, 1869-1931; Series IV: Harper’s Weekly Magazine Prints, 1868-1880; and Series V: Other historic magazine prints, 1802-1950. Below is a collage of some of the incredible covers from this vast collection of political cartoons.

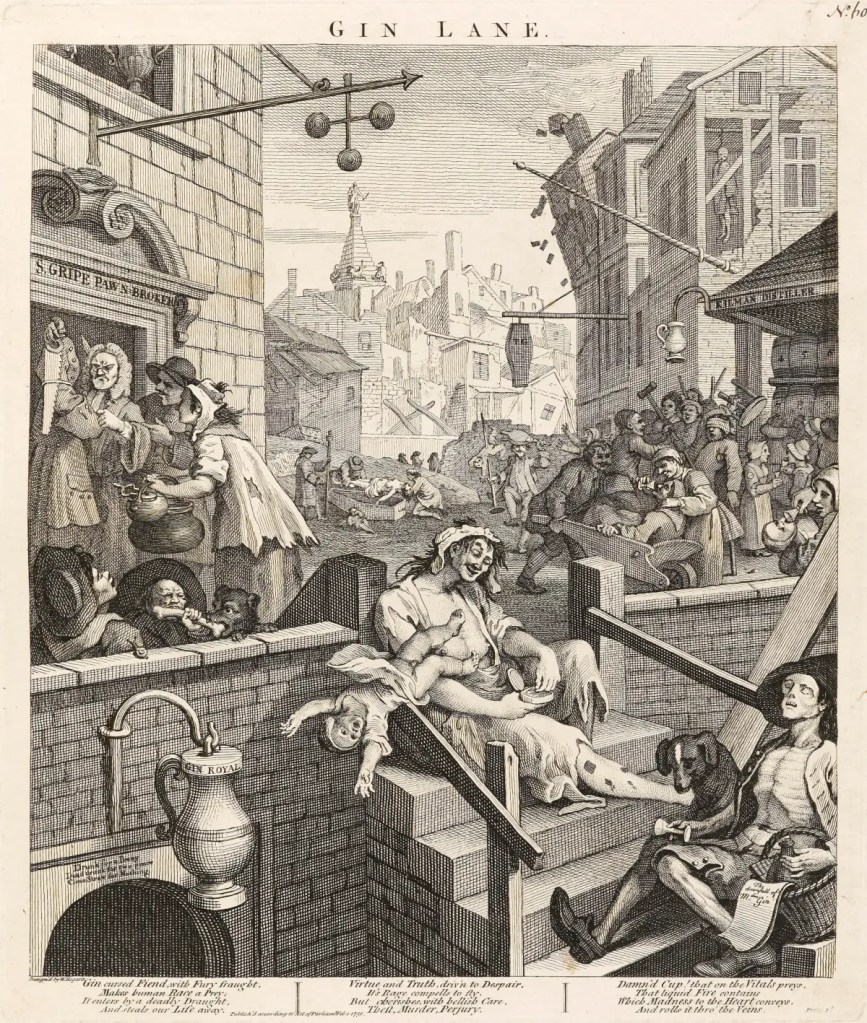

Although these political cartoons were published during the Gilded Age, or what historians considered to be the “golden age” of political cartoons, the history of political cartoons and satirical caricature goes back much further. It is common when looking at historic political cartoons and satire, that historians place the “beginning” of this style of art– a drawing (often including caricature) made for the purpose of conveying editorial commentary on politics, politicians, and current events–in the eighteenth century with people like William Hogarth and James Gillray who both get credited as being the “fathers” of political caricature. While I do believe that they heavily developed what would become the more modern style of caricature seen in the “golden age,” the general theme of art to comment on current events, and speak to your audience can be traced further back in history before Hogarth and Gillray.

The concept of caricature dates back to Leonardo da Vinci, but the use of it for political and social commentary seems to appear during the era prior to the Protestant Reformation and throughout the Reformation. During this time period, there were conflicts in laws surrounding freedoms of speech and printing. The Catholic Church had feared people speaking publicly against Church officials and had sought to prevent it, which led to more tensions between the Catholic Church and Proto-Protestants. It was also around this time that some of the earliest forms of political caricature were being created to both mock the Catholic Church, and inform more people of the Church’s censorship, political control, and corruption.

In the 1370s, clergy leaders and Pope Gregory XI in England wanted stricter punishments for people who spoke out publicly against the Church. They introduced an Act of Parliament that allowed for the imprisonment of those they considered to be heretics, including people printing negative opinions on the Church. This act became known as De heretico comburendo (regarding the burning of heretics) which was passed by Henry IV in 1401.

Britannica; ACD March 2024

This strict religious censorship had intended to suppress Lollards, who were Proto-Protestants seeking to reform the Catholic Church, by allowing the punishment of burning. Directly below is a wood engraving print depicting the burning of Sir John Cobham, a Lollard, in 1417 in London. Cobham was accused of committing treason in 1413 and due to the passing of the De heretico comburendo act, he was punished by burning. He is shown hanging by chains over a fire with an angry crowd surrounding him holding spears. The print was a part of a book, The Acts and Monuments of John Foxe: A New and Complete Edition, Volume III, edited by Reverend Stephen Reed Cattley in 1837.

Hathitrust; ACD March 2024

Henry IV allowed a range of people to be imprisoned and burned to death if they were considered heretics, including preachers, writers, and teachers. In addition to people being burned, this act also called for any books that contained heretic material to be burned as well. There had not necessarily been as much push for laws against speaking against the government; most of the laws created were intended to protect the Church.

This was still an issue due to the fact that the Church had a great amount of influence and power in England. Church authorities were considered to be more powerful than political leaders, so things they said and did had more of an impact. This meant that speaking out against the Church was essentially speaking out against the government. Other countries in Europe had similar laws in place such as Germany, France, and Spain. These countries enacted censorship on the few things being published by people resisting Church ideals.

However, this began to change in the early 16th century due to the Protestant Reformation and the earlier invention of the printing press in the 15th century. Those in support of Martin Luther’s ideas, known as Lutherans, did not support the Catholic Church and began using visual satire to convey their ideas. This was beneficial to them as it allowed more people to see information about their beliefs and intended reforms, since the literacy rate was still low in many Western European countries, England and the Netherlands reached 53 percent by the early 17th century, but others had yet to even reach half, and images were easier to understand (Eskelson, “States, Institutions, and Literacy Rates in Early-Modern Western Europe”, pg. 112).

Britannica; ACD March 2024

During this period of printing fervor, it was not as easy to censor and ban material because the printing press had allowed publications to be printed more rapidly and in larger quantities. Although the church attempted to burn books and material deemed blasphemous, they were not able to keep up with the rate at which this information was disseminated. Printers who supported the Protestant Reformation published satirical imagery, specifically anti-Papal art like Satire on the Papacy by Melchior Lorck, which depicts the Pope with three heads bribing the military (seen below).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art; ACD March 2024

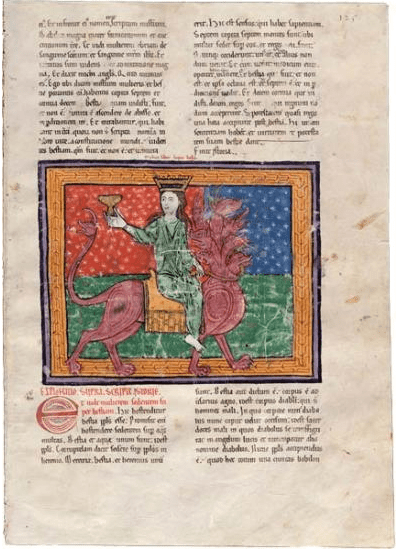

In addition to the creation of anti-papal imagery by those in favor of the reform, Luther and his followers worked to translate the Bible into German, making it more accessible to those who did not read Latin or Greek. This new version of the Bible also contained new imagery that supplemented the passages. The full version of the Bible in his translation was published in 1522, and some of the new images caused controversy like the one alongside the Whore of Babylon from the Book of Revelations.

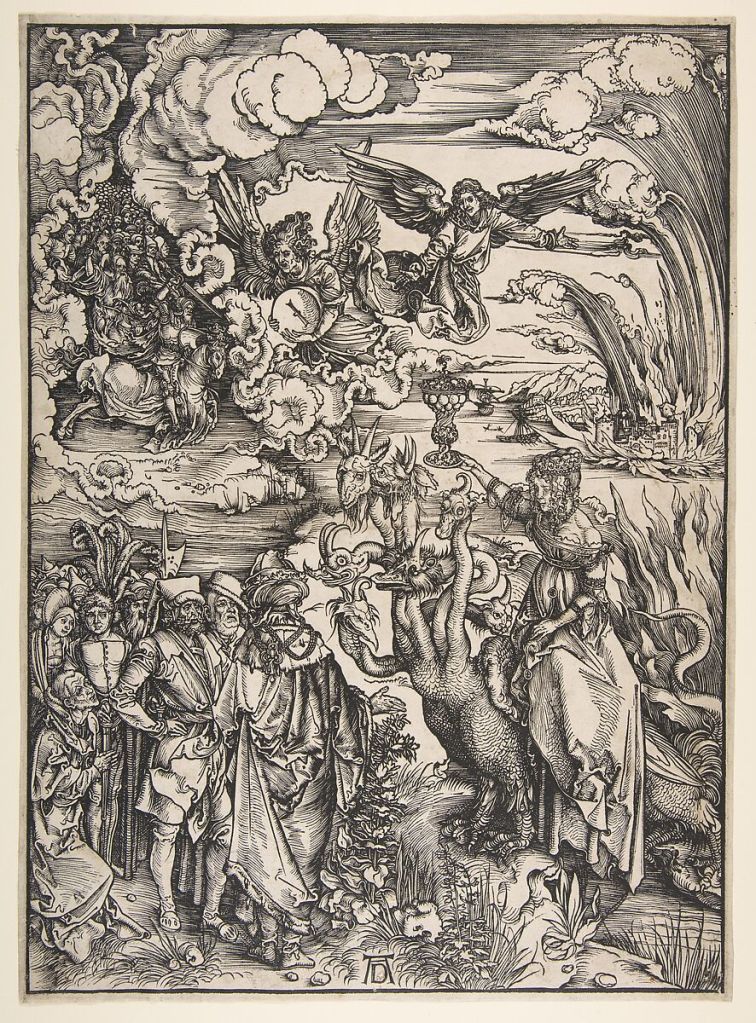

Earlier depictions of this story, like Beatus of Liébana’s illustration, draw the “Whore of Babylon” with a smaller crown, meant to represent one that would be worn by Islamic kings, insinuating that Muslims are the “Whores of Babylon.” This can be seen again during the early fifteenth century with Albrecht Dürer’s 1498 depiction in which the “Whore” is depicted in contemporary Italian clothing, which may be a commentary on the state of Italian citizens.

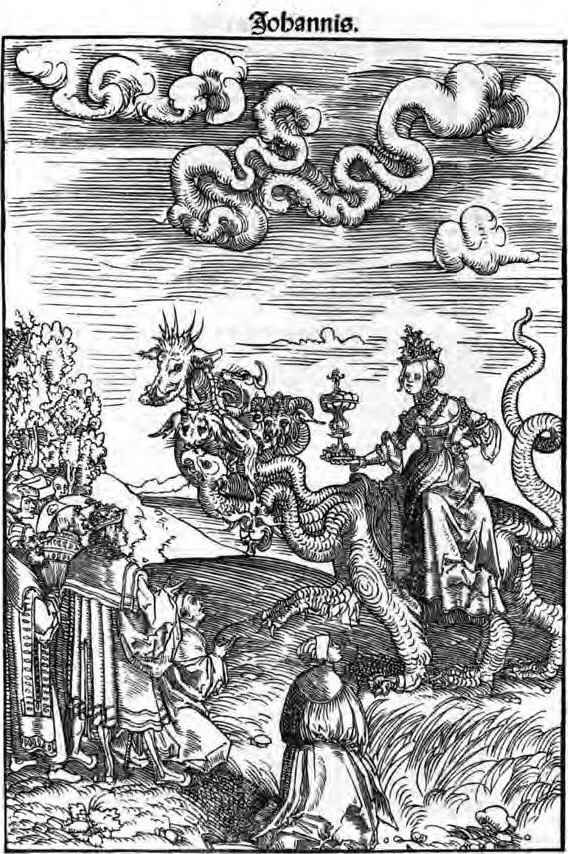

Lucas Cranach was another artist who depicted the “Whore of Babylon,” but he did so for Luther’s new version of the Bible in 1522. Cranach was an artist during the Reformation and a close friend of Luther’s. He produced many religious works of art during the Reformation that aligned more with the Protestant ideals when it came to imagery. However none had been as controversial as his depiction (below on the right) of the “Whore of Babylon.”

The Morgan Library & Museum; ACD March 2024

The Metropolitan Museum of Art; ACD March 2024

Pitts Theology Library; ACD March 2024

The controversial aspect of Cranach’s 1522 rendering of this scene is that the “Whore of Babylon” is drawn wearing the papal tiara, insinuating that the Catholic Church is the personification of evil. This was in fact so controversial that Luther released a second edition of his translation later that year, and Cranach had changed the papal tiara to a single tiered tiara, removing the association with the Church (Pitts Theology Library, Whore of Babylon from the September Testament). However, this was not the last instance of the “Whore of Babylon” representing the Catholic Church and the Pope. In 1545, another edition of the Luther translation of the Bible was published. This edition (below) featured the “Whore” with the papal tiara again. It was based on Cranach’s original illustration and was a woodcut done within Cranach’s workshop. The return to this original depiction could possibly be credited to the overall influence the original had, whether positive or negative.

German History in Documents and Images; ACD March 2024

The work of Luther and other reformers sparked the Counter-Reformation of the Catholic Church in which they made major changes to the way priests were trained for clerical work and emphasized a personal relationship between lay people and God. Much of these changes can be credited to the influential work of both the writings and images of the time. Although these anti-papal images are not considered to be visual satire and caricatures, they hold great similarity to the political cartoons that would develop later on, as they depict figures and symbols that were recognizable to contemporaries and criticized to get a point across regarding their political or religious leadership. For that reason, I would consider them to be the earliest examples of the political cartoon.

Early English Caricature: Depicting Everyday Life

Although Europe saw an increase in the dissemination of books and images after the printing press was invented in 1440, England addressed the issue of censorship with strict regulations through the 17th century. In 1660 Charles II and the Privy Council appointed a Surveyor of the Press to regulate and suppress seditious print or hearsay and utilized a group, known as the Secretaries of State and the Stationer’s Company, to monopolize and regulate the printing industry.

In 1662, Parliament had enacted the Licensing of the Press Act which restricted the content that was printed (Weber, Paper Bullets: Print and Kingship under Charles II). Charles II and Parliament had also been able to control the news through The London Gazette. The Gazette printed news about the government, but its material was highly censored by the king (Tapsell, The Personal Rule of Charles II). With both the Licensing of the Press Act and directly controlling the media, England’s government continued to have strict censorship until around 1680.

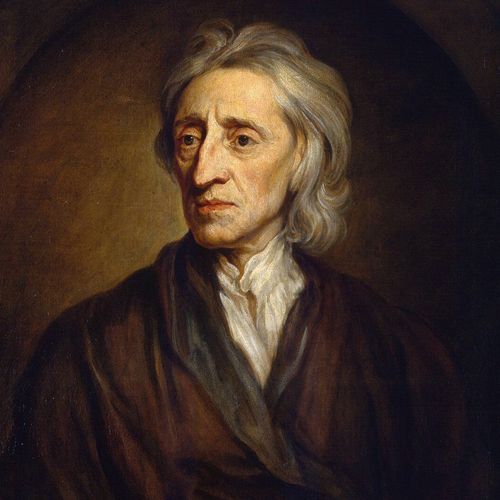

At the end of the seventeenth century and the beginning of the eighteenth century, England and much of Europe was experiencing a period of change called The Enlightenment. The ideas of the Enlightenment surrounded learning and discovery and therefore favored freedom of speech and of the press. One of the most notable Enlightenment thinkers, John Locke, advocated for the expiration of the Licensing of the Press Act and wrote many commentaries on the issue (Locke, Liberty of the Press). Due to advocates like Locke, England let the Licensing Act expire which stimulated the growth of newspapers and other publications.

Biography; ACD March 2024

Within these newfound English newspapers and publications, many artists were inspired to turn to political cartoons and caricatures to share their opinions. Notorious English caricaturists such as James Gillray, Thomas Rowlandson, George Cruikshank, and William Hogarth made a career out of using caricatures and political cartoons to criticize and remark on the state of current affairs and persons of influence.

In Wilkes University Archives’ holdings, specifically the Gilbert Stuart McClintock collection, we have a number of prints by Hogarth of John Wilkes–to read more about Hogarth’s John Wilkes prints, please read our blog post, titled, “Our Namesake: Processing the John Wilkes subseries, 1763-1805, of the Gilbert Stuart McClintock collection, 1549-2015.

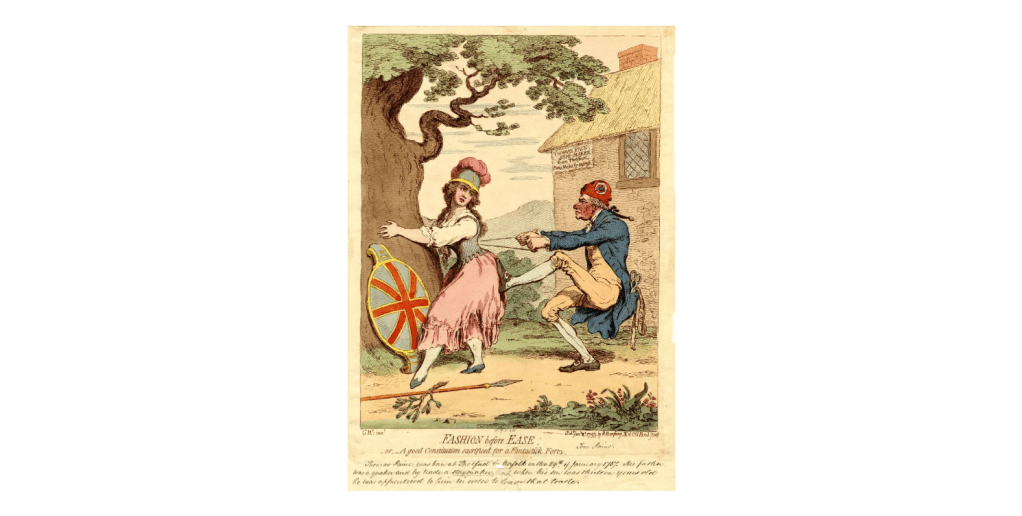

Below are examples of political cartoons published by some of these English artists that depict specific cultural topics that were prevalent for the time period such as dinner parties, high class fashion, industrialization, and political figures like Thomas Paine.

Royal Academy; ACD March 2024

Brooklyn Museum; ACD March 2024

Royal Academy: ACD March 2024

Many of these earlier satirical prints and cartoons published in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in England focused on societal issues that affected the middle class. An example of this from our collection in the archives is a print of an illustration by Thomas Rowlandson, titled, “Miseries of the Table” from 1807, featured below.

Rowlandson commonly drew aspects of 19th century social life in Europe for the upper, middle, and working classes. According to historian Nicholas Robinson, Rowlandson’s “pre-eminence as a caricaturist is based on the brilliance of his line-and-wash rococo drawings depicting humorous social scenes rather than on his political insight” (Caricature and the Regency Crisis: An Irish perspective, p. 175).

This print in particular was for an edition of the 1806 book by James Beresford, titled, The Miseries of Human Life. Beresford wrote the book filled with humorous dialogue between two old men describing the follies and foibles of humankind, which quickly became popular so much so that multiple editions were made by artists who illustrated Beresford’s characters and stories in their own style, like Rowlandson did in the print above. For more information about Beresford’s book and the many illustrations created visit Emmanuel College library’s blog post on artistic editions of The Miseries of Human Life.

This print shows a dinner party scene between a host who served a dish he believed to be perfect and his guests who found it to be an unappetizing and unpleasant smell.

The “fine hare” dish is being carried in with a cloud of steam billowing out towards the table. The guests all try to get away from the plate and block their noses because of the smell.

The caption makes note that the host created this dish specifically for his guests who he knows are fond of it, but they order the plate out of the room. This type of generalized satirical cartoon was common for Rowlandson and while it does not depict a specific figure as those that would appear later on, it is still a humorous caricature detailing the “petty outrages, minor humiliations, and tiny discomforts that make up everyday human existence” (Princeton Art Museum’s collections).

Irish Catholic Emancipation and English Politics Through Caricature

Although in today’s society, most people do not host the kind of lavish dinner parties that were accustomed to those who lived during Rowlandson’s era, this cartoon resonates for anyone who has ever completely botched a recipe or dish that they were planning on serving to friends and family. It’s a testament to the idea that these “miseries of human life” transcend across generations, which makes this cartoon still very humorous today. It is because of this that Rowlandson is considered to be one of the political and social satirists who paved the way for future cartoonists.

While Rowlandson’s Miseries at the Table cartoon is an example of artists who featured broad societal issues that affected the middle class, other artists in nineteenth century England chose to focus their cartoons on specific people, symbols, and topics that were recognizable and relevant in nineteenth century Europe. British artists and printers would intentionally use specific language, colors, and exaggerated imagery as a way to provide their own opinions on national events and significant political issues.

One such political issue that remained prevalent in British cartoons through the late nineteenth century was Irish Catholics and their progression towards emancipation.

Catholics in Ireland were historically oppressed since 1651, when English statesman Oliver Cromwell conquered Ireland following the Eleven Years’ War. England, a predominantly Protestant country, had been in control of Ireland for centuries and implemented anti-Catholic laws in order to suppress the Catholics they had conquered. During the Reformation in England, Henry VII attempted to “reform” Ireland by naming himself the King of Ireland. He also assumed all power the Pope previously had in Ireland, restricting Catholics from practicing freely (Anti-Catholicism in Northern Ireland 1600-1998; p. 16).

The English Crown also established plantations throughout Ireland in the sixteenth century. They forced the Irish-Catholics to work on them as a means of controlling them further, and as a way to profit off their newly conquered territory. However, during the reign of James I, English Protestant settlers moved to Ireland and took over plantations, displacing Catholics.

All Catholics in Ireland who had worked on these plantations and were taken over by the English became “economically dispossessed,” with the end result of the Protestants eventually gaining political and economic privilege entirely by the 1650s (Anti-Catholicism in Northern Ireland 1600-1998; p. 20-27). This economic and political power would continue until the twentieth century, with Catholics in Northern Ireland being oppressed by the Protestants in power.

Throughout the centuries, there had been numerous attempts to ease restrictions placed on Catholics in both England and Northern Ireland with the goal of Catholic emancipation. Restrictions imposed on Irish Catholics under the Irish Parliament’s Penal Laws prohibited Catholics from holding political office, sitting in Parliament, entering the army, navy, legal professions, teaching in schools, sending their children abroad to Catholic schools, as well as restrictions on land ownership (Irish Politics and Social Conflict in the Age of the American Revolution; p. 103).

The first instance of an attempt towards Catholic emancipation was in 1771 with “an act for the reclaiming of unprofitable bogs” that allowed Catholics in Ireland to “take fifty acres of unprofitable bog for sixty-one years” (The History of Catholic Emancipation and the Progress of the Catholic Church in the British Isles; p. 50-51). Despite continual restrictions and rules in place with the Act of 1771, it had been the first time Catholics in Ireland were recognized politically.

In 1760, the Catholic Committee, composed of merchants and landlords, was formed to work towards repealing the Penal Laws. In addition to this committee, the American Revolution inspired many Irish Catholics to take steps towards receiving emancipation. No major discussions occurred towards Catholic emancipation until 1778 within Parliament. In 1778, Parliament finally passed a Catholic Relief Act, which focused on repealing some of the Penal Laws and giving some freedoms to Catholics. This act was a step in the right direction for the emancipation of Irish Catholics, but there were still major struggles with the Penal laws in Ireland.

National Gallery of Ireland, ACD March 2024

Henry Grattan, a member of Irish Parliament, reflected on the Irish Catholic struggle for emancipation in 1782 and said,

In short everyone must admit that England governed Ireland as a tyrant. Perhaps all countries, and all great public bodies, are tyrants. They have no fear of censure, and they do not hear or fear their own disgrace. They have no fear of punishment, and not always a fear of the Deity; so that there is and can be no immediate check over them. No man—at least no Irishman–can read the history of Ireland, or hear the account of England’s treatment of the Irish–without his blood boiling within him.” We cannot wonder that the Irish people, at these various critical periods of their history, did not look up to anyone, for they were cheated almost by every body.

Henry Grattan in 1782, in (Memories of the life and times of Henry Grattan: By his son Henry Grattan,” p. 27-28).

In 1791, another Catholic Relief Act was passed that allowed freedom of worship and removed many other restrictions that had been enacted with the Penal Laws (UK Parliament, Emancipation) such as allowing Catholics to teach in schools, hold public offices, and live within London. This act, however, only granted this relief towards English Catholics.

In 1793 the Irish Parliament passed another Catholic Relief Act that aided Irish Catholics. This Relief Act lifted restrictions on land ownership, voting in certain elections, and holding certain civil offices (The Grail of Catholic Emancipation 1793 to 1829; p. 66-67). While this act removed almost all of the Penal Laws that had still been in effect, it did not grant Catholics total emancipation.

After this act, there was not much progress made towards total Irish Catholic emancipation, however there were many still involved in the cause like Henry Grattan and Daniel O’Connell. Grattan had attempted to propose a bill in 1795 for Catholic emancipation alongside Lord Fitzwilliam to Parliament. He had also presented a petition from Irish Catholics in Dublin to advocate for Catholic emancipation, but Fitzwilliam had been recalled to Ireland by the Duke of Portland, because the Duke and others were unhappy with Fitzwilliam’s work on the bill (Whig Principles and Party Politics. Earl Fitzwilliam and the Whig Party; p.199). Without the support of an official with Fitzwilliam’s title, Grattan’s proposed bill was rejected by Parliament (The Grail of Catholic Emancipation 1793 to 1829; p. 84-90).

From 1807 through 1810, Catholics in Dublin and Grattan would meet and debate whether they should petition again to Parliament and whether to introduce another bill to Parliament (The Grail of Catholic Emancipation 1793 to 1829; p. 144-170). Grattan’s next bill had included clauses from George Canning, who had served in numerous cabinet positions under prime ministers. This bill was proposed and went through numerous changes before finally being accepted in 1813.

In 1813 the bill was passed in Parliament that allowed Irish Catholics in England to hold civil and military positions, keep arms, and vote, known as “the Bill of 1813” (The Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland; p. 566 ). The passing of this bill had been a substantial step forward for Catholic emancipation in Ireland, but there was still opposition from Protestant groups against permitting Irish Catholics to possess these civil liberties.

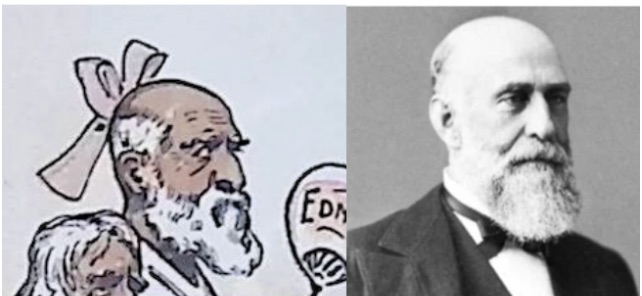

Following the passing of this bill, there had also been another bill brought to Parliament, introduced by Henry Grattan again, in 1813 called the Catholic Bill, that specifically addressed Catholic emancipation in Ireland (Memoirs of the life and times of Henry Grattan; p. 558). However, this bill was met with much opposition from the Orange Order and Protestants like Lord Mayor Abraham Bradley King (Brabazon, Outlines of the History of Ireland). It was also strongly opposed by Irish Catholics like Daniel O’Connell because the bill would have given Parliament the right to veto papal appointments of bishops in the UK, which would have led to Protestant intervention in Catholic Church affairs as well as deterred his primary cause of eventual Irish national independence (The Irish Experience in 1800: A Concise History).

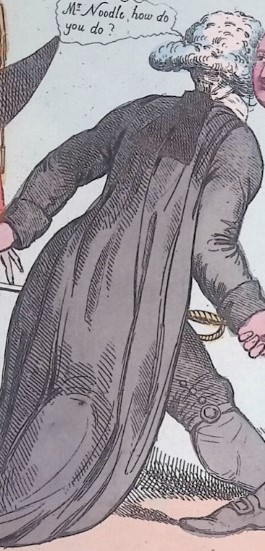

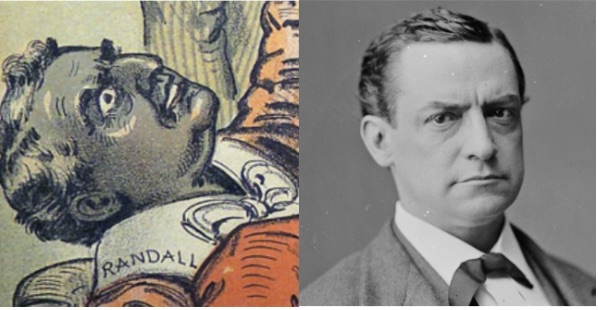

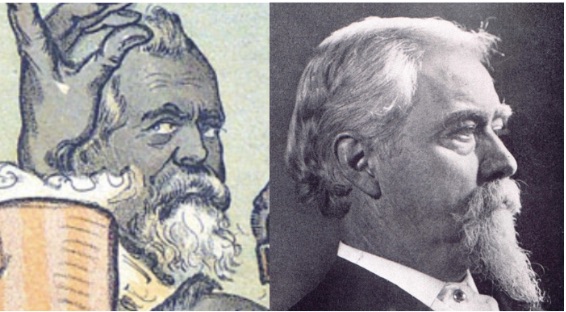

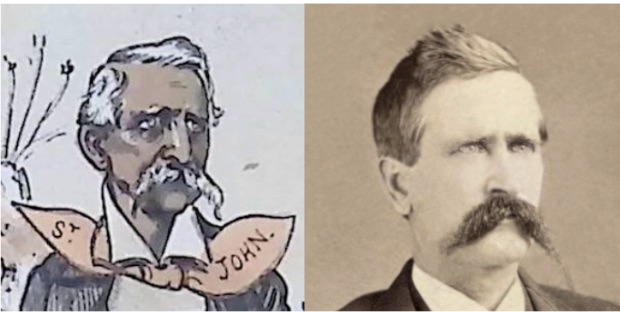

During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century many cartoonists and printers in England and Ireland were creating cartoons on the issue of Catholic emancipation, presenting various aspects of the conflict. One of these cartoons that depict the success of King’s petition against Catholic emancipation is “The Meeting of Doodle and Noodle” from 1813 that was created and published by J. Sidebotham, featured below.

Sidebotham created this cartoon, and a series of others, depicting Abraham Bradley King during his time as Lord Mayor of Dublin.

Abraham Bradley King was the son of an army officer and held many prominent positions in nineteenth century Dublin. He was elected as sheriff of Dublin in 1801, a captain in the Dublin yeomanry in 1803, and in 1812 he served his first term as Lord Mayor of Dublin. In this position he was chairman of the Dublin City Council and gained the right to present petitions directly to the House of Commons in Westminster. He was also a member and eventually became the grand deputy master of the Orange Order, a political society named after William of Orange, or King William III, that was created to maintain Protestant authority in Ireland. The Orange Order and King in his role as Lord Mayor were active in suppressing Catholic emancipation.

In the cartoon, King, shown as “Mr. Noodle” (facing us) is pictured shaking hands with “Mr. Doodle,” (his back to us) known as George Scholey, Lord Mayor of London, who was in support of his petition to stop Catholic emancipation. Sidebotham’s use of portraying King and Scholey as “Mr. Noodle” and “Mr. Doodle” is meant to imply that both political figures come across as the same foolish persona. The term, “doodle” has origins from German, or Dödel, meaning “simpleton” or “fool.” According to the Oxford English Dictionary, “doodle” and “noodle” had the same connotation by 1764 of meaning “silly or foolish fellow” (Oxford English Dictionary), and many literary references during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries “put doodle in close contact with comical and underachieving men” (Yankees, Doodles, Fops, and Cuckolds: Compromised Manhood and Provincialism in the Revolutionary Period; p. 528-529). Sidebotham’s use of these colloquial terms to imply that King and Scholey were imprudent civil servants possibly reveals a common public perception of both figures.

New York Public Library; ACD December 2023

Given that Sidebotham included sarcastic dialogue on the petition, and due to the way he depicts King by calling him “noodle,” it seems that he disagreed with King and his time as Lord Mayor. What’s interesting to analyze about the cartoon is the sarcastically excited dialogue being presented alongside the art:

The dialogue blurb between the footmen in the background states, “Oh! This is a day of Jubilee. Cajollery A day we never saw before, a Day of Fun & Drollery!” and the other footman states, “That you may say, the Orangemen may boast of it And since it never can come more ‘Tis fit they make the most of it!” However when you look at the faces of the footmen, they appear to be very serious and concerned. The artist has drawn frowns on each of their faces instead of smiles. This suggests that the dialogue presented is actually meant to be sarcastic suggesting Sidebotham is mocking the petition and the event as a whole.

While this specific bill from 1813 may not be very well known now, the fact that so many different cartoons in 1813 commented on King’s visit to the House of Commons demonstrates how monumental emancipation was for Irish Catholics. In addition to this cartoon, Sidebotham published other cartoons in 1813, likely by the same artists, covering the same topic of King’s petition. The one by Sidebotham featured below was titled, “A Race to the Regent or the Stationary Mayor of Dublin going to London with a Petition against Catholic Emancipation!”

In this cartoon, Lord Mayor Abraham King is traveling to London with a group of other Protestants to deliver their petition against Catholic emancipation. The carriage is carrying scrolls saying things like “Abraham’s Faith, the way to get appointed to supply the public Offices in Dublin with Stationary,” “Statement of Penal laws,” and “Protestant petition.” The Protestants are going to present the petition to George IV, Prince regent, during his levee, in the hopes he would reject the Catholic emancipation bill.

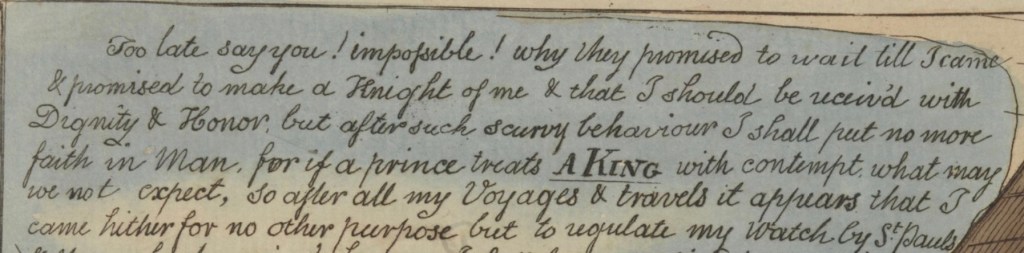

William McClearly’s “The Late Lord Mayor! Or Abraham in the Land of Promise!” featured below was also published in 1813 and depicts Abraham Bradley King, with a scroll titled, “Protestant petition against Catholic Emancipation,” entering Carlton House, the residence of George IV. He was likely trying to show George IV his petition, but is being told he was too late to the levee. Below is the cartoon.

Trinity College Dublin; ACD January 2024

McCleary is mocking King through his dialogue. King’s dialogue blurb quotes him saying the following :

McCleary’s inclusion of King’s self-important dialogue conveys King as extremely conceited: his dialogue shows his shock in not being considered important enough to meet with George IV during his levee. It’s possible that McClearly is attempting to depict Abraham Bradley King’s lack of influence over King George IV within the cartoon.

Although King George III had opposed Catholic emancipation during his reign, his son, Prince regent George IV, in opposition of his father, was thought to initially support emancipation as he was friends with Whig politician and Catholic supporter Charles James Fox and had numerous Catholic mistresses (Abject Loyalty: Nationalism and Monarchy in Ireland During the Reign of Queen Victoria, p. 4-5). However, the Duke of Cumberland believed granting rights to Catholics would be in violation of the King’s coronation oath to uphold Anglicism and convinced George IV to reject Grattan’s Catholic Emancipation bill in 1813 (Abject Loyalty: Nationalism and Monarchy in Ireland During the Reign of Queen Victoria, p. 4-5).

So it was Cumberland’s influence, not King’s, which ultimately drove King George into obstructing the passing of the 1813 emancipation bill. While there are no current sources to confirm McCleary’s personal beliefs about Catholic emancipation, it is clear that within his cartoon above, he is personally making fun of Abraham King.

After the 1813 Catholic bill was rejected by Parliament, little progress was made for another Catholic emancipation bill until the 1820s. Tensions in Ireland had been high between Irish Protestants and Catholics in the early 19th century as many Catholics were continually met with violence. There were instances of families being burned, Catholics being murdered and their corpses being hung, and farmers being attacked in the 1810s (Ireland: The Politics of Enmity; p. 95-99).

Violence continued to rampage Ireland as both Protestants and Catholics were dissatisfied with the King and Parliament. Catholic agrarian associations were formed to rebel against the political and economic disparities. When they were founded in the late eighteenth century, many destroyed properties of Protestant landlords, but they soon moved on to more extreme violent acts to get their message across. By 1800, Protestant clergy members started to become victims of these attacks (Secret Societies and Agrarian Violence in Ireland; p. 370-374).

Renewed efforts to pass an emancipation bill occurred in March 1821 within the House of Commons, however it was defeated by the House of Lords, due to Cumberland and York’s influence over the King. There was continued outrage from both Protestants and Catholics over the way Parliament was handling the topic of emancipation. Having just lost a war with the American colonies that originated from a revolution, Parliament wanted to do what they could to alleviate these tensions. Since the topic of Catholic emancipation was so intense and was not yielding immediate results, other methods were used to keep any rebellion or civil war from ensuing.

In I821, King George IV’s visit to Ireland was seen as a renewed attempt to bring promise of change between Ireland and the British Crown. While publicly the visit had been viewed as a sign that England had wanted to work with Ireland, and many felt this meant a major step towards emancipation, it was in fact a motivated effort to increase George IV’s popularity. People had shown strong dislike towards the newly crowned King, likely due to high taxes from the Napoleonic Wars, and the King’s conflict with his wife that had been fairly public. George IV’s private secretary had arranged the visit to Ireland in hopes of increasing the King’s popularity by having the visit appear to be him looking into the ‘unnatural poverty … amidst a superabundance of wealth” (Holton, All our joys will be complated: the visit of George IV to Ireland, 1821; p. 249-250).

The King’s administration had feared violence and riots during the King’s visit in Ireland, so as a preemptive measure, Dublin Castle issued a “public letter” to the people of Ireland to assure them that the King was coming to offer peace and they should try to gain his support as it would be beneficial to their interests. Daniel O’Connell, a frontman of the emancipation movement, saw his visit as an opportunity to gain the support of the King in hopes of reaching his goal of emancipation (Holton, All our joys will be complated: the visit of George IV to Ireland, 1821; p. 252). In addition to Daniel O’Connell meeting with the King, Abraham Bradley King, Lord Mayor of Dublin, had been sent to meet the King as well.

On the eve before the king’s arrival to Ireland, Abraham Bradley King held a meeting among Dublin citizens and a motion was decided to put aside the wearing of Protestant (yellow) and Catholic (green) colors in exchange for a universal Irish blue. O’Connell supported this idea and during the visit presented an address to the king announcing his loyalty to the crown (The life of Daniel O’Connell; p.109-111). Many were disturbed and confused by O’Connell’s flattering displays, such as the former anti-Catholic Lord Chancellor of Ireland Lord Redesdale, who wrote in a letter that it was “ridiculous to find O’Connell a flaming courtier” (The life of Daniel O’Connell; p.109-111).

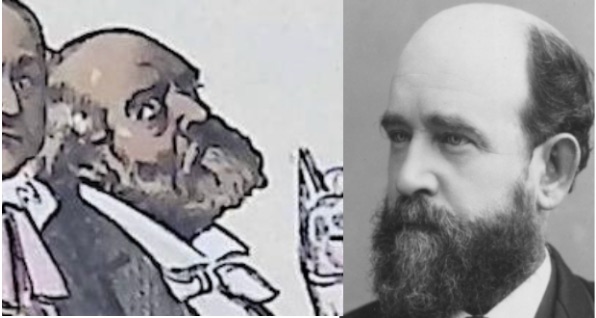

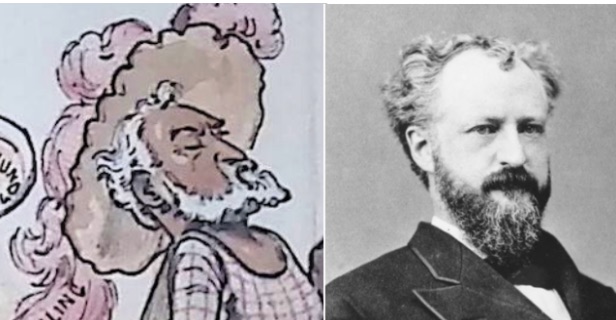

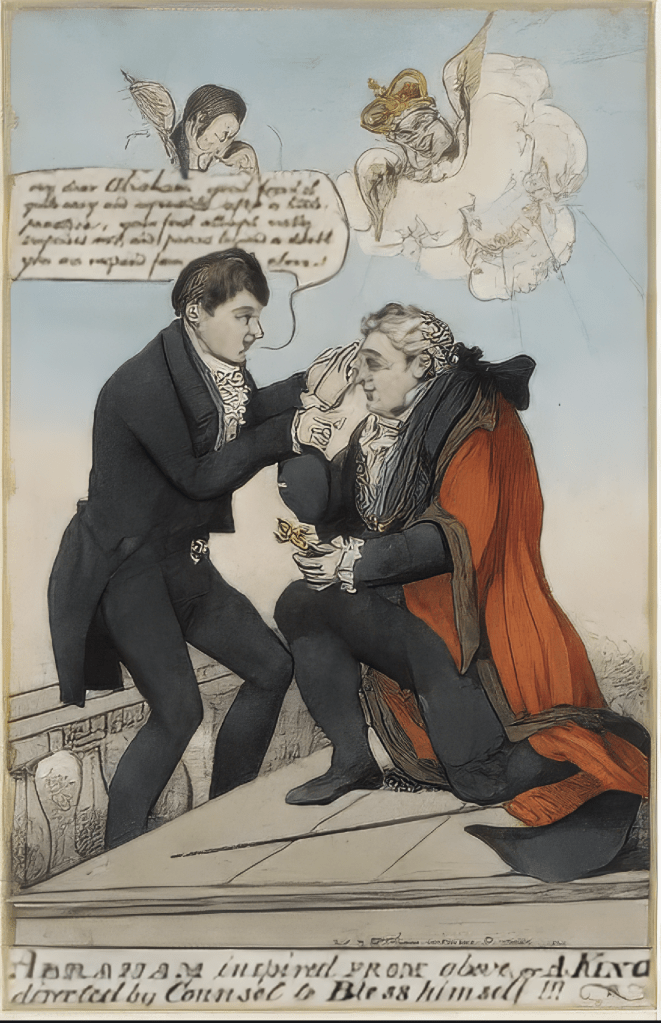

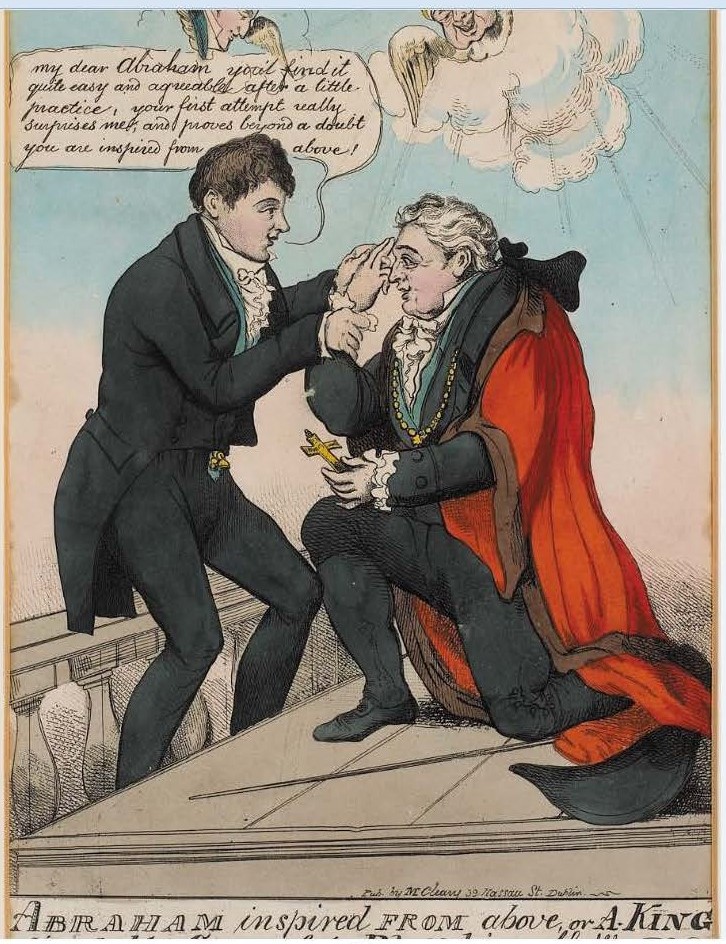

Below is a cartoon published in 1821 by William McClearly of an imaginary conversion to Catholicism of Abraham Bradley King. On the left is Daniel O’Connell counseling a kneeling King on the right, and says, “my dear Abraham, you’ll find it quite easy and agreeable after a little practice, your first attempt really surprises me, and proves beyond a doubt that you are inspired from above!” Depicted flying above them are seagulls with the heads of Arthur Wellesley, the 1st Duke of Wellington, (left) and King George IV (right). The Duke of Wellington is likely situated flying next to King George IV because like the King, he was strongly opposed to the idea of Catholic emancipation and expressed his dislike of O’Connell and his ideas (The Eve of Catholic Emancipation; p. 213). He was also frequently involved in voting against bills that were introduced to Parliament that supported Catholic emancipation.

This cartoon was likely created after the King’s visit to Ireland, because in addition to King’s motion of wearing blue during George IV’s visit, he had also banned the decorating of William of Orange’s statue that had been a tradition, in hopes of keeping tensions between Protestants and Catholics to a minimum. Many of King’s supporters who were members of the Orange Order were infuriated by King’s action of banning their tradition of decorating the statue, and many of them decorated it in defiance. In response, King withdrew from the Orange Order and his position within the order as deputy grand master (The Life and Speeches of Daniel O’Connell, M.P.; p. 328). He had most likely banned the decorating of the statue in order to appease Catholics and ensure there would be no fighting between Protestants and Catholics during the King’s visit. He also likely stepped down from the Order so he would be able to keep his position as Lord Mayor.

These Williamite festival bans were not only enforced during King George IV’s visit but after as well. He permanently banned the William of Orange ceremonies for Orangemen who desired to use these celebrations as a means to resist concessions to the Catholic population (The Theatre Royal bottle riot of 1822 and the Orange Order in Dublin, p.176). This also influenced Abraham King to step down as the Deputy Grand Master of the Orange Order. McCleary is most likely commenting on Abraham kowtowing to Catholic concessions from O’Connell and above from the king and the Duke of Wellington. It is likely that McCleary is mocking both O’Connell’s and Abraham King’s recent behaviors of working together during the King’s visit to Ireland, and that they both had their own specific intentions in doing so.

Abraham King’s banning of Orange Order activities and their retaliation would not be the last time there were conflicts between members of the order and officials in Ireland. The King appointed Richard, Lord Wellesley, former Governor-General of India and a Catholic emancipation supporter, as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in December 1821. He attempted to propitiate the Catholic population with the decision to dismiss the Attorney General of Ireland, Wiliam Saurin, whose fifteen year anti-Catholic dominion in Ireland finally came to an end with the discovery of a letter he wrote to Lord Norbury in 1822 in which he urged him to “judiciously administer” his influence over Protestant local juries to vote against Catholics (Sheil’s Sketches of the Irish Bar, Volumes 1-2,p.34). Wellesley enforced the king’s decision to restrict Williamite celebrations.

A mob of Orangemen rioted at a theater performance that Wellesley attended, which became known as the Bottle riot, in an attempt to forcibly remove Wellesley from his position. This attempt failed and news of this riot reached Parliament. Parliament spent days investigating and interrogating rioters but their protection of each other with support from Protestant Parliament members resulted in the case being dismissed. Although their governmental inquiry resulted in no prosecution of bottle rioters, the Orange Order’s influence in Ireland had greatly diminished after these series of events.

These supportive measures towards the Catholic population resulted in the creation of the Catholic Association, an organization spearheaded by Daniel O’Connell in 1823. O’Connell was an Irish lawyer who was persistently involved in the fight for Catholic emancipation, and the association grew exponentially under his influence and leadership; O’Connell successfully raised financial support among wealthy Catholic landlords and peasants alike, unifying them to join, especially with the cost of membership being a pound each (The Life and Times of Daniel O’Connell; p. 295). By late 1820s, the emancipation cause became the focal political issue in Ireland.

O’Connell and the Catholic Association’s campaigns were not well received in England or in Ireland among the Protestant population; those in power in England were becoming wary of the large public protests organized by the Catholic Association. Seeing the larger scale gatherings of angry Catholics, Parliament feared riots or even more violence.The Duke of Wellington, who was a staunch opponent of O’Connell, was noted for saying “If we cannot get rid of the Catholic Association, we must look to civil war in Ireland sooner or later” (Sir Robert Peel: from his private papers; p. 348). Parliament began fearing a rebellion or civil war would ensue in Ireland, so once again they began discussing a new bill for Catholic emancipation.

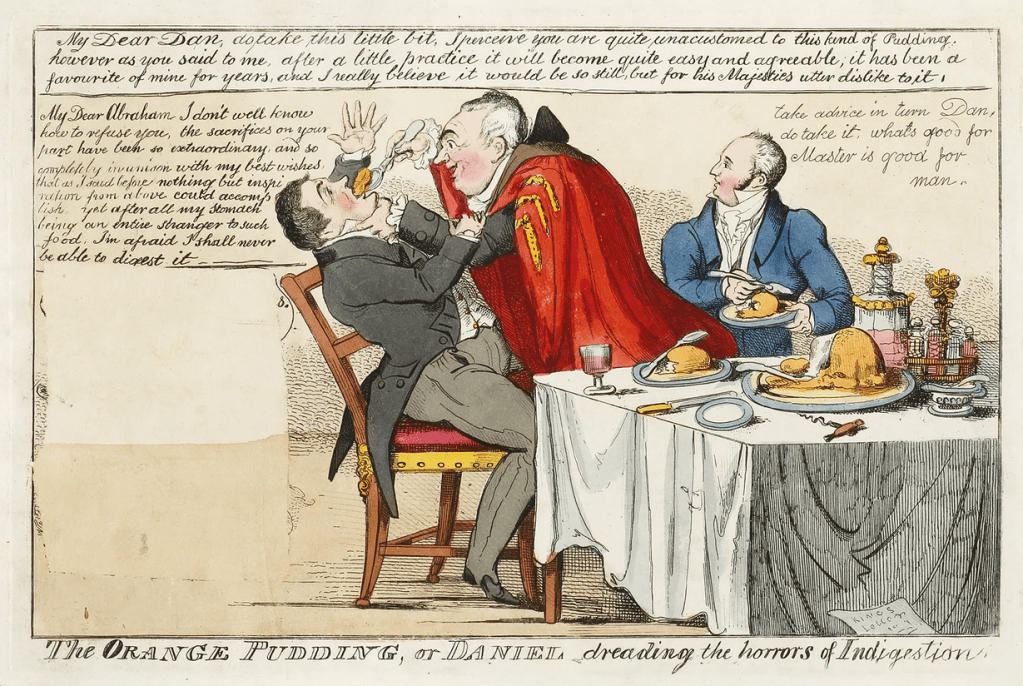

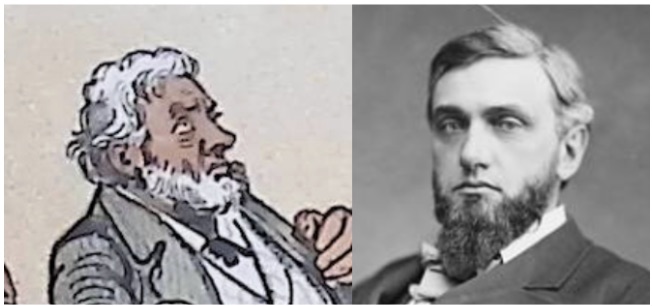

This 1823 cartoon featured below by William McCleary, titled, “The Orange Pudding, or Daniel dreading the horrors of indigestion” is a political commentary on the nature of Daniel O’Connell’s influence on the Catholic emancipation cause. In the cartoon, King is shoving orange pudding into Daniel O’Connell’s mouth.

Antique Print & Map Room; ACD January 2024

King says,

“My dear Dan, do take this little bit, I perceive you are quite unaccustomed to this kind of Pudding however as you said to me, after a little practice, it will become quiet easy and agreeable, it has been a favourite of mine for years, and I really believe it would be so still, but for his Majesties utter dislike to it.”

O’Connell’s reply is

“My Dear Abraham I don’t well know how to refuse you, the sacrifices on your part have been so extraordinary, and so completely in unison with my best wishes that as I said before nothing but inspiration from above could accomplish, yet afterall my stomach being an entire stranger to such food, I’m afraid I shall never be able to digest it.”

This cartoon comes across as more violent than others we’ve seen of McCleary’s perspective on the Catholic emancipation issue. By 1823, King was no longer Lord Mayor of Dublin, in fact, after the bottle riots, he resigned from his post, as the riots occurred under his watch and he was implicated as being complicit with their actions due to being a previous member and leader of the Orange Order. The imagery of King with his hand around O’Connell’s throat while shoving orange pudding down is likely meant to represent the act of King forcing O’Connell to accept the Orange Order and persuade him to stop supporting Catholic emancipation. Both O’Connell and King were strongly opposed to the bill presented in 1813 for Catholic emancipation, but for different reasons. King was a Protestant and member of the Orange Order, and had made it clear he did not support the idea of Catholic emancipation. O’Connell did support Catholic emancipation wholeheartedly, but as mentioned previously, he did not agree with the terms presented alongside the bill. It is possible that because of this, O’Connell and King worked together to prevent the bill from being passed (Historical Sketches of O’Connell and His Friends; p. 187-188).

The response from O’Connell in this cartoon is fascinating from McCleary’s perspective because to me, it shows O’Connell in a very compromising manner. McClearly’s take on O’Connell’s response is most likely meant to be interpreted sarcastically, with obvious slights in certain lines (King’s “sacrifices…have been so extraordinary and so in unison on my part”), which is likely a reference to their heavy handed legal relationship, but his response could also be viewed as weak and submissive.

O’Connell was a significant political voice in Ireland and although he held strong personal beliefs of Catholic emancipation and a desire for eventual Irish independence, his prominent connections with Protestants in power and in effectuating Catholic reforms required an ability to tow the line between Catholics and Protestants demands during this time. Through the early 1800s, he often had to acquiesce to those in power in order to maintain a seat at the political table for the long term goals he had for his country and his people. His political balancing act and double sided nature reveals why he is a figure that continuously shows up in cartoons on this political issue.

Both the Catholic Association’s protests and O’Connell running for office in 1828 instigated shifts in discussions within Parliament. However, another major contributor to reform was likely shifting public opinions among the Whigs in the House of Lords and the followers of Lord Grenville who supported Catholic emancipation in Ireland. Eventually due to the persistence of O’Connell, the Catholic Association, and Parliament’s fear of civil unrest, another relief act was passed in 1829 called the Roman Catholic Relief Act, which allowed Roman Catholics to run for Parliament and other offices. Most importantly, the act removed Parliament from having power over the Catholic Church in Ireland (University of Nottingham Manuscripts and Special Collections, “Daniel O’Connell”).

Sidebotham and McCleary’s continual publishing of material on the topic of Catholic emancipation and figures like King, Scholey, and O’Connell show that there was a demand and audience for this political issue. The rise in publishing political cartoons and newspaper articles that publicly supported Catholic emancipation and criticized British and Irish politicians who opposed it kept this issue in the public consciousness. This may have led to the eventual support for Catholic emancipation among the House of Commons by the late 1810s, and by the House of Lords by the late 1820s. This may have been due to fear of sparking a religious civil war in Ireland. This act removed the most important restrictions of the Penal Laws, and is considered to be so important to emancipation because it gave Catholics a voice in Parliament and the decisions that would impact them.

The Rising Popularity of Caricature and Rivalries in Irish Print-Making

The burgeoning market for political cartoons and caricatures in England and Ireland in the early nineteenth century allowed printers like Sidebotham and McCleary to publish cartoons on topics like Catholic emancipation because of the popular demand for these kinds of prints. Initially, many artists in Europe, specifically in London and Dublin, printed their work through smaller publishing houses. Either artists would approach printers with cartoon ideas, or more commonly, printers would hire artists to create their specific ideas for cartoons.

By 1780, printers had access to William Reeves’ invention of “hard cakes of soluble watercolour” which streamlined the process of color printing, compared to the previous arduous task of artists having to mix their own pigments (English Heritage, Satire and Scandal: Media in 18th-Century England). Additionally they had resources needed to create prints and employees to aid in the printing process. This created a more efficient method for getting cartoons reprinted and circulated than if an artist was printing by himself. Individual prints were often advertised in newspapers or circulated through coffee houses or displayed in shop windows to attract customers. Satirical cartoons were also included in pamphlets to spread relevant ideas and humorous prints to audiences that grew increasingly interested in them (English Heritage, Satire and Scandal: Media in 18th-Century England).

In addition to publishers putting out singular prints, smaller magazines that would feature a collection of English prints also became popular and would be sold across Europe. One of these was The Hibernian Journal run out of Dublin by Thomas Walker. Walker operated at 79 Dame Street in London from 1771 to 1812 would regularly produce popular plates of English caricatures. There was high demand in Dublin for English prints specifically and printers, like Walker, profited greatly off reproducing prints from London (The Printshop Window: Caricature & Graphic Satire in the Long Eighteenth Century).

Aside from magazines like Walker’s, there were many notable printers capitalizing on the demand for satirical prints like William Allen, J. Sidebotham, William McCleary, and S.W. Fores. Each of these men became well known within the Irish printing industry, either from producing original prints or pirated copies.

William Allen was a popular “map and print seller” working out of 32 Dame Street in Dublin, who specialized in caricatures on social issues and events (Robinson, “Caricature and the Regency Crisis: An Irish Perspective,” p. 173). He, like many other Dublin printers during this time, printed copies of London prints, but also the work of Henry Bunbury.

J. Sidebotham worked out of London and Dublin from 1802 to the 1820s. For most of his career he held a print shop at 24 Lower Sackville Street in Dublin from 1802 to 1813. Earlier in his career, many of Sidebotham’s early prints were copies of other English satire artists like Charles Williams, but he later desired to establish original caricature designs.

William McCleary, another printer working out of Dublin, had also been reproducing English prints copied from London, however he had also reproduced prints identical to some of those created by Sidebotham.

S.W. Fores published prints out of London from 1783 to 1838. He would print illustrations by James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson, as well as his own work. Below is an example of one of his cartoons, titled, “Love’s Last Shift” which depicts a scene related to the seventeenth century English play, Love’s Last Shift by Colley Cibber. It depicts George IV with his wife and child as characters in Love’s Last Shift.

British Museum; ACD January 2023

Since there had been such high demand for English prints, some printers would copy one another in order to maximize the amount of prints they were producing. This was a fairly common practice during this political cartoon printing surge and it’s the reason why it can be difficult to figure out who created the original caricature or cartoon.

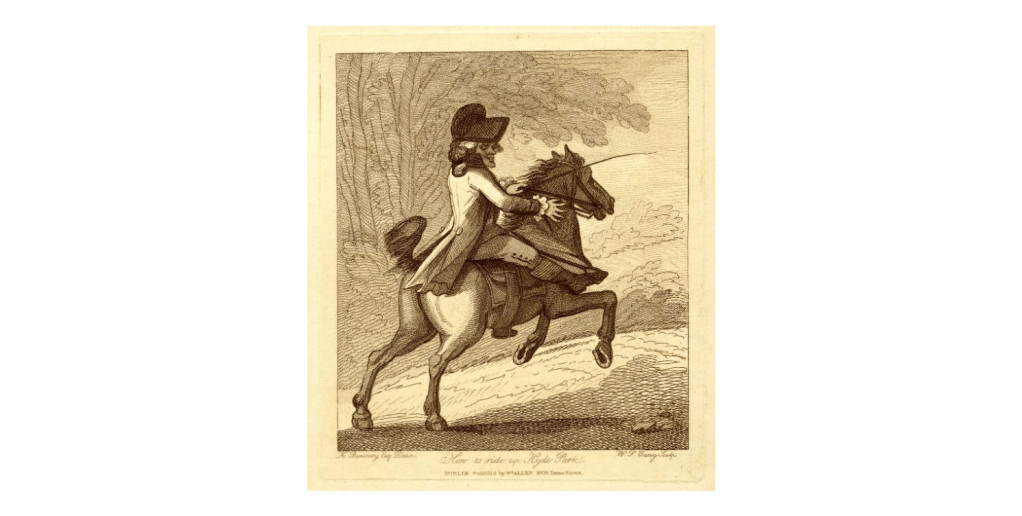

One cartoon published by William Allen, titled, “How to ride up Hyde Park,” which caricatures a man riding a horse. This is likely not the original edition of “How to ride up Hyde Park,” as the original is likely the image on the left created by Henry Bunbury from 1786. William Allen then created another rendition of the image around 1787 to 1790. Bunbury then included another rendition of the image in a book titled An Academy for grown horsemen in 1796 by Geoffrey Gambado, a pseudonym for Henry Bunbury. This book contained different humorous caricatures of men riding horses. The image was also recreated once again in 1808 by Thomas Rowlandson depicting a similar character on a horse, but added a scene.

Yale University Library; ACD March 2024

British Museum; ACD March 2024

The Metropolitan Museum of Art; ACD March 2024

These prints complicate the topic of piracy and copying in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. While they are all recreations of Henry Bunbury’s original idea, they each add to it with their own style. In this case, it can be argued either way, that Allen and Rowlandson were copying Bunbury, or that they added enough to them to make it “original.” However, many other printers were more blatant and less creative with their copying, like J. Sidebotham.

One of Sidebotham’s prints titled, “The Ghost of a Guinea or the Country Banker’s Surprise” (left below) from 1810, which comments on how bankers reacted to guinea coins with George III’s face on them, appears to have been a copy of another cartoon by George Woodward from 1804 (below on the right), just inverted. We can tell Woodward’s is the original, because it was published six years before Sidebotham’s print, and because it overall appears to be a cleaner print.

British Museum; ACD March 2024

Library of Congress; ACD March 2024

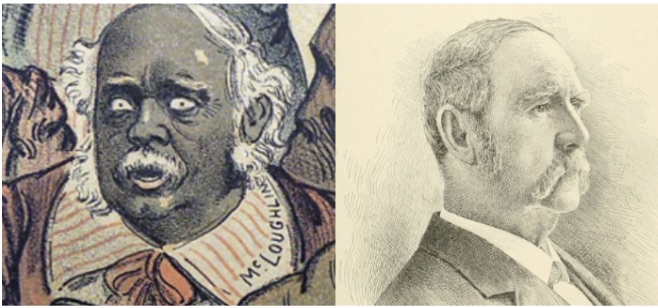

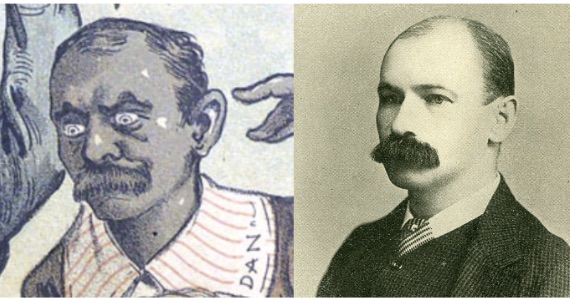

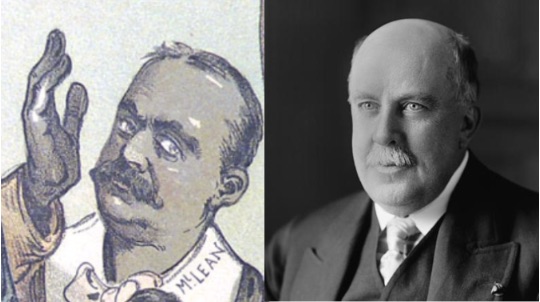

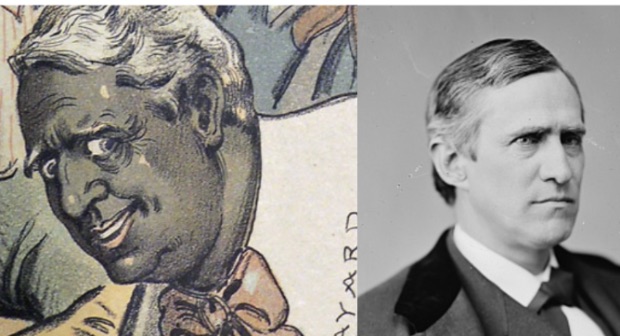

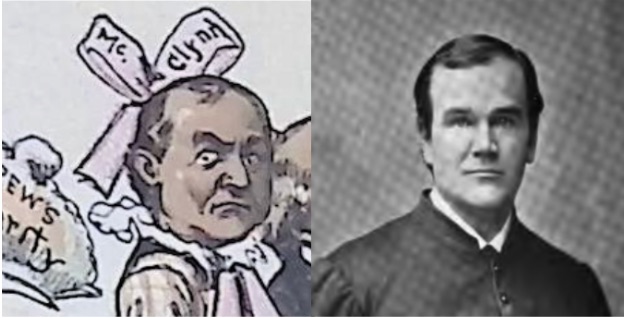

Reproductions of British political cartoons spurred intense rivalries between individual printers, like J. Sidebotham and William McCleary, who were trying to make profits off of their cartoons. The feud between McCleary and Sidebotham became very public as McCleary was known by 1809 to have copied at least 10 of Sidebotham’s original caricatures and sold the copied versions at reduced price (The Printshop Window: Caricature & Graphic Satire in the Long Eighteenth Century). This spawned a new level of resentment from Sidebotham so much so that he began to caricature McCleary within his prints as well as include a message surrounding his prints, like in “The Meeting of Doodle and Noodle,” in which he “cautions the public against McCleary of N° 32 Nassau St & his spurious copies of all S’s Original Caricatures. A zoomed in screenshot is featured below.

Although neither printer’s editions for each print contain a specific date, so it can not be proven exactly which printer created the image first, from the outset, Sidebotham had invested more in the publication of original caricature designs, so it is more likely that the original print is from him. He made a point to publish these accusations of McClearly, though did not mention him specifically by name, on May 10, 1881 in an announcement in the Freeman’s Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser:

In this newspaper announcement, Sidebotham publicly criticizes McCleary for getting copies of his new caricatures by “tampering with some of the people employed” in order to print his own recreations. Sidebotham offers a reward to anyone who is able to prove what McCleary did.

However, it is interesting to note that after being pirated from other printers like McClearly in Dublin, when Sidebotham eventually moved to London to break into the publishing industry there, he did the exact same thing to other cartoonists and printers from London. One instance of this was when he had written to another printer, William Hone, to ask for impressions of one of his caricatures for “less than cost price.” If Hone chose not to sell it, Sidebotham threatened to pirate Hone’s caricature and sell it anyway. He had an artist recreate the prints upon Hone’s refusal, and had the copies sent to Hone asking him to exchange them for originals, which Hone did not. This is a perfect example of the printing industry for caricatures during the nineteenth century (William Hone: His Life and Times; p. 106-107). Demands for prints were high, and printers were able to make quick money by reproducing copies of others prints. There had to be extreme measures taken to ensure other printers did not replicate their prints. It was also common for printers, like Sidebotham, to attempt to convince artists to create the replications for them.

Sidebotham’s attempts to create a thriving printing business in London included soliciting artist George Cruikshank to allow him to make copies of his cartoons. He had also wanted Cruikshank to create copies of prints from other artists, like William Hone, and when he did not, Sidebotham created a copy of a print by Cruikshank that had been published by Hone. Despite this, in the same month Cruikshank still created an etching designed by Sidebotham for him to print. Cruikshank continued working with Sidebotham on different prints, creating both originals, and aiding him in creating slightly altered piracies (George Cruikshank’s Life, Times, and Art; p. 126, 189).

The Drama of King George IV’s Court

It’s no surprise that printers like Sidebotham sought after the talented works of George Cruikshank as he was one of the most well known English caricature artists of the nineteenth century. His father, Isaac Cruikshank, was a cartoonist as well and had a studio where George apprenticed. He began his career working with printer William Hone on political satires. He had begun to create his own caricatures and was featured in a monthly magazine, The Scourge from 1811 to 1814, where he commonly caricatured King George IV and English politicians. While working with William Hone, Cruikshank published even more caricatures criticizing the Crown. As a result, King George IV attempted to bribe him to keep Cruikshank from publishing his caricature. Later in his career he focused on book illustrations, but his political caricature was very influential during its time (Illustration History, George Cruikshank).

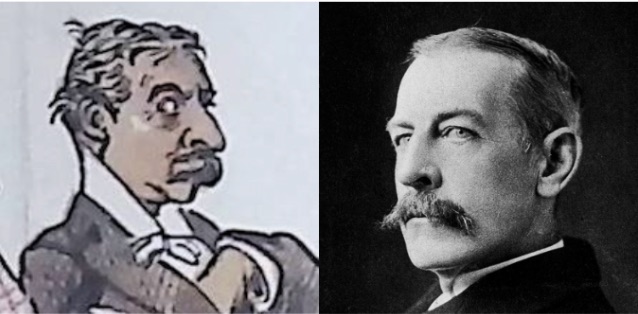

Below is a cartoon Cruikshank created in 1822, titled, “Rumping–Kicking and Kissing–or cutting off the privy purse” in which he uses his notoriety to comment on rumors involved with the royal family.

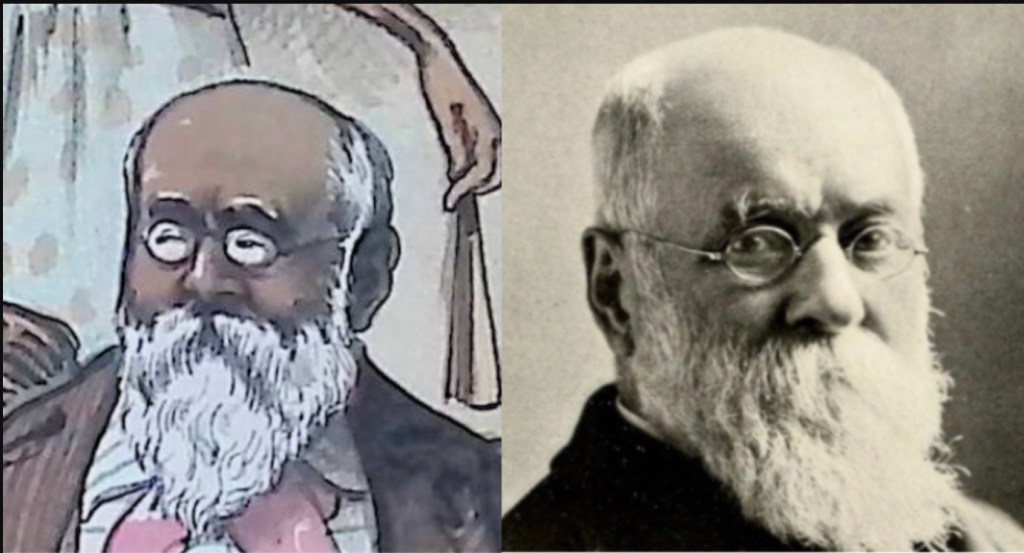

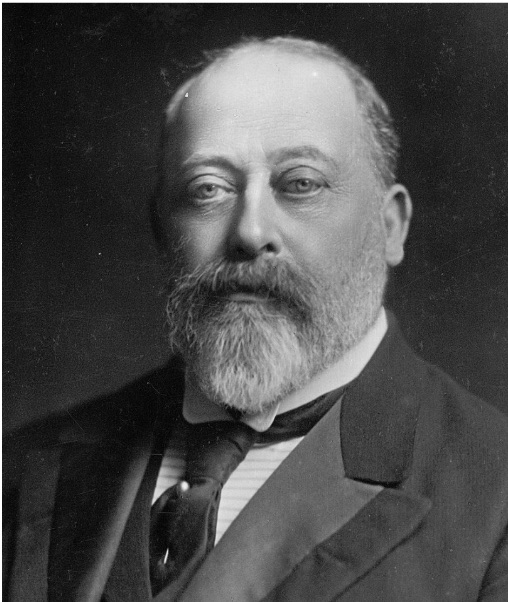

Benjamin Bloomfield (furthest left in the cartoon) was Keeper of the Privy Purse and the private secretary of King George IV (the man in the middle) from 1817 to 1822. Bloomfield’s role as Keeper of the Privy Purse was to manage the king’s spending which had been excessive since his youth; as prince he accrued massive debt for improving, decorating, and furnishing his residencies in London and Brighton (Historic UK). He was also known to spend frivolously on entertainment, his stables, and jewels for his lovers, including Maria Fitzherbert in his youth and Lady Elizabeth Conyngham later on during his regency (Secret history of the court of England, from the accession of George the Third to the death of George the Fourth:, p.301). Below is a portrait of King George IV a few years before the cartoon was published (left) and a portrait of Benjamin Bloomfield (right) in his later years.

National Portrait Gallery; ACD March 2024

In his personal papers, the King wrote that Bloomfield had an “unhappy…& oppressive temper.” There had been tension between the two as Bloomfield tried to restrain the King’s excessive spending and because Lady Elizabeth Conyngham, the King’s mistress, did not like Bloomfield and had ambitions for her own son, Lord Francis Conyngham (man on the right) to take over his responsibilities as Keeper of the Privy Purse. (George IV, p. 218).

the Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon; ACD March 2024

National Portrait Gallery; ACD March 2024

There were also some incidents that led to Bloomfield’s removal. One incident occurred at a theater in which Bloomfield entered and allowed the crowd to believe he was a member of the royal family as they played the national anthem, and these actions insulted the King. Another was when Bloomfield was purchasing diamonds for the King and revealed they were for the King’s mistress, Lady Conyngham (Secret History of the Court of England Volume 2:, p.164).

In the cartoon, King George IV is literally kicking Bloomfield out of his position and the positioning of Lord Francis behind him to take his place with his mother, Lady Conyngham, in the background smiling deviously, is meant to suggest that Lady Conyngham most likely influenced the King’s decision to remove Bloomfield from his position. This cartoon demonstrates how political cartoonists like Cruikshank yielded their cartoons as an effective device to illustrate to the general public what kind of social tensions and controversies were occurring among the nobility and aristocracy during this time. These satirical prints, while meant to be humorous, also acted as a way to get the public to know what went on behind closed doors of political figures and the aristocracy. Most political cartoons throughout England were similar in that they were for humor, but also worked to keep audiences informed on things foreign and domestic. This also became common in America as English cartoons were brought over, and as Americans began creating their own.

Early American Newspapers and Political Satire

Early political satire in America was heavily influenced by English political satire as it served as a unifying force for artists to depict their grievances against British colonialism. Artists like James Gillray were producing cartoons criticizing British military forces, and these would travel to America. Anti-British cartoons grew popular, and Americans began producing similar cartoons themselves.

British Museum; ACD March 2024

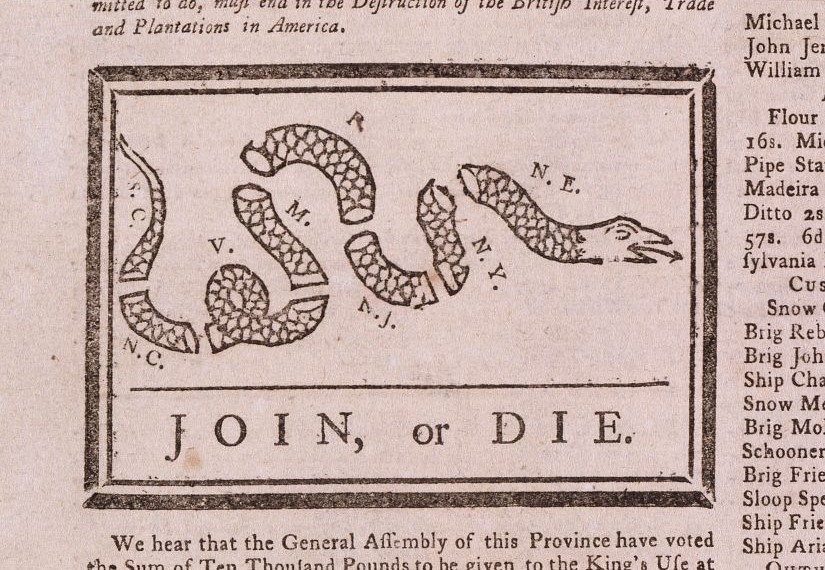

The earliest recorded political cartoon in America is the notorious “Join, or Die” snake cartoon by Benjamin Franklin published in the Pennsylvania Gazette in 1754. The “Join or Die’ cartoon had been used to support unity among colonies during the Seven Years’ War, rather than used for criticisms of specific people or institutions. The snake appeared later during the American Revolution as a symbol of protest against the British government, and again much later during the Civil War. While the “Join or Die” cartoon does not visibly resemble many of the political cartoons of the collection, it had, and still has, immense influence, just as many of the collection’s cartoons had.

The Library of Congress; ACD March 2024

Freedom laws in America were implemented with the ratification of the Bill of Rights in 1791. The Bill of Rights allowed artists and magazines to publish criticisms of political leaders, events, and social issues without retribution. Included in the Bill of Rights was the First Amendment, which guaranteed freedom of speech, religion, assembly, to petition, and of the press. Freedom of the press kept Congress from being able to create laws like ones that had been established in Western Europe to control what was being published. This is what allowed the United States to have so many political cartoonists publishing their opinions and criticisms, even of the government and political leaders.

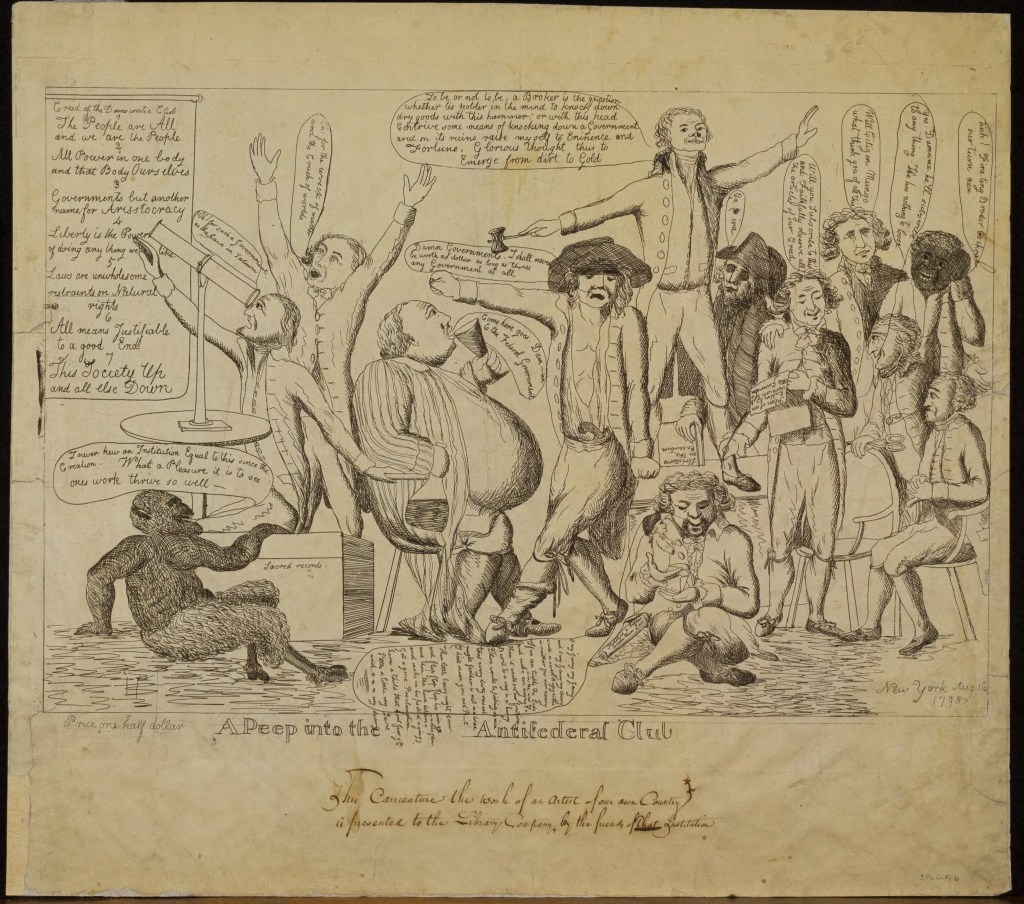

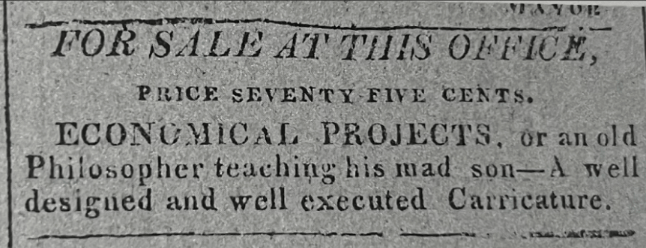

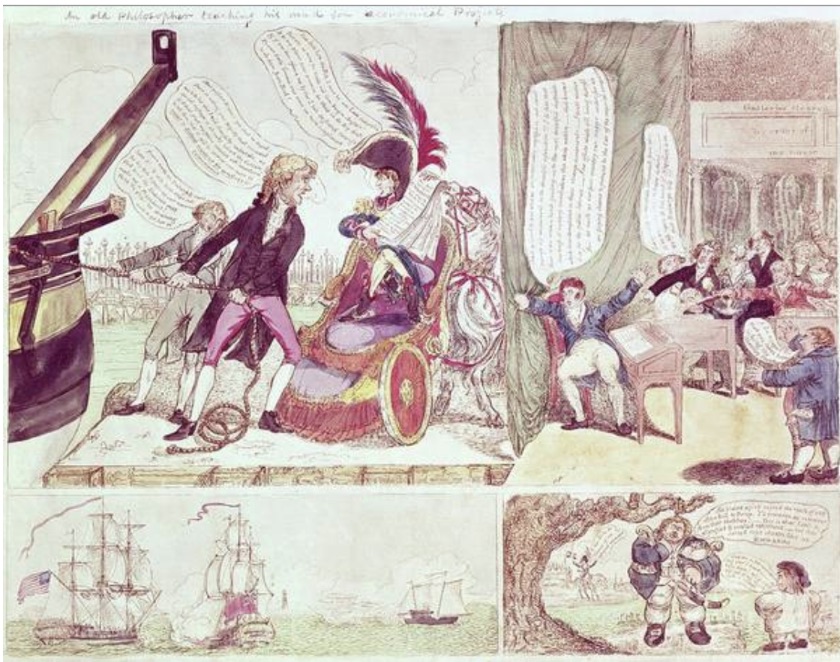

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, United States newspapers displayed advertisements for political cartoons and caricatures to purchase. The artists of these early political cartoons within newspaper advertisements typically did not sign their work and preferred anonymity. Newspapers would publish advertisements selling prints of the cartoon, but not include the art itself. Some examples of these types of papers are the Washington Federalist or Columbian Centinel, that published ads such as “A Peep Into the Antifederal Club” and “Economical Projects” as depicted below. “A Peep Into the Antifederal Club” depicts Democratic-Republican politicians as drunkards conspiring with the devil. “Economic Projects” comments on the Embargo Act of 1807 and shows Thomas Jefferson and James Madison meeting with Napoleon and depicts Congress debating while Americans suffer from the effects of the act.

Despite the fact the newspapers didn’t showcase the art with their advertisements, it’s interesting to see what types of topics within the artwork were being purchased by Americans; people who supported the Federalists may have purchased this cartoon to mock Democratic-Republican politicians they disliked and their policies. Federalist supporters may also find “Economic Projects” humorous because they disagreed with the Embargo Act as well as disliked Jefferson and Madison. People purchased political cartoons that coincided with their political beliefs and would use them to both discuss recent events and for entertainment.

ACD; March 2024

The Library Company of Philadelphia; ACD March 2024

ACD; March 2024

Granger Historical Print Archive; ACD March 2024

In the later part of the eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, there were only about 200 newspapers being published in the United States. However, demand was extremely high for print material and by around 1860, there would be around 300,000 newspapers being published. Newer printing press technology made this possible, and newspaper staff grew exponentially to keep up. Newspapers like The New York Herald only needed 1 or 2 people to write and print a paper, but by 1845, they had 13 editors and reporters, and around 20 compositors (University of Illinois Library, American Newspapers, 1800-1860: City Newspapers). Many of these newspapers also included satirical prints, or advertisements for them. The demand for print material was growing exponentially, and advancements in printmaking would only make it grow more.

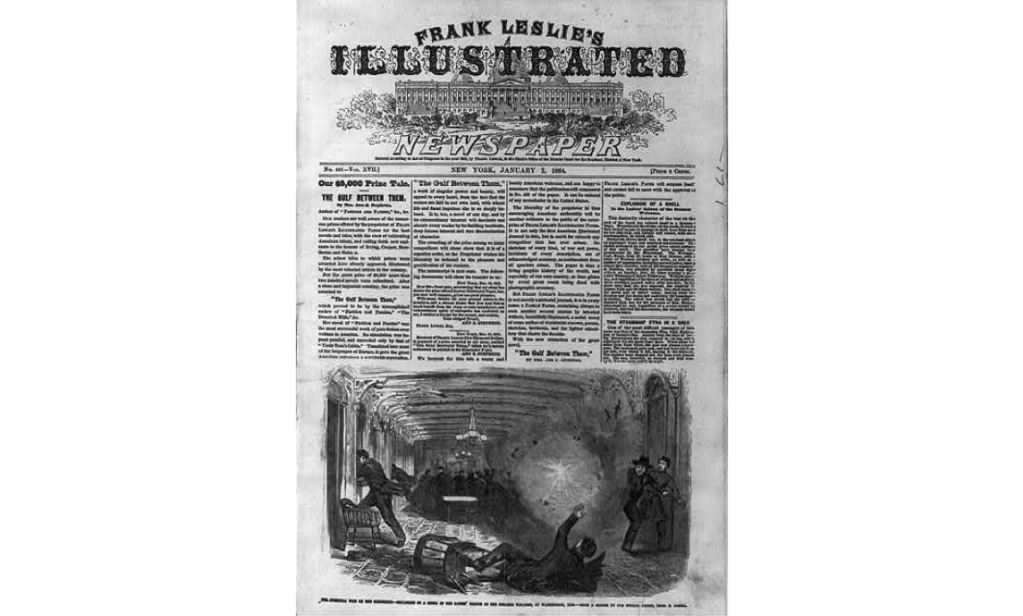

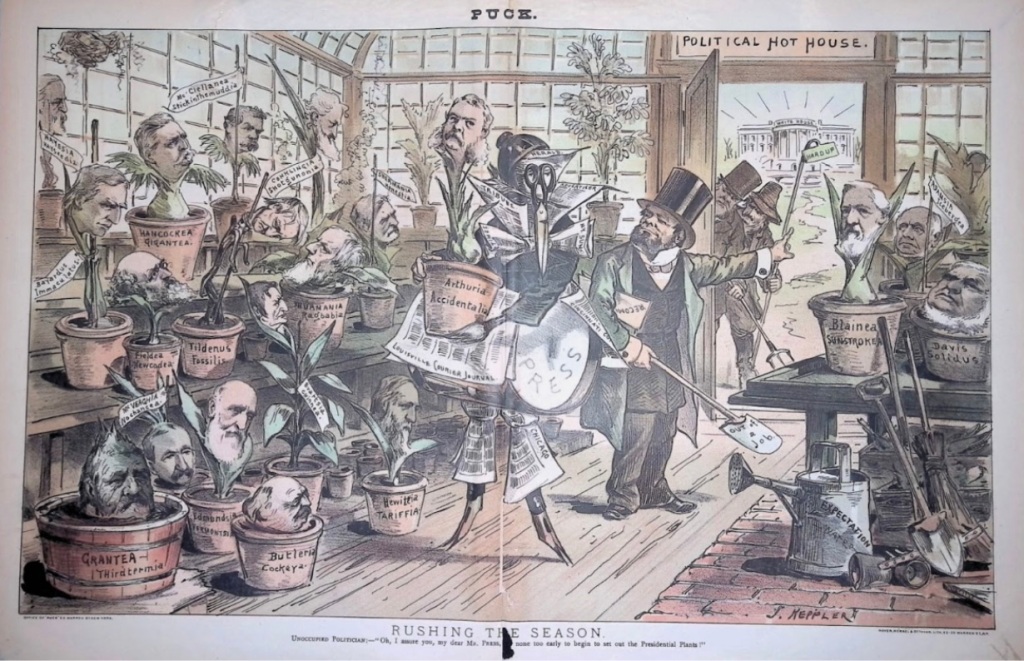

Methods of Printing: The Introduction to Lithography

American political cartoons became more popular at the end of the eighteenth century due to changes in how these illustrations were printed and circulated. New methods would lead magazines specializing in satirical prints to have massive circulation numbers, like Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Magazine that soon after its creation had a circulation of 100,000 that would triple over the course of its run time (Britannica, History of Publishing). Harper’s Weekly would reach approximately 160,000 subscribers after the Civil War (Mott’s A History of American Magazines; p.476). And illustrated magazines like Puck and Judge who came later to the satire publishing scene, by the 1890s through the 1900s, both had soaring circulation stats of 90,000 (Puck) and 100,000 (Judge) (Theodore Roosevelt Center; American political humor : masters of satire and their impact on U.S. policy and culture).

In 1796, the method of lithography printing was invented, and soon more cartoonists were publishing lithographs instead of engravings or etchings. Engravings originated in the 15th century in Germany. With this method, the printmaker uses a very sharp metal tool called a burin to carve into a metal plate, then it is covered in ink and placed on a press with paper and the image is transferred. Since this method requires precision and strength from the printmaker, it was somewhat costly. In addition to this, prints could not be made in color. As for etching, which originated in 16th century Germany, a metal plate is covered in a varnish or wax and then an etching needle is used to scrape the image exposing the metal below. The plate is then put in acid to eat away the exposed metal, and covered in ink and transferred onto paper through a press. Similar to engraving, the method of etching took much time and could not be done in color. This is why once lithography was introduced, many caricature artists would prefer this method.

Vault Editions; ACD March 2024

Lithography was done by the design being drawn onto limestone with an oil based crayon or ink, then a layer of powdered rosin and talc is rubbed onto the stone. After this, gum arabic is brushed onto the stone and lithotine is used to wipe away the original drawing. Then asphaltum is buffed into the stone to provide a better base for ink, the stone is brushed with water, then ink is rolled onto it, and finally the image is pressed onto paper. For colored images, the process is repeated for individual colors. In addition to being able to produce colored images, the method of lithography offered room for more detail in images. Although this method has more steps than etching or engraving, the process of creating lithographs was able to run much smoother in a printing workshop. This also allowed for art to be printed faster and in larger quantities, exposing more people to caricatures than had before. It was because of this efficient production and visually striking printing method that gave rise to magazines specializing in art, and, more specifically, visual satire.

American Illustrated Magazines: Frank Leslie’s and Harper’s Weekly

One of the first established American illustrated magazines was Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, started in 1855. Although this magazine is not included in the collection, many cartoonists who later joined the publications that are within this collection mentioned that they had gotten their start at Frank Leslie’s.

Frank Leslie, otherwise known as Henry Carter, was born in England and found himself interested in art and engraving at a young age. His family discouraged him, so he sent his work to the Illustrated London News secretly under the pseudonym Frank Leslie. He moved to the United States at 27 and worked for some newspapers as well as attempting to start a few of his own. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, however, seemed to be the one that stuck and was favored by audiences. This newspaper seemed to spark a trend of political cartoon publications and remained popular until its end in 1922.

Suffolk Artists; ACD March 2024

Library of Congress; ACD March 2024

Another early American political cartoon magazine that had influence on later publications was Harper’s Weekly which started in 1857. American Brothers James, John, Fletcher, and Joseph Harper created a publishing company called Harper & Brothers in 1833 and began printing their own magazine, Harper’s Magazine in 1850.

It included political cartoons, as well as works from well-known authors like Charles Dickens. After seeing the success of this publication, Fletcher Harper decided to create another magazine, but one that would be published weekly featuring satirical cartoons and news called Harper’s Weekly. Since the company was already fairly well known, the magazine was a quick success.

HathiTrust; ACD March 2024

Hathi Trust; ACD March 2024

Archive.org; ACD March 2024

Harper’s Weekly was known for their coverage of the Civil War and advocating for abolition. Prior to the Civil War, Harper’s Weekly did not discuss anything too controversial and did not show partisan preference, however once the Civil War started, they quickly took a Republican stance and supported the Union army. One of their most well known articles was on an escaped slave serving in the Union army they called “Gordon.” They included an illustration of the scars on his back from being whipped. Generally, Harper’s Weekly showed support for the Union, and showed people in northern states the truth of the brutality slaves experienced in the South. They encouraged people to join the cause and fight with the Union army. Frank Leslie’s also covered the Civil War, but focused more on news events than broader stories like Harper’s Weekly did. Frank Leslie’s was also marketed towards people in the North as a way to better visualize what was happening during the war and in the South specifically.

During and following the Civil War there was a quick growth in popularity for Harper’s Weekly and the other illustrated magazines that were covering the war. These magazines also gained recognition for their literary aspects as well. Harper’s Weekly specifically would include short stories and an illustration to go along with it. They also included articles on social events with illustrations.

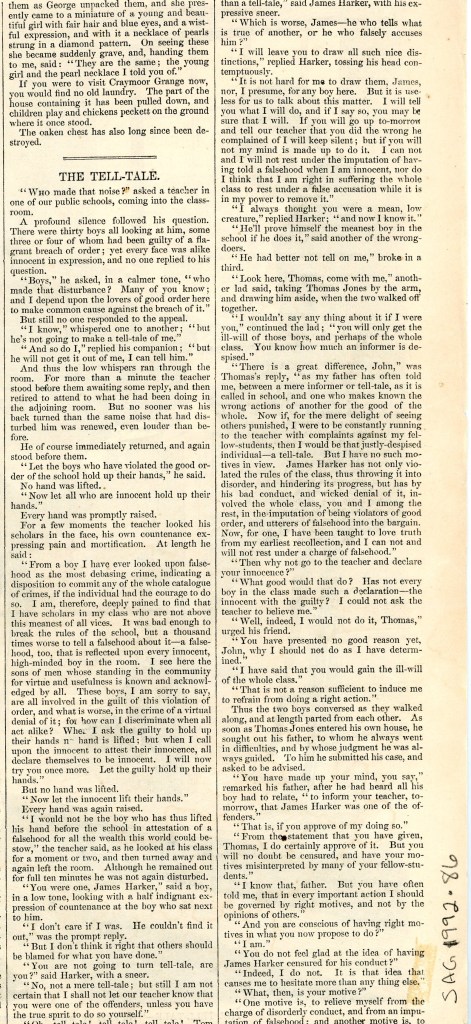

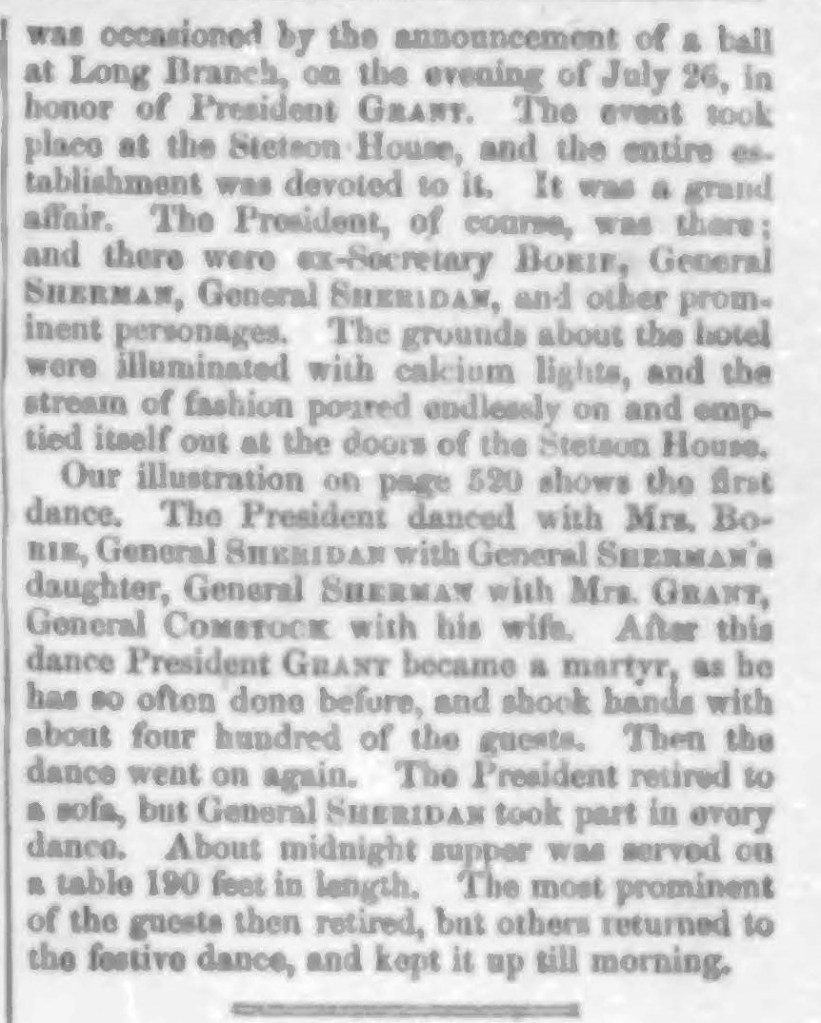

Two examples are included below, one is titled “The Tell-Tale” that is an illustration of a short fictional story provided on the back of the picture, and another is an article covering a presidential ball and includes an illustration of the event.

“The Tell-Tale” by an unnamed artist shows a school-boy handing his teacher a note. The story that goes along with the illustration tells of a school-boy who was struggling with himself over whether to tell the truth or not, fearing that his peers will see him as a “tell-tale.” The story does not name specific people or events, but is an entertaining story that may also be seen as presenting a lesson about truth telling.

The other cartoon, “Grand Ball Given in Honor of President Grant at the Stetson House,” by C.G. Bush in August 1869. This illustration depicts a ballroom scene at the Stetson House in New Jersey that was hosted by Ulysses S. Grant. The Stetson House was built by John B. and Elizabeth Stetson in 1886. The Stetsons had purchased the land from Henry A. DeLand to support the school DeLand had founded. The family used it as a winter house, and on the weekends, the Stetsons hosted many guests like Ulysses S. Grant, the Vanderbilts, Grover Cleveland, and the Prince of Wales. They also hosted parties like President Ulysses S. Grant’s presidential balls (West Volusia Historical Society).

The illustration shows people dancing and the story mentions the events of the night and the overall fun everyone had at the ball. I think it’s very interesting to see press coverage of early presidential balls. The location, attendees, and dress of these balls shift overtime, and this one stands out to me as it seems to be more of a regularly occurring party for fun, than a grand event for publicity. In fact, the Stetsons were known to invite the Leland Municipal Band every weekend to their home to perform a concert for family and friends, including political leaders and influential families. More modern presidential balls appear as more of a formal performance and procession, and only happen during a president’s inauguration. This ball, however, does not seem to be for Grant’s inauguration or a specific special occasion. It shows political and societal themes of the time, and the range that Harper’s Weekly had.

The Golden Age of Political Cartoons

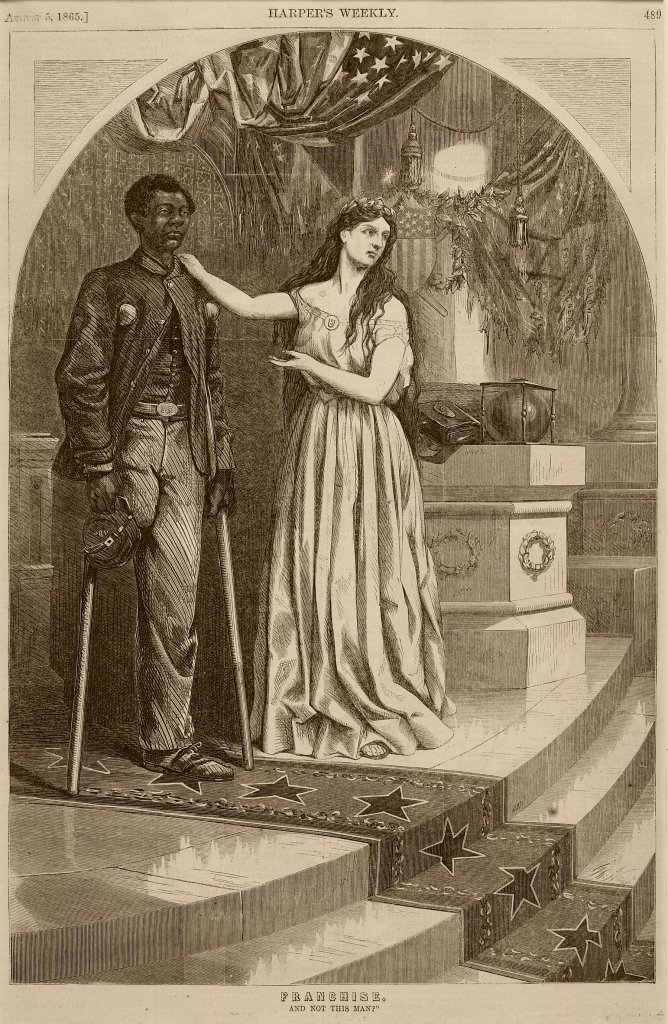

In addition to including social caricature and illustrated stories, illustrated humor magazines may have grown so much after the Civil War because of the rapidly changing political and social spheres in the United States influencing the cartoons they included. Magazines had a surplus of information to report on and to caricature due to the changes of the Reconstruction Era, through the Gilded Age, and into the beginning of the Progressive Era. The Reconstruction Era brought major changes. For one, the challenge of rebuilding the South, both literally and figuratively as the war had destroyed and burned homes, bridges, fields, and other types of infrastructure as well as the new implications of enforcing the 13th amendment. Despite slavery being abolished, the United States government did not protect and support newly emancipated Black Americans from going back to work on plantations to make a living. There were also struggles for Black Americans politically and socially in the South, as well as struggles in being accepted in the North. This era also had many white supremacy groups appearing as a retaliation against Reconstruction.

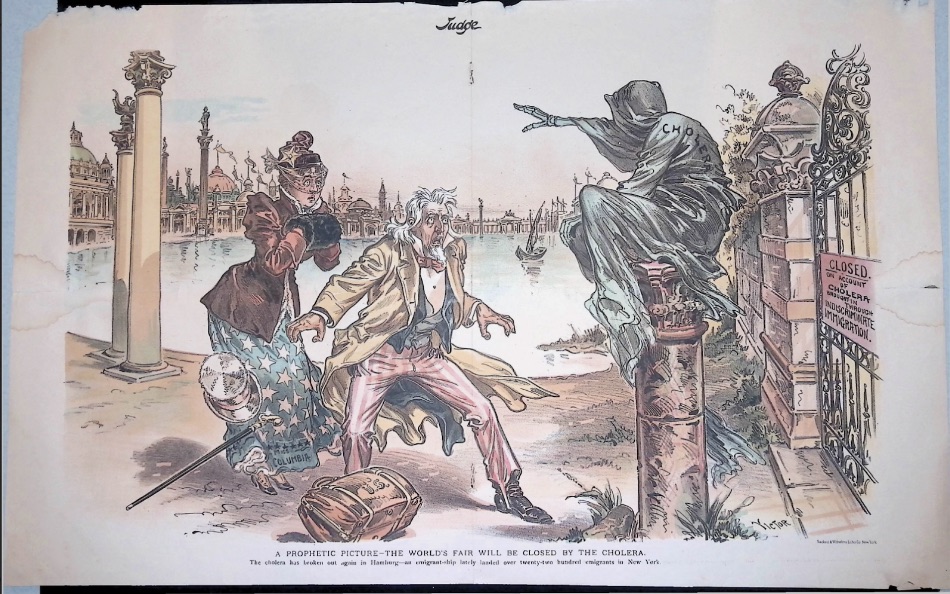

There was also rapid industrial growth as the United States experienced an industrial revolution with the expansion of railroads being built across the country. With this railroad expansion, many Americans migrated further west, seeking new opportunities, land, and gold. There was a massive influx of immigrants coming into the country from China, Ireland, Italy, and parts of Eastern Europe. The United States faced numerous political debates on how to handle these issues like currency, immigration, voting laws, and labor laws.

So it comes as no surprise that the rapid changes occurring across multiple sectors of American society created many challenges for Americans during this time period. These challenges provided ample material for artists to address them within their cartoons which made illustration humor magazines even more popular as it was a way for the public to face these societal issues in a humorous way. The apparent success, quantity, and popularity of cartoons being produced during this time came to be known as the “golden age” of political cartoons.

Thomas Nast’s View of Reconstruction

Harper’s Weekly magazine was just one of many illustrated magazines that employed talented artists to address these issues. They featured artists such as A.B. Frost, Charles G. Bush, William L. Sheppard, Winslow Homer, Livingston Hopkins, and possibly the most well known was Thomas Nast.

Wikipedia; ACD March 2024

Thomas Nast was a cartoonist born in Germany, but moved to New York for schooling as a young boy. He took an interest in art and began studying under American artists, and later attended art school. While he was far from being the first American cartoonist, his work held great influence in American politics earning him his title as the “father of the American cartoon” (Florida Center for Instructional Technology, Thomas Nast). Nast originally worked for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, but did not have his own work published in the newspaper. Some of his work began appearing in Harper’s Weekly in 1859, but he soon went to London where he briefly worked for The Illustrated London News and Vanity Fair.

He returned to New York and Frank Leslie’s for a period of time before becoming a full time staff member at Harper’s Weekly in 1862. Nast popularized many political symbols during this era such as the Republican elephant, Democratic donkey, and Columbia. He is also known for being the creator of the modern Santa Clause depiction. The magazine itself already had a large following, but Nast’s memorable work especially made the magazine very popular. His work on Harper’s Weekly is remembered as one of the most influential in the United States during his lifetime.

Thomas Nast’s political views aligned with that of the Republican party for most of his career. The Republican party developed out of being strongly opposed to the expansion of slavery in the western states and a desire to modernize socially and economically. Republicans valued free market labor and placed an emphasis on social mobility. They originated from being opposed to the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which opened up Kansas and Nebraska to be admitted as slave states and eventually became the party that had wanted to abolish slavery (Norwich University, Major American Political Parties of the 19th Century). The original party members consisted of ex-Whigs and ex-Democratic-Republicans who disagreed with aspects of their own parties, and free-soilers. Republican members and supporters were also typically Protestants who opposed Irish Catholic immigration, farmers, urban workingmen, and freed African Americans (The Origins of the Republican, 1852-1856; p. 426-439).

Republicans also supported a national bank, the gold standard, railroads, and there was a divide within the party on the topic of slavery; some Republicans in the nineteenth century were opposed to the expansion of slavery, but did not support abolition and considered those who did within their party to be “radicals” (American Battlefield Trust, The Radical Republicans).

The values and goals of the Republican party changed vastly following the twentieth century, and ideologies of the modern Republican party are closer to those of the Democratic Party prior to the twentieth century, which believed that Congress had no authority over states rights (which at that time meant the right to own slaves) and that the federal government’s power should be limited. 19th century Democrats were also anti-national bank and would later support the free silver movement (UC Santa Barbara, 1856 Democratic Party Platform). Both Nast and Harper’s Weekly as a whole commonly supported the Republican side politically, which is reflected in the cartoons and articles that would appear in the magazine.

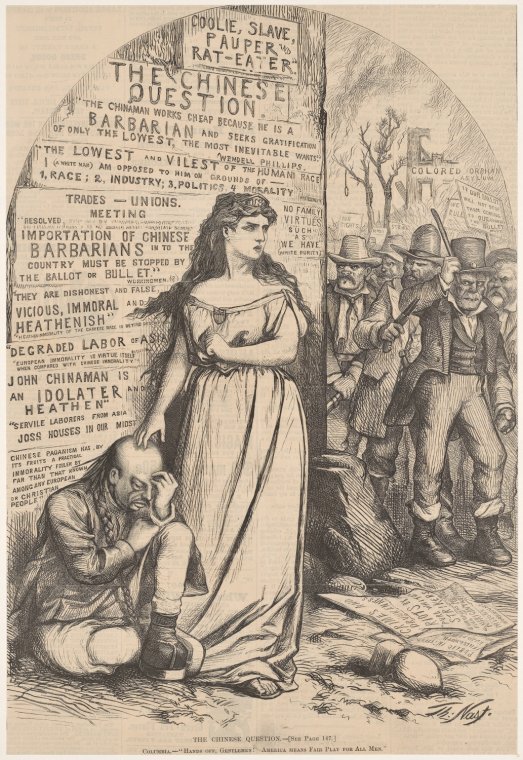

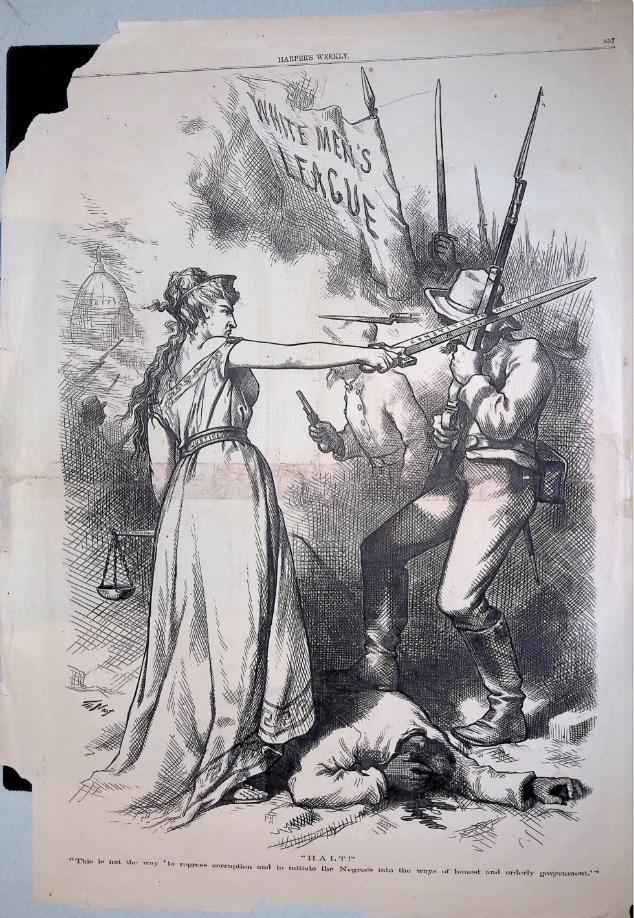

Nast was considered to be a “Radical Republican” who was strongly opposed to slavery and Black emancipation (Ohio State University, Thomas Nast, 1840-1902), and like most Republicans at the time he was a staunch Protestant who strongly opposed Irish immigration due to his anti-Catholic beliefs (Thomas Nast: The Father of Modern Political Cartoons; p.33).