Wilkes University Archives is excited to announce that thanks to Kaycee Wren, a Junior History and Secondary Education Major, the Wyoming Valley, Wilkes-Barre, and Luzerne County General subseries of the Gilbert Stuart McClintock collection is now processed and digitized.

Along with working in the archives, Kaycee is in both the Honors and Barre Scholars program and occasionally attends events and meetings for the Education club. Kaycee aspires to become a History Teacher and eventually go on to receive a PhD in History. Outside of Wilkes University, Kaycee enjoys painting, crocheting and traveling.

Jessica Van Orden, a Creative Writing Grad Student, has aided in the transcriptions and in writing the blog post.

The finding aid can be found here. The finding aid and blog post have been supervised and edited by Suzanna Calev, Wilkes University Archivist. Below are Kaycee and Jessica’s reflections.

The Wyoming Valley, Wilkes Barre, and Luzerne County subseries within the Gilbert Stuart McClintock Special Collection consists of manuscripts, notes, lists, notices, meeting minutes, decrees, ledgers, letters, certificates, newspaper clipping, and memorandums written and created by various historical figures who made significant contributions to the establishment of Wilkes-Barre, Luzerne County, and the Wyoming Valley.

The materials in this collection were donated to Wilkes by Board of Trustees member Gilbert Stuart McClintock in 1959. Gilbert Stuart McClintock [1886-1959] was a prominent figure in Wilkes-Barre, gaining the nickname “Mr. Wilkes-Barre” and became a major stakeholder in the Glen Alden Coal Company. McClintock was active in politics, working in the civil rights movement and becoming an early supporter of the ACLU [American Civil Liberties Union]. In 1938, he was appointed the first chair of the Wilkes Board of Trustees. He devoted a lot of his time to Wilkes College and always tried to expand what the college did. Upon his death he donated his wealth to increase the salary of Wilkes Faculty.

The materials focus on a wide range of events and affairs that touch upon topics such as the Susquehanna Company, the Battle of Wyoming, the French Azilum, the Sullivan Expedition and the Centre Turnpike and Eastern and Wilkes-Barre turnpike road. The manuscripts contain fascinating insight on the development of the areas listed above, but also what life looked like for earlier settlers, how they managed their political affairs day to day, and the aftermath of the American Revolution and the interstate wars that occurred between Connecticut and Pennsylvania at the end of the eighteenth century. To view specific manuscripts that directly discuss various aspects of the Pennamite-Yankee wars, please visit the Susquehanna Claim subseries here.

It is the emphasis on community development that truly stood out among the collection in its entirety. From the earliest manuscripts which feature meeting minutes that delineated the creation of vital infrastructure, the development of the rule of law within the valley that instigated negotiations of peace, or even the creation of a refugee community amidst the strife and violence of the French Revolution, the importance of community above all else rings loudest. With a region stretching over reaching mountains and numerous rivers, it is not surprising that the residents of the rural valley realized the strength of collaboration.

Yet, to accomplish any of the great accomplishments seen within the collection, it makes sense that our earliest manuscripts are those establishing the settlements themselves.

Settling the Area: The Susquehanna Company and Forming a Government

One of the major challenges for earlier Connecticut settlers in the Wyoming Valley was establishing and maintaining a form of government and law. This is not surprising as King Charles II granted the same land to colonies of both Connecticut and Pennsylvania, resulting in years of suffering and bloodshed for settlers attempting to settle along the Susquehanna River. The first Connecticut settlers who came to Pennsylvania after hearing words of ‘fertile soil and prosperity’ fell into many hardships. As you could imagine, Pennsylvania settlers were unhappy that outsiders were encroaching on their land. This led to various arrests of Connecticut settlers, and eventually skirmishes which turned into the Pennamite and Yankee Wars. During this early time period, settlers negotiated and focused on ways to survive in this new territory amidst violence and uncertainty.

We also see how different approaches were being taken by the companies settling the areas, such as the Susquehanna Company, as they attempted to meet the needs of their developing towns and governments. It was not until 1772, a time of peace before the Second Pennamite War, when Pennsylvania and Connecticut settlers started to establish a form of government and a comprehensive law within their respective townships. In 1772, the borough of Wilkes-Barre was laid out and Fort Wyoming was adjoined. As more and more settlers moved to the various establishments along the Susquehanna River, a sense of community began to arise. When difficulties arose in regards to land rights, town committees were formed and during the committee meetings is where these disputes were resolved.

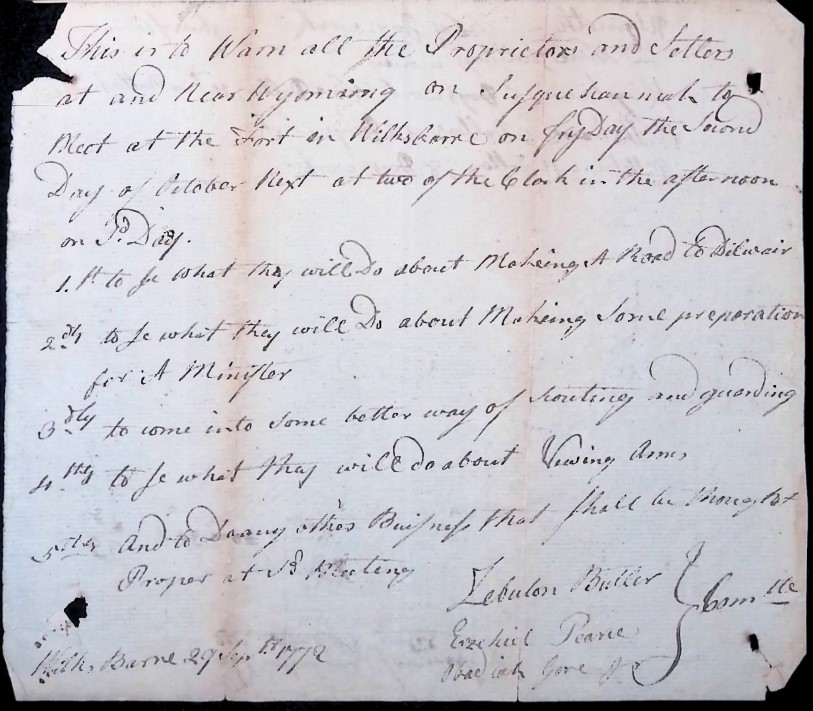

This brings us to Wyoming Valley, Wilkes-Barre, Luzerne County General Subseries. Having the privilege of researching and sitting with various contents from this time period has opened my eyes to what life was like for early settlers, and more importantly the establishment of order and government with town committees, which I found fascinating. One item that displays this early process by the company is 12.53 item 7a, which depicts a notice by Zebulon Butler regarding an upcoming meeting for the subscribers and proprietors of the Susquehanna company claims.

12. 53 Item 7a: Notice by Zebulon Butler et al., 1772 September 29.

This is to Warn all the Proprietors and Setlers [sic] at and Near Wyoming on Susquehannah to meet at the Fort in Wilkesbarre on FryDay [sic] the Second Day of October next at two of the clock in the afternoon on s.d [sic] [said] Day.

1.st to se what they will Do about Makeing [sic] a Road to Dilvair [sic] [deliver]

2.dly to se what they will Do about Makeing [sic] some preparation for A Minister

3.dly to come into some better way of scouting and guarding

4thly to se what they will do about Vewing [sic] Arms

5thly and to Do any other Business that shall be thought Proper at s.d [sic] [said] Meeting.

Zebulon Butler }

Wilkes Barre 29 Sept 1772 Ezekiel Pearce } Comtte

Obadiah Gore Jr }

We see how the company is attempting to settle some normalcy within the people, not only with the creation of infrastructure and roads that ease travel, but hiring a minister for services and establishing a guard who would oversee the perimeters. These early motions highlight how the communities were approached in settling the land once the people were transported from Connecticut to the Wyoming Valley. It was a multilayered process where the benefits of the settlement had to meet the expectations of those immigrating to this new region in hopes of finding opportunity within it, not conflict.

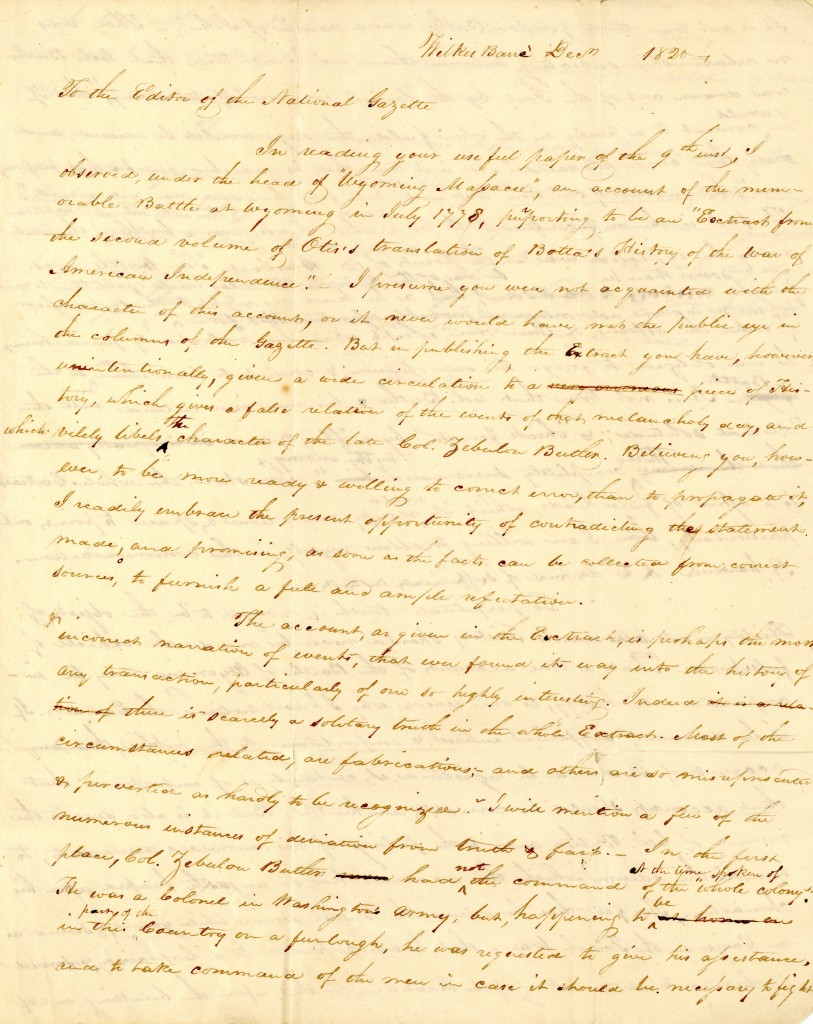

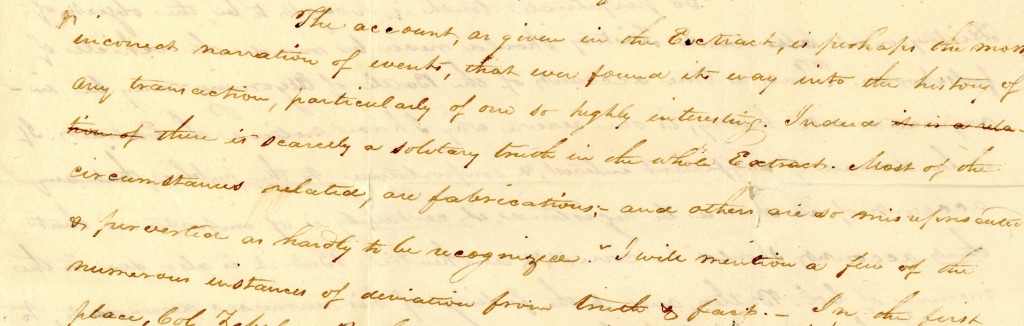

Zebulon Butler is a prominent figure of Connecticut during this period. Butler was an American military officer who served as a Connecticut leader within the Yankee-Pennamite Wars, and later as the director of the Susquehanna Company from the 1750s through the 1760s, as well as the Revolutionary War within the Continental Army.

Revolutionary War Journal; ACD May 2024

He is most notably remembered for his command over the devastating loss against British forces in the Battle of Wyoming. However, he proved to be a powerful political voice, playing a decisive role in the brewing conflict amid the Susquehanna Controversy, as he represented the Wyoming Valley during the Connecticut Assembly. He later went on to speak avidly for peace, assisting Timothy Pickering in counseling peace between Pennsylvanian and Connecticut settlers and the establishment of Luzerne County.

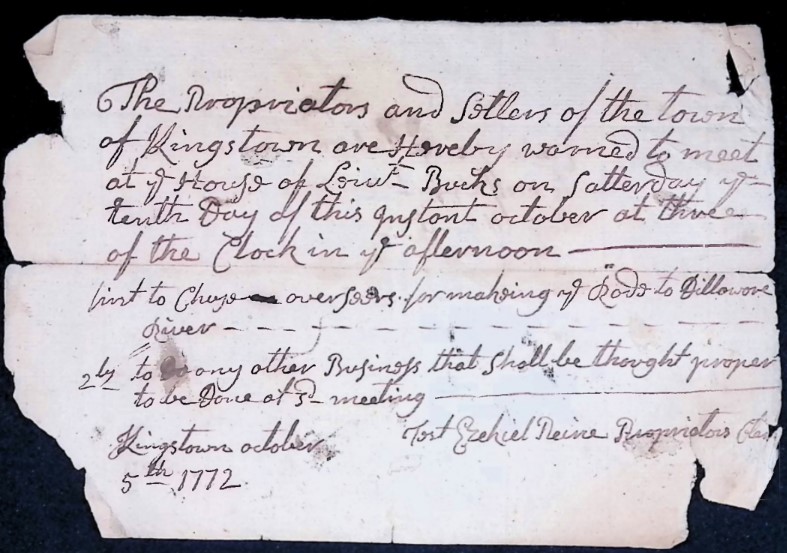

Other topics often discussed in these committee meetings included developing upon the relations and building already within the valley. These could be making alterations or developing roads, disputing land deeds, and the development of new businesses, as well as fortifications. Let’s take a look at another early meeting notice written by Ezekiel Pierce and Nathan Dennison on the 7th of September, 1772.

12. 51 Item 5: Notice by Ezekiel Pierce and Nathan Dennison, 1772

These are to Warn all the Propriators Belonging to the town of Kingstown [sic] to meet at the House of Thomas Bennets Where ye old Fort once stood on Saturday the 12th Day of this Instant September at one of ye Clock in ye afternoon.

1st to Chuse a Comtee [sic] [committee] to transact town affairs & c:

2ly to se if ye town will make any alteration in any of ye Roads in sd [sic] [said] town and Lay out a New Road or Roads.

3ly to se if ye town will give a piece of Common Land to Peter Harris joyning [sic] to his Land for ye strip of Land that was taken of from sd [sic] [said] Harris & meadow Lott in order to Commode ye town Lotts or settle with sd [sic] [said] Harris some other way &:

4ly to se what ye town will do in Building a fortification & to act upon any other Business that shall be thought proper

Kingstown September Ezekiel Pierce Clerk-

the 7th 1772. Nathan Dennison

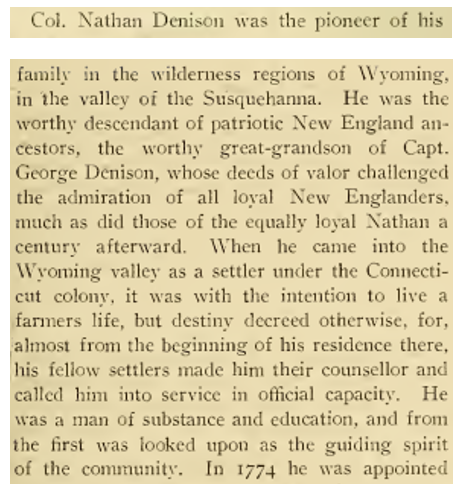

Nathan Dennison was one of the first forty shareholders in the Susquehanna Company. Dennison was a justice of the peace for Luzerne County from 1774 to 1778, and from 1776 to 1780 he was a member of the Connecticut assembly. Dennison also had a military career being appointed in May 1775 as lieutenant colonel of the 24th Regiment of Connecticut militia, and two years later in May 1777 he was promoted to Colonel. Dennison took an active role in the community and establishment of the Luzerne Valley.

Genealogical and family history of the Wyoming and Lackawanna Valleys, Pennsylvania. Higginson Book Co.

Wikimedia; ACD May 2024

Transcription:

“Col. Nathan Denison was the pioneer of his family in the wilderness regions of Wyoming, in the valley of the Susquehanna. He was the worthy descendant of patriotic New England ancestors, the worthy great-grandson of Capt. George Denison, whose deeds of valor challenged the admiration of all loyal New Englanders, much as did those of equally loyal Nathan a century afterward. When he came into the Wyoming Valley as a settler under the Connecticut colony, it was with the intention to live a farmer’s life, but destiny decreed otherwise, for, almost from the beginning of his residency there, his fellow settlers made him their counsellor and called him into service in official capacity. He was a man of substance and education, and from the first was looked upon as the guiding spirit of the community.”

Major Ezekiel Pierce was one of the ready writers of the early days spending years as a town clerk. To no surprise, many of the town’s remaining documents are in his handwriting. He was town clerk of Plainfield, Connecticut from 1749 to 1754 along with Wyoming. Pierce was a Captain in the 11th Regiment Connecticut militia until he was promoted to Major in October 1758. Pierce was one of the original members of the Susquehanna Company and one of the origins, settlers at Wyoming in 1762. He was elected Proprietors Clerk of the settlement and performed duties under that title until the organization of the town of Westmoreland in March. 1774, when he was elected Town Clerk and Recorder of Deeds in and for the new town.

The meeting notice above was directed to the proprietors of Kingstown, requesting their attendance at a meeting to be held at Thomas Bennet’s house, located where the old forty fort once stood. The agenda for the meeting included several items such as the election of a committee to oversee town affairs; secondly; discussion regarding potential alterations to existing roads and the possibility of establishing new ones; thirdly, deliberation on the proportion of granting a piece common land to Peter Harris, consideration of plans for constructing a fortification, as well as any other matter deemed relevant by attendees.

By examining notices like the one above it places you in the shoes of the founders of the Wyoming Valley. Most fascinating is how the basis of our government today is sitting right in front of you. While it may be peculiar to us today, the concept of crucial town decisions being deliberated in someone’s dining room highlights the early development of our local government. If it was not for the early settlers’ great sense of civic duty, who is to say that we would be as organized and developed as we are today?

Early Mercantile Development and Indigenous/Settler Conflicts

Even as those governments were being established, though, there is a robust history living within the valley floor. Although the settlers were finding places to plant their name and building up their own settlements, they were often rural and difficult to travel. Moreover, there was already a rich network of indigenous communities who understood the land and how to navigate it while the settlers were still learning to walk among it.

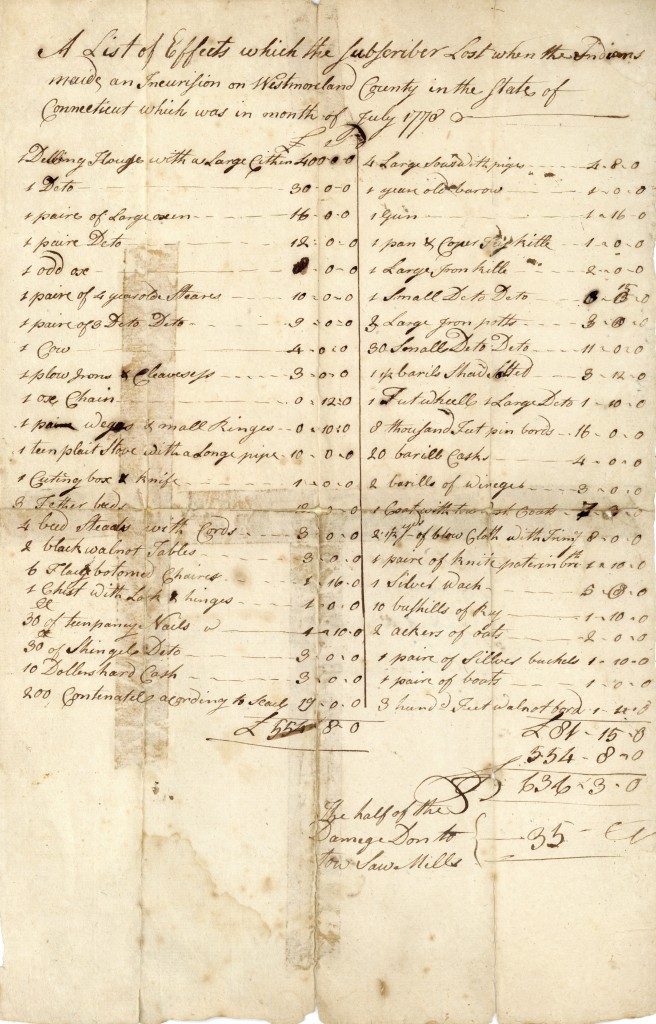

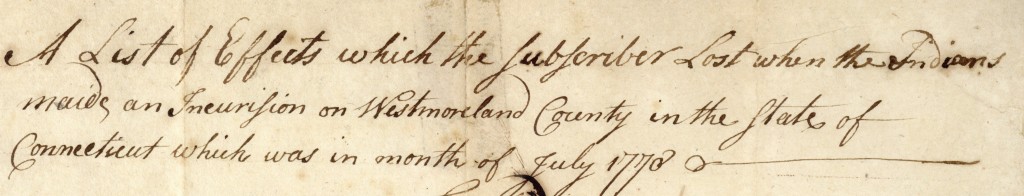

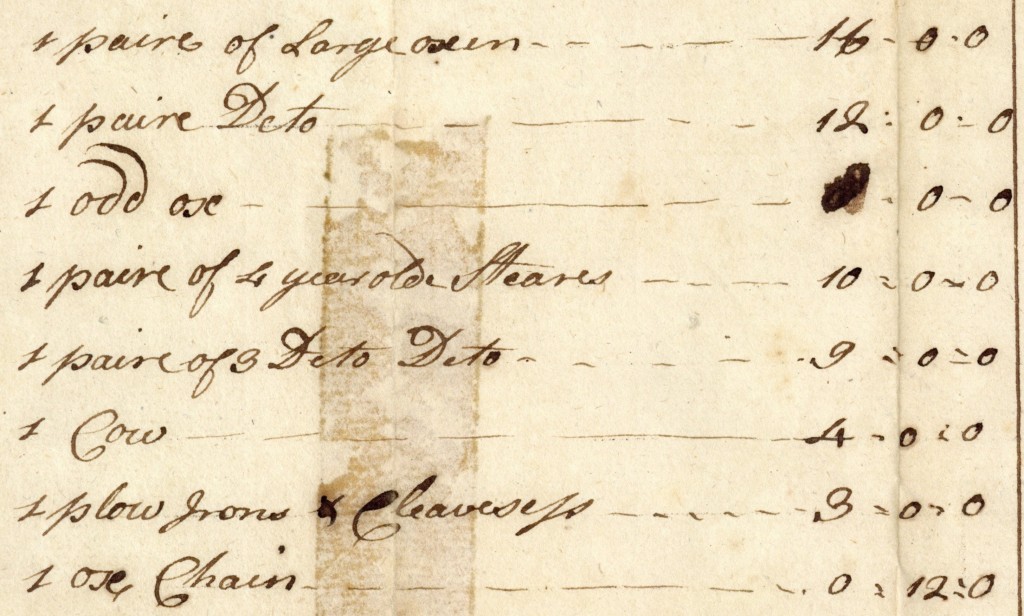

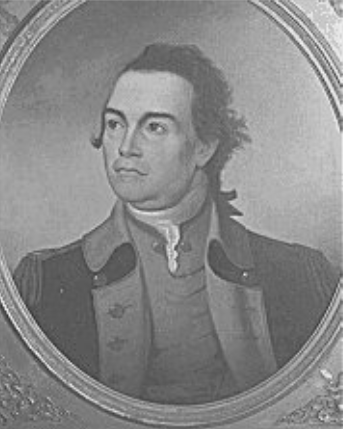

12. 50 Item 4: List by Matthias and John Hollenback, 1770 July.

The manuscript depicts a list of items, written by Matthias and his father, John Hollenback (1720-1793). The list denotes a number of items that were lost in the settlement when indigenous tribes attacked a shipment. At the time when this list was created Matthias Hollenback was establishing himself in Wyoming Valley after moving there in hopes of making an entrepreneurial name for himself and settling under the Connecticut claim.

Chemung History; ACD May 2024

He left his birth place in 1769 with only his horse, the clothes on his back and fifty dollars. Hollenback was successful in business and trading, while also serving in the army during the Revolutionary War. He solidified himself in trade through his various shops along the Susquehanna river,most notably his affairs at Tioga Point. Near the end of his life Matthias Hollenback served honorably as a Judge and continued to contribute greatly to the establishment of the Wyoming Valley through investments.

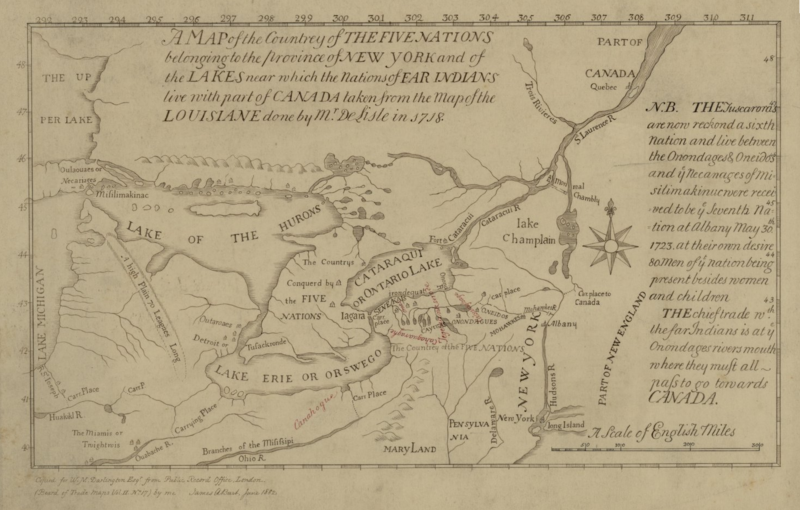

The Susquehanna river was a powerful source for the early settlers of the Wyoming valley, as it opened up routes not only for transportation but hunting and fishing. Many settler communities established forts along the river in both directions. One of these prominent tributaries was the Chemung river, which Hollenback took an avid interest in for its accessibility to multiple colonies, such as the Genesee region. The region had already been inhabited by the Algonquin, Andaste, Delaware and Seneca communities, however, the indigenous developed alliances with british loyalists during the American Revolution which led to numerous conflicts with the early settlers (Chemung County).

Chemung River Friends; ACD May 2024

Following the American Revolutionary War, Hollenback opened up numerous trade posts along the Chemung river in order to access and transport goods and resources both in and out of the rural Wyoming valley by neighboring cities, but there is evidence that his ventures began even before these larger establishments (Chemung County).

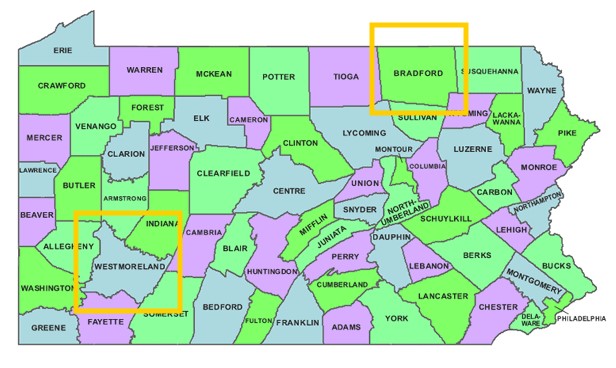

In this manuscript, Hollenback notes that the items being transported were lost by settlers living in Westmorland county, nearly on the opposite side of the state.

University of Pittsburgh; ACD May 2024

This demonstrates how Hollenback may have been trying to begin this trade early on, but the isolated aspects of Westmoreland made the incursions more likely to succeed. What is interesting about the manuscript is that it demonstrates an early form of insurance regarding the possessions of the settlers. They have compiled a list of items that range from livestock, with oxen, cows, and even aged steers, to tools and materials, such as Irons, Chains, and Plow Clevises.

These tools would have been necessities for the ways of life, cultivating land and food sources for those in the valley, and Hollenback’s record of those losses demonstrates how those in positions of power could advocate for the people of these developing communities.

WorthPoint; ACD May 2024

West Virginia University; ACD May 2024

It also shows how the settlers’ dependence on a foreign terrain in these early days left them vulnerable to a conflict that was brewing between the indigenous populations as well as the one they were bringing to the English. However, Hollenback’s business within the valley would adapt to build relations not only between the counties following the revolutionary war, but the indigenous communities that they lived amongst.

Hollenback would frequently trade and sell with various tribes nearby, creating an easy network with a principal store in Wilkes Barre and branch posts in Tioga Point and Newtown. The most popular items transported on this route were “guns, gunpowder, blankets, cloth, liquor, and flour,” and Hollenback became a popular source of goods not only for the settlers in the valley but the neighboring tribes (Chemung County). He became a confidant and trusted man among them, often being invited to treaties that would come in the years to follow (Chemung County).

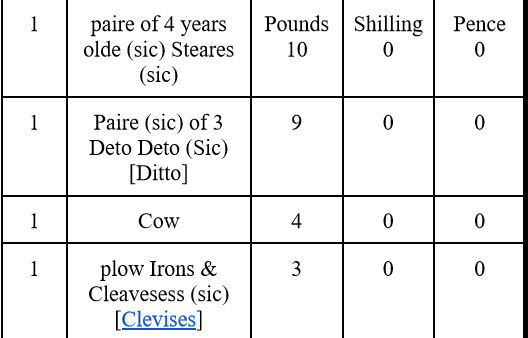

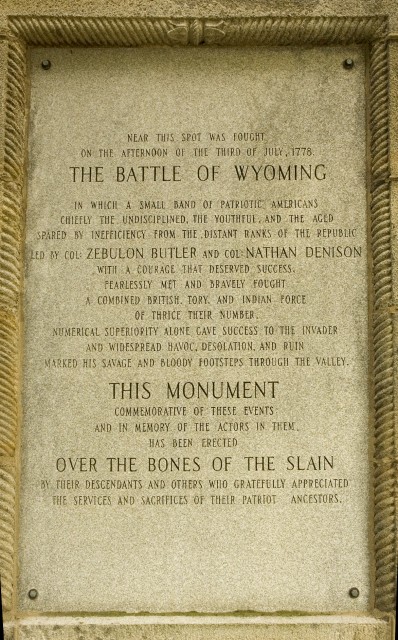

While individual peace relations were being established in the valley, there were a number of people who remembered the Iroquois Confederacy’s alliances with Britain and its loyalists on the ground. There were many contentious debates following one of the largest massacres in the valley, The Battle of Wyoming, where the Iroqouis warriors joined a loyalist militia headed by captain John Butler. The militia descended into the valley on July 3, 1778, killing over three hundred settlers, many of whom were women and children, and destroying the settlement.

Library of Congress; ACD May 2024

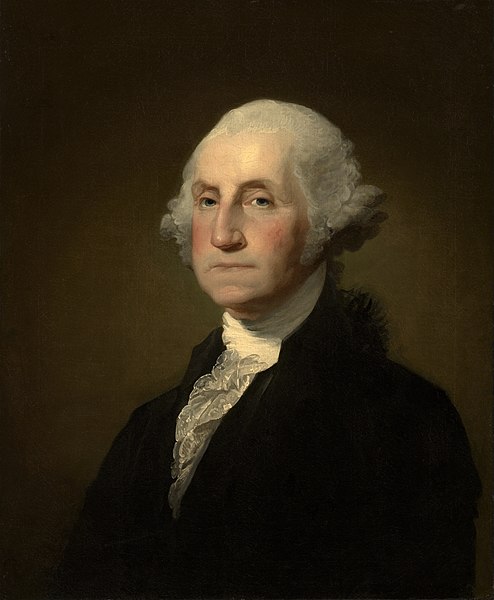

In the years following the revolutionary war, George Washington would respond to the continued conflict between settlers and the Iroquois Confederacy with brute force by which the valley had not seen: the Sullivan Expedition.

The Sullivan Expedition

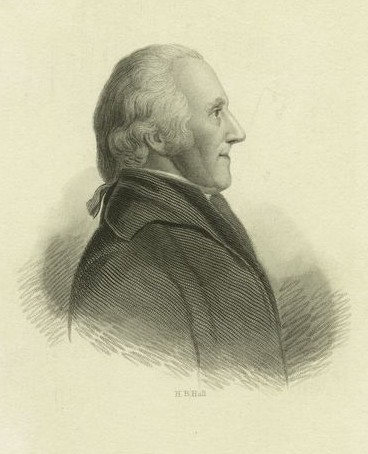

The Sullivan Expedition was a United States military campaign in 1779, led by Major General John Sullivan and Brigadier General James Clinton, where George Washington ordered the Continental Army to respond with force after a series of British and Iroquois forces allied to attack a number of American territories in 1778, including Wyoming, in the Battle of Wyoming, German Flatts, and Cherry Valley.

A. Tenny

Wikipedia;ACD May 2024

Henry Hall (1808-1894)

Wikipedia;ACD May 2024

Wikipedia; ACD May 2024

It has been regarded as a “scorched-earth campaign” where the Iroquois Confederacy resided. A scorched earth campaign is a military tactic where the offensive side destroys everything that would enable the defending side to retaliate or recuperate their losses. In the summer of 1799, General Sullivan, accompanied by a troop of 2500 men, marched north through the Susquehanna Valley into New York and razed over 40 Iroquois villages in the area (Explore PA History). The Sullivan Campaign forces were said to have demolished the villages entirely, destroying crops, food storage, and livestock, and essentially making the land uninhabitable for the indigenous tribes.

Wikipedia; ACD May 2024

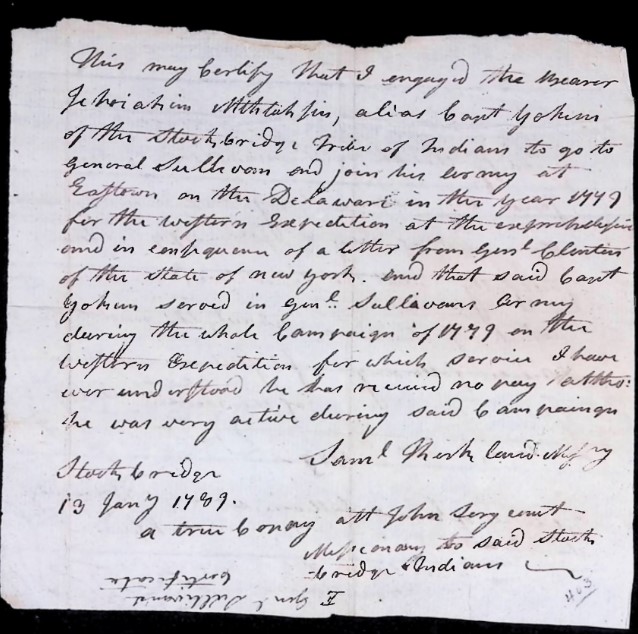

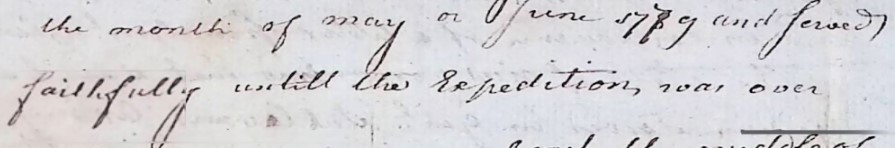

Within our holdings, there is a manuscript that denotes the financial gain acquired from the expedition. 12.70 item 24, reveals a testimony being written by Samuel Kirkland for a Jehoiakim Mtohksin, a Mohican who served in the expedition under Captain Sullivan but was never recompensed for his service. On the reverse of the manuscript, we have an acceptance and response by general Sullivan, indicating that he remembers Mtohksin’s service.

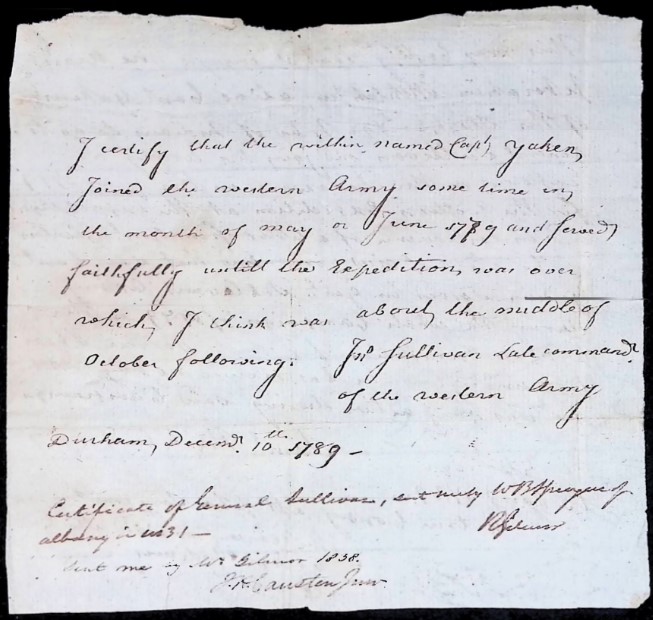

12.70 Item 24: A Testimony by Samuel Kirkland of Jehoiakim Mtohksin, 1789 January 13; Reverse, A Testimony by Jonathan Sullivan in Response to Samuel Kirkland’s Request, 1789 December 10.

The letter depicts a copy by Samuel Kirkland, an educated lawyer and ordained minister, who was later commissioned an missionary to nearby indigenous tribes by the board of correspondence of the Missionary society in 1766. Kirkland is writing a testimony to his knowledge that Jehoiakim Mtohksin, also known by the moniker of Captain Yokhen, served under Captain Jonahan Sullivan during the Sullivan Expedition but was never paid for his service. Kirkland notes that Mtohksin served for the whole campaign and requests attention to John Sergeant, the missionary of the stockbridge tribes, to respond to this neglect.

The reverse of the manuscript was signed by John Sullivan on December 10, 1789. In his testimony, Sullivan certifies that Mtohksin did indeed serve under his command, proposing that he joined in May or June of 1779 and served to the conclusion of the campaign in the middle of October. The bottom of this note states that the certificate of Sullivan was received by R. Seluner by W B Sprague in 1831. Beneath this note, dated 1838, J.H. Causten states receiving the note by Mr. Gilpin.

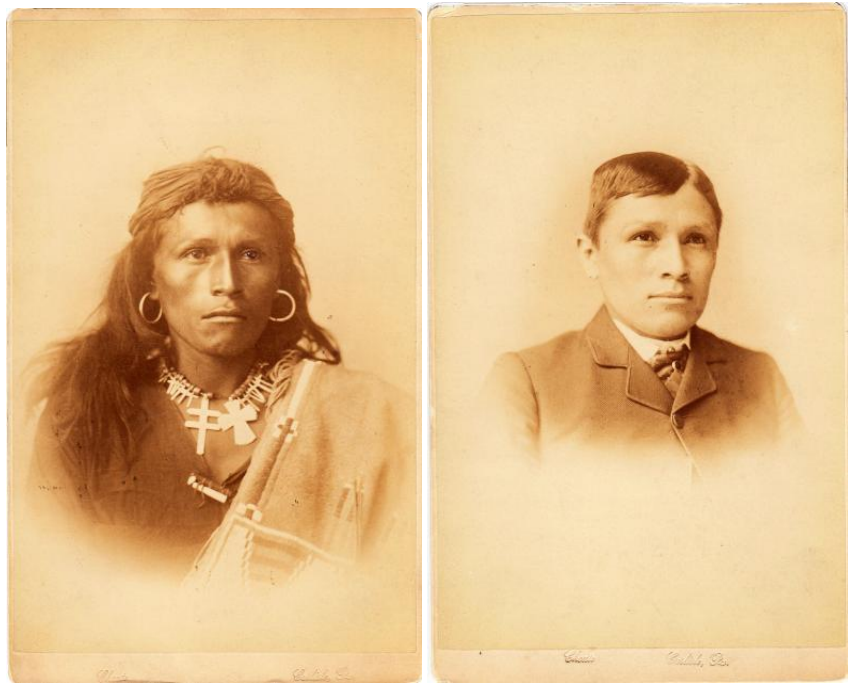

The letter is an intriguing piece that allows us to see into a complex period of the valley’s history. The man in question who served in the campaign against the Iroquois Confederacy is an indigenous man. Jehoiakim Mtohksin was of the Mohican Stockbridge peoples, an early tribe that resided in the eastern edge of the country.

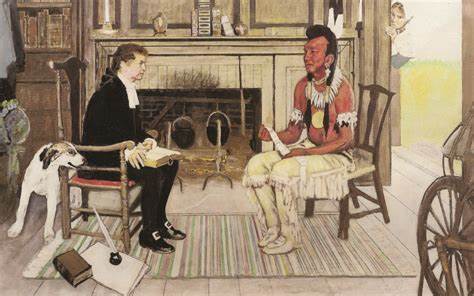

Mohican; ACD May 2024

Their culture was largely matriarchal, with women being in charge of the home and workings of the community while the men were charged with the hunt, traveling greater distances from the lands to forage for “harvests, meat, vegetables and berries” that would later be dried and protecting the community (Mohican). However, as we see in the manuscript, things shift in the region as seminaries, such as John Sergeant and Samuel Kirkland, move into the area with a mission to “convert people from their traditional spiritual practices to Christianity” (Mohican).

Norman Rockwell

Leben, A Journal of Reformation Life; ACD 2024

This began as, seemingly, building an equal partnership between the seminaries and the Mohican peoples. In their book, The Mohicans of Stockbridge, Patrick Frazier explains that some of the Mohicans, Jehoiakim included, were baptized in the faith.

By Patrick Frazier

Google Books; ACD May 202

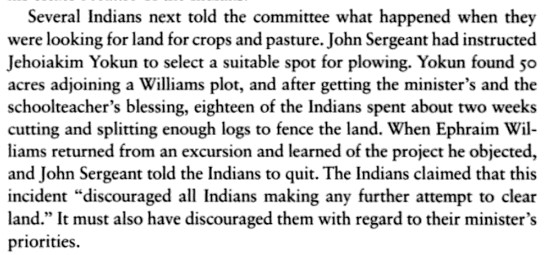

This seems to be from a relationship that the two communities were building. Frazier writes that Jehoiakim was able to buy a great deal of uninhabited land with the minister’s blessings, which allowed them to sow different crops and work the land for the Mohican community. However, the ministers went back on their word when other settlers contested the lands bordering their own, such as Ephriam Williams.

By Patric Frazier

Google Books; ACD May 2024

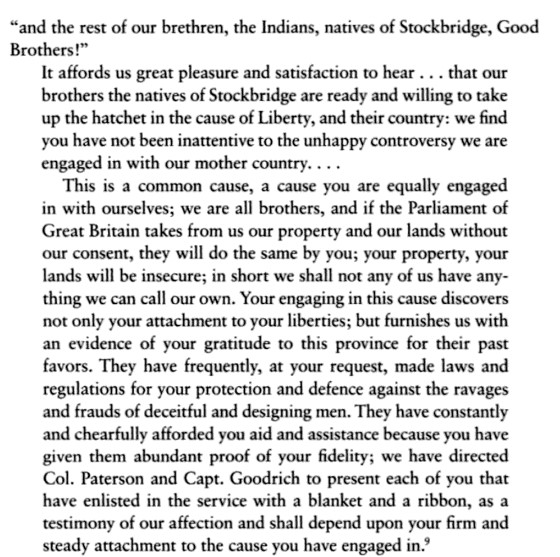

Christian missionaries continued to convert and assimilate the Mohican peoples during this time period, which is plausibly how the Mohicans were swayed into taking part in the Sullivan expedition, as the ministers persuaded Mohicans to take a shared interest in the land.

By Patric Frazier

Google Books; ACD May 2024

This manuscript seems to be a simple plea for a Mohican man to be recompensed for his military service but beneath the surface, it in fact unveils a nefarious history of forced conversion and reconditioning of Native American identity that occurred in the valley and in other parts of the United States. Some early figures in the United States considered Biblical principles to be inherently tied into the framework of the nation’s identity, like Richard H. Pratt, a military figure of the American Revolution and the father of the first ever Native American Boarding school, Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

Wikipedia; ACD May 2024

Pratt proposed that, “Not until there shall be in every locality throughout the nation a supremacy of the Bible principle of the brotherhood of man and the fatherhood of God, and full obedience to the doctrine of our Declaration that “we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created free and equal, with certain inalienable rights,” and of the clause in our Constitution which forbids that there shall be “any abridgment of the rights of citizens on account of race, color, or previous condition.” I leave off the last two words “of servitude,” because I want to be entirely and consistently American (History Matters).

The idea of what an American looked like became largely guided by the principals of a white, eurocentric identity that demanded “students drop their Indian names, forbade the speaking of native languages, and cut off their long hair” (History Matters). The Carlisle school was a flagship Indian boarding school, established in 1879 and run through 1918. It became the model for every other institution to follow, beginning in a military barrack before being taken over by the Department of Interior from the War Department.

Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center; ACD May 2024

These schools abided by a singular and nefarious doctrine, written by Pratt, which proposed to “Kill the Indian, and Save the Man.” His paper proposed that indigenous communities could be regarded as “fully… capable in all respects as we [European/American settlers] are” if only they received “the opportunities and privileges which we possess to enable him to assert his humanity and manhood” (History Matters).

“Beginning in 1887, the federal government attempted to “Americanize” Native Americans, largely through the education of Native youth. By 1900 thousands of Native Americans were studying at almost 150 boarding schools around the United States. The U.S. Training and Industrial School founded in 1879 at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, was the model for most of these schools. Boarding schools like Carlisle provided vocational and manual training and sought to systematically strip away tribal culture” (History Matters).

The structures not only broke apart the community and family structure for many indigenous families, stripping children from the home, and later their culture from them, but made it impossible to reconnect with their family members as language had been robbed from them. Their physical identities were also dramatically reconfigured, forcing them to leave spiritual and cultural practices behind.

National Archives and Records Administration,

National Park Service; ACD May 2024

Similar to the loss of identity by language, culture, and appearance, the language within the manuscript is utilized to sway the indigenous powers to the side of the settlers, though they continue to gain new land by warfare and staging indigenous communities against one another. In the Frazier quote above, we can see how the Iroquois Confederacy would have been swayed to follow the loyalists into the valley alongside Butler’s men, for they have painted the issues at hand as one in the same for the Mohican and Settler alike.

It is an interesting middle ground between the peace negotiations between Native Americans and white settlers that span this time period and the brutal conflicts occurring from the late eighteenth century well into the twentieth century. From the manuscript, we can see that Jehoiakim, a native man, is being monetarily provided for in his hand in removing other indigenous communities from the land. It demonstrates how colonialism is profiting from the destabilization of community and securing more land in the process. More than this, it shows us how his very identity is being reconditioned to align with the interests of the white settlers, as Frazier highlighted, as Sullivan himself notes that Jehoiakim “served faithfully untill (sic) the Expedition was over.”

However, following the brutality of the Sullivan expedition, there were numerous attempts to resolve the conflicts in another manner.

The collection truly demonstrates how peace is a developing history that can be seen in other manuscripts within the collection, such as item 12.71, item 25, a note by Timothy Pickering to Matthias Hollack, 1789 December 15.

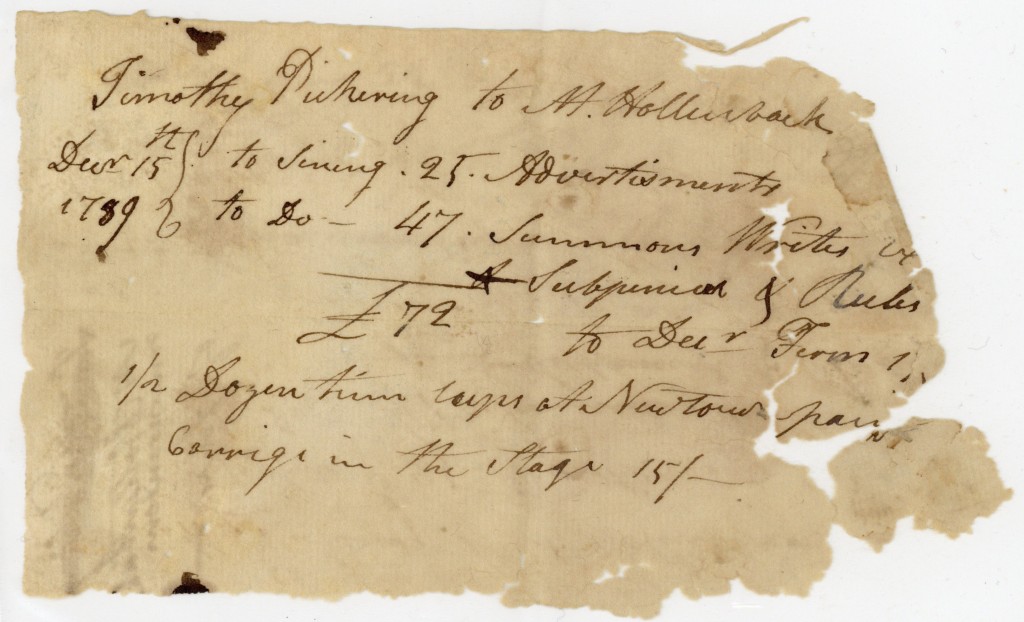

12.71. Item 25: Note by Timothy Pickering to Matthias Hollenback, 1789 December 15.

Timothy Pickering to M. Hollenback

Decr. 15th } to Siving . 25. Advertisements

1789 } to Do- 47. Summons Writes up

& Subpenied & Rules

£72 to Decr[December] Term 17[illegible]

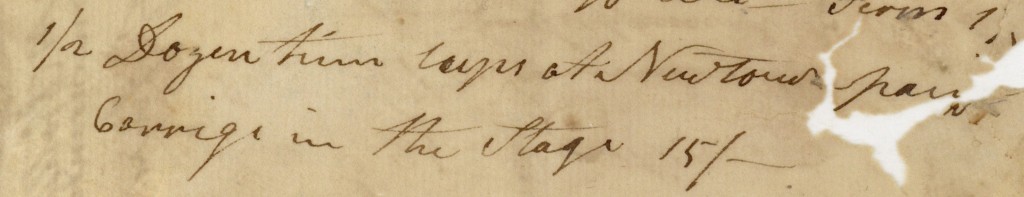

½ Dozen trim cigars at Newtown point [Tioga Point]

Carriage(sic) in the Stage 15/

{back}

Timothy Pickering

M. Hollenback

memorandum

of fares

In the manuscript, Timothy Pickering, another prominent businessman and political presence of the valley, is writing a memorandum of fares to Matthias Hollenback for items received at Newtown and Point, likely Tioga Point.

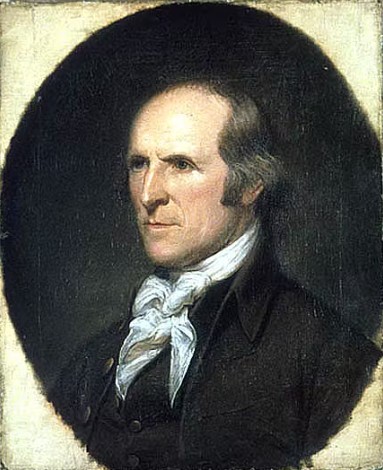

Timothy Pickering was a prominent figure in the valley, being asked by George Washington himself to establish peace ties between Pennsylvania and Connecticut in the land claim conflicts, the Yankee Pennamite Wars, and the settler and indigenous tensions in the valley. Wilkes University Archives has an in-depth blog that traces the history of these conflicts titled A Conflict Forgotten, A History Unexplored. It can be found here.

George Washington’s Mount Vernon;

Accessed May 2024

Pickering held the Secretary of State title under Washington and Adams’ presidencies, and was a Massachusetts representative for both the House of Representatives and the Senate as a member of the Federalist Party. He faced a great political backlash later in his career due to his stances on the War of 1812, whereupon he became a leader of the New England secession movement and was a prominent organizer of the Hartford Convention. The fallout of the convention is largely considered the final nail in the Federalist party and the end of Pickering’s political career.

However, Hollenback and Pickering were close friends and business partners in the early days of the valley, and Pickering’s attention on the brokerage of peace between the settlers and the indigenous tribes can be seen in items such as this note. The note is torn, making the date illegible, but Pickering is writing concerning the response to the Battle of Newton in 1779. This was the only major battle of a larger operation, The Sullivan Campaign, in which the Washington administration ordered the quelling of the Iroquois nation for their support of the loyalists during the revolutionary war.

Wikipedia; ACD May 2024

During this time period there were many battles between Native Americans and the white settlers, and this note addresses the reconciliation attempts that the Washington administration took, whereupon a series of treaties were signed the years following to settle land disputes. Hundreds of people would gather at conferences that would be held to draw up these treaties and sign them. These conferences would take days and would cause tension between the Native Americans and the white settlers. Thus, it helped to have these individual alliances, such as Hollenback, alongside government officials, like Pickering, to establish tones of trust.

By Louise Welles Murray

Google Books; ACD May 2024

Meanwhile, the rural nature of the valley made the citizens entirely reliant upon the river, which was getting shallower and less able to transport the goods required by those below the last point held by the Six Nations: Painted Post. The gathering was a huge historical event for New York. Iroquois confederacy tribes represented included Cayugas, Oneidas, Onondagas, Tuscaroras, Stockbridge, Mohawks and Mohicans. Col. Pickering made an agreement with store owner, Matthias Hollenback, to have special goods on hand for the thousands of visitors to Newtown.

½ Dozen trim cigars at Newtown point [Tioga Point]

Carriage(sic) in the Stage 15/

President George Washington sent Colonel Timothy Pickering to the region to negotiate five pivotal treaties; The Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1784), Treaty of Buffalo Creek (1788, Treaty of Canandaigua (1789), Treat of Tioga Point (1790, and notably in connection to our manuscript, the Treaty of Painted Post (1791). These treaties were aimed at the redesign of boundary lines and relocation of indigenous people.

The Treaty of Painted Post (1791) stated that indigenous communities would accept that land they once held was now property of the United States following the revolutionary war. In exchange for their acceptance of this notion, they would receive the beneficiaries of an alliance with the colonies. They would continue their trade negotiations with the ample stores under Hollenback and other states, while agreeing to move west to new, “unoccupied” lands.

However, it was not merely tensions between these two groups that were unfolding within the valley. As the Continental Congress decided on a decades-long debate over the rights to Pennsylvania’s soil, the question of title and right came into play.

The Rise of Political Tensions and Prominent Names in the Valley

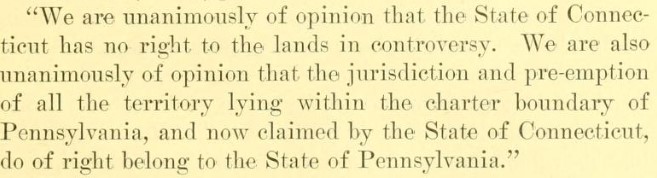

As mentioned, Pennsylvania and Connecticut were in a brutal, three part war called the Yankee Pennamite Wars, the last of which coincided with the Decree of Trenton’s decision to declare that the rights of soil went to Pennsylvania.

Internet Archive; ACD May 2024

“We are unanimously of opinion that the State of Connecticut has no right to the lands in controversy. We are also unanimously of opinion that the jurisdiction and preemption of all the territory lying within the charter boundary of Pennsylvania, and now claimed by the State of Connecticut, do of right belong to the State of Pennsylvania.”

In reaction to this decree, Pennsylvania disregarded the current rights to land title for any Connecticut settler in the area. The Pennsylvania Assembly had the Connecticut settlers removed from the valley forcibly, sending families of mostly women and children into the woods which would institute numerous resolutions that would ultimately restore Connecticut settlers to the valley land they initially claimed. Two of these such acts were the 1788 bill, “A further act for quieting the disturbances at Wyoming, and for confirming to certain persons called Connecticut claimants, the lands by them claimed with the county of Luzerne,” and the 1799 Act of Assembly, “An Act for offering compensation to the Susquehanna claimants of certain Lands within the seventeen Townships in the County of Luzerne and for other purposes therein mentioned.” We have our own versions in the McClintock collection within Subseries II: Susquehanna Claim, 1770-1801 here and here. A blog post that goes into depth in regards to these resolutions and acts can be found here.

The first act in 1788 helped to establish legal parameters that would enable Connecticut claimants to bring forth their land claims. The document created a recognition of 17 townships in which the lands previously held by Connecticut claimants could be recovered, some of those being named in Salem, Newport, Hanover, Wilkes Barre, Pittstown, Kingston, and Plymouth, even if held by Pennsylvania claimants at the time of request. It gave them legal protection and support in recovering their lands that was recognized by the State of Pennsylvania, while also plainly voiding all present Pennsylvanian claims. Yet, Pennsylvania included language that still attempted to protect Pennsylvanian residents claims, explicitly restricting the lands to the townships in question and resituating the county borders to expand the government’s reach.

While some of the claimants believed this would enable them to have a closer hand and influence over local government affairs, others felt that it brought the hand of government too close to their front door. Many of the more extreme Connecticut factionalists, such as the “front man of the Wild Yankees,” John Franklin, argued that they required a healthy separation from the government in being able to maintain their arguments of power (Moyer).

The 1788 act not only served to divide the Connecticut and Pennsylvania settlers in language and land, but further created a divide between Connecticut peoples, as the act only recognized the lands held by Connecticut claimants before the Decree of Trenton,

We see the people of the valley begin to turn on Pickering. With his avid favor for the state authority over the rights of title and jurisdiction, Pickering becomes isolated from those in the valley as he is largely seen as an arm of the governing bodies until he is ultimately kidnapped on June 26th 1788 by a group labeled the “Wild Yankees.”

The Lackawanna Historical Society has a collection called the John Jenkins Papers, which students of Wilkes University are currently aiding in processing and transcribing. This collection contains numerous manuscripts that depict the events occurring in the Valley, from the American Revolution, the Pennsylvania Connecticut conflict, and beyond. These personal accounts allow us to see how these animosities between the Connecticut settlers and Pickering were unfolding.

John Jenkins Papers, Lackawanna Historical Society.

[Note: Collection is currently still be processed so finding aid is unavailable]

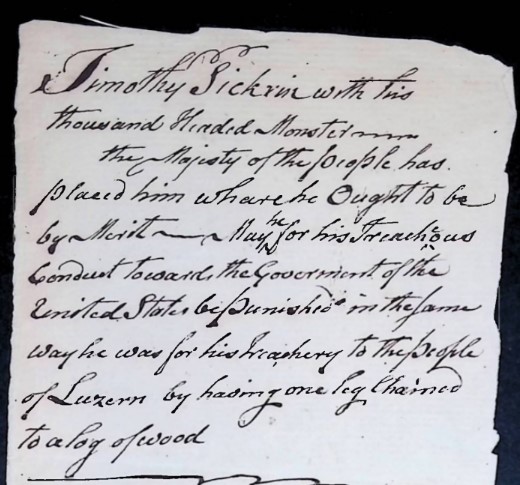

Transcription: “Timothy Pickrin [Pickering] with this thousand Headed Monster ~~~

the Majesty of the people has

placed him whare (sic) he Ought to be by Merit— May ^he for his Treach^erous [Treacherous] Conduct toward the Government of the United States be Punished in the same way he was for his Treachery to the People of Luzerne by having one leg Chained to a log of wood”

In the manuscript above, John Jenkins, a lieutenant colonel in the American Revolutionary War and a Connecticut claimant, writes a number of toast lines following what is assumed to be the kidnapping of Pickering. Pickering was kidnapped for a few short months from March to June, after the 1788 act was passed. This highlights how quickly the tensions devolved, seen clearly here as Jenkins makes Pickering a sport of public ridicule, naming him a “thousand headed monster” while elevating the power of the people who have now “placed him where he ought to be.”

It is indicative of an interesting shift in the rule of law that we see playing out in the valley through manuscripts such as the one above and our own collections. Where does the right view lie? In the acts proposing compromise and peace, we see a clear manipulation of legal powers that enable Pennsylvania to remain in a seat of power. The government places Pickering in a position to attempt peace while allowing them to remain abreast of what the parties who question them, and as a result, we see the people attempt to take power into their own hands with acts of violence.

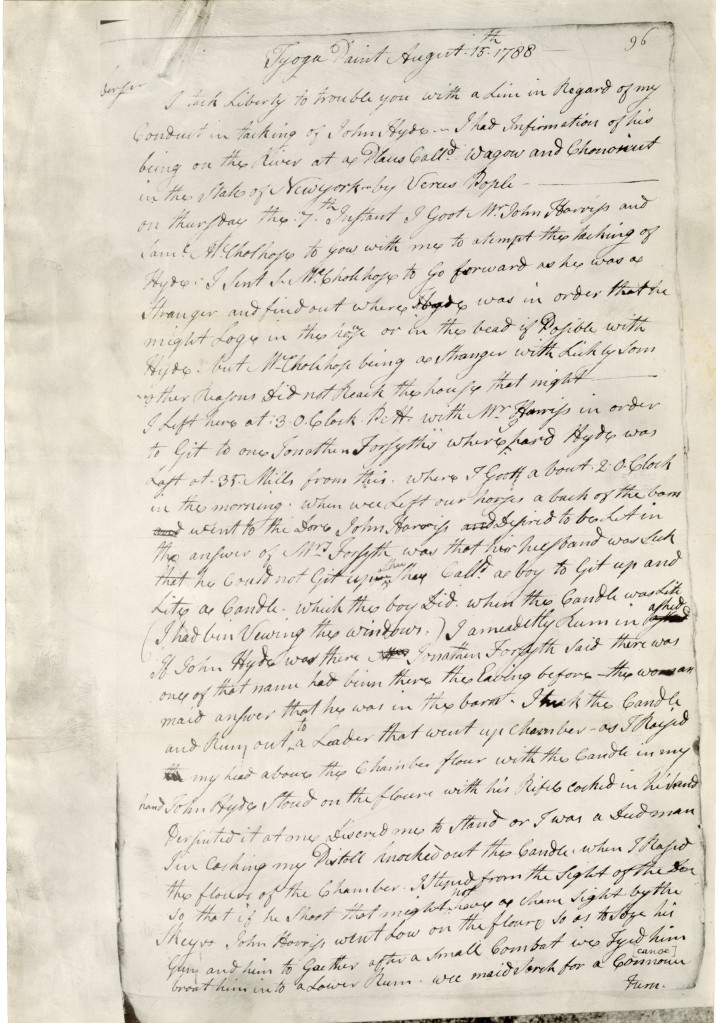

In our collection, we have a manuscript written by Hollenback to Pickering, 12.69 item 23, where he explains his capture of John Hyde, a man responsible for Pickering’s kidnap. It allows us an interesting perspective of how the local government responded.

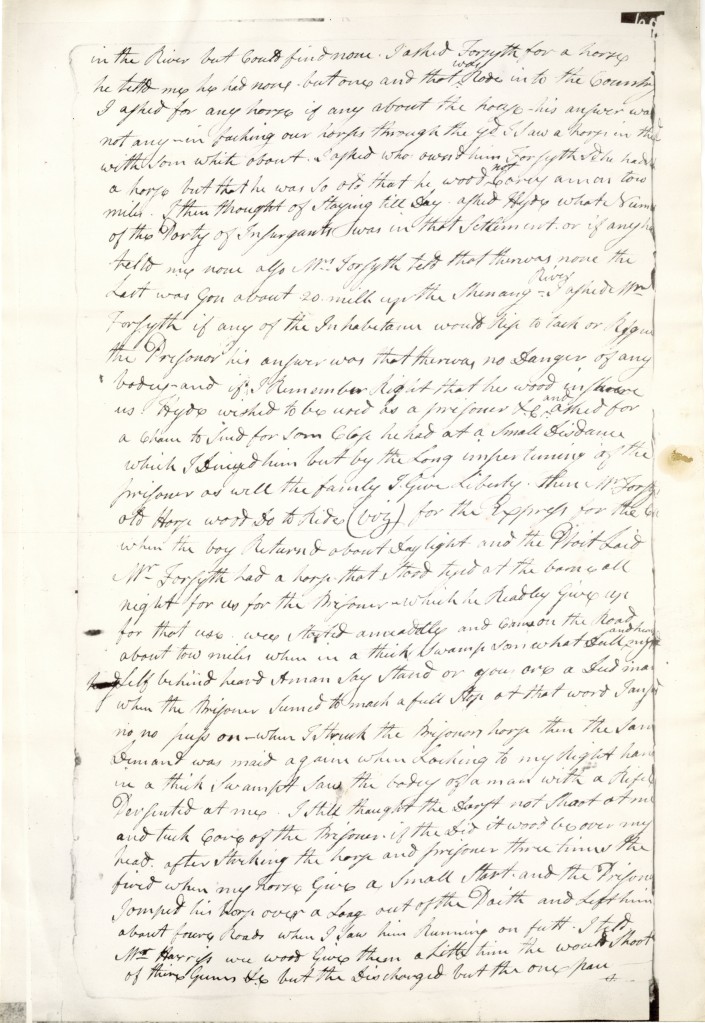

12.69 Item 23: Letter from Matthias Hollenback to Timothy Pickering, 1788 August 15.

96

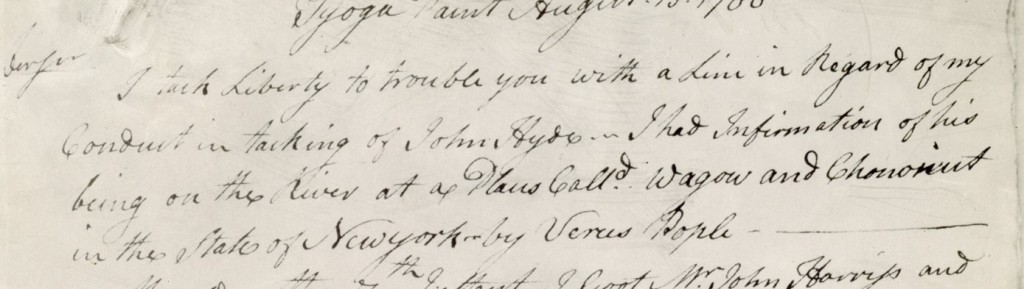

Tyoga Paint (sic) August 15th 1788

De[a]r Sir

I take Liberty to trouble you with a Line in Regard of my Conduct in taking of John Hyde. ~~ I had infirmation [sic] of his being on the River at a Placs (sic) Call[e].d Wagow and Chononicut [Connetquot?] in the State of New York by Verus Pople (sic) [People].

On thursday the 7th Instant I goot [sic] Mr. John Harriss and Samuel McCholhope to gow [sic] with me to attempt the taking of Hyde. I sent Sir McCholhope to go forward as he was a stranger and find out where Hyde was in order that he might loge (sic) in the house or in the bead (sic) if possible with Hyde. but McCholhope being a stranger with luck by som (sic) other Reasons did not Reach the house that night.—

I left here at 3. O.Clock P.M with Mr.Harris in order to git(sic) to one Johnathan Forsyth where I hard(sic) Hyde was last at 35 miles from this I goott(sic) about 2 O.Clock in the morning. When wee (sic) left our horses a back of the barn

If John Hyde was there

turn

Page 2:

in the River but Could find none. I asked Forsyth for a horse he told me he had none— but one that ^ was Rode in to the country. I asked for any horse if any about the house – his answer was not any~~ in backing our horses through the yd. I saw a horse in the [yar]d with som (sic) white about . I asked who ownd (sic) him Forysth s.d [said] he had a horse but that he was so old that he wood (sic) ^ not carry a man tow (sic) [two] miles. I then thought Staying till Day asked Hyde what Num[ber] of the Party of insurgents was in that Settlement or if any he telld (sic) me none also Mr. Forsyth teld(sic) that there was none. the Last was gon (sic) about 20 miles up the Shenang (sic) [Shenango] ^ River asked Mr.Forsyth if any of the Inhabitants would rise to take or Re[lease] the Presonor (sic) his answer was that there was no Danger of any body— and if I Remember Right that he wood (sic) inshore (sic) [insure] us. Hyde wished to be used as a presonor (sic) &c [etcetera] ^and asked for a chance to send for som(sic) close(sic) [Clothes] he had at a small Disdance which I Deniyed(sic) him but by the Long impertunning(?) of the prisoner as well the family I Give Liberty then Mr. Forsyths old Horse wood (sic) Do to Ride (viz) for the Express for the C[illegible] when the boy Returned about Daylight and the Ploit (?) Said Mr. Forsyth has a horse that Stood tyed (sic) at the barn all night for us for the Prisoner ~ which he Readley (sic) Give (sic) up for that use. wee (sic) Started ameadlly (sic) [immediately] and came on the Road about tow (sic) [two] miles when in a thick swamp some (sic) what tall(?) ^ and head(?) my

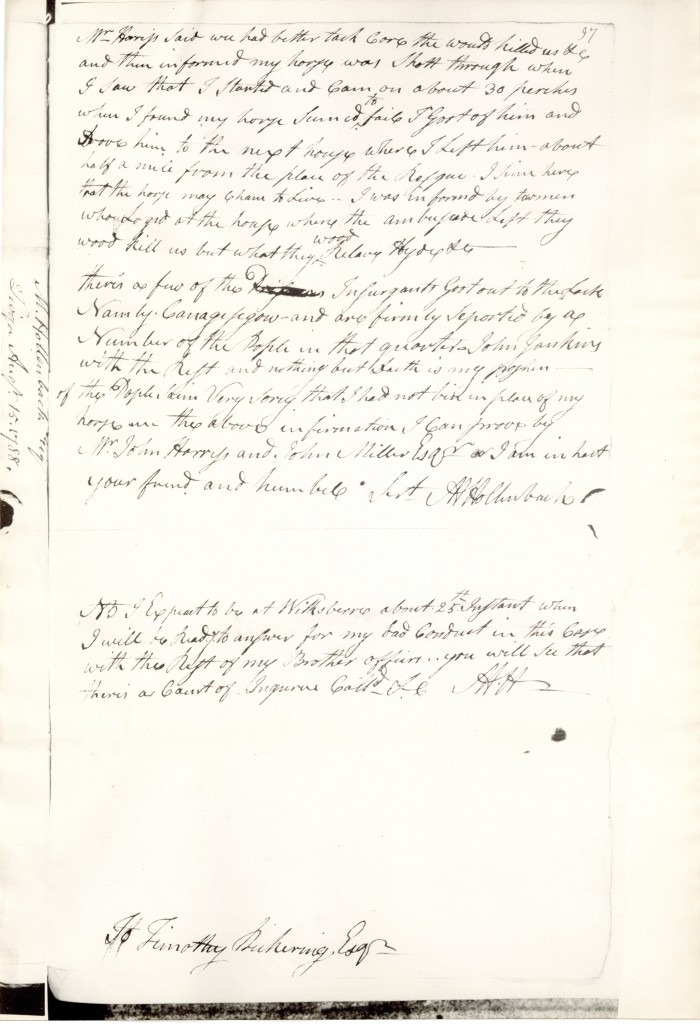

Page 3:

Mr. Harris said wee (sic) had better tack (sic) care the would killed us &c[etcetera] and then informed my horse was shott (sic) through where I saw that I started and came (sic) on about 30 perches when I found my horse Sunned(sic) [soon?] ^to fail I Goot (sic) of[f] him and Drove him to the next house where I Left him–about half a mile from the place of Resque (sic). I Since here (sic) that the horse may chance to Live —- I was informed by townsmen who Loged (sic) at the horse where the ambushed Left they wood (sic) kill us but what they ^wood Release Hyde &c[etcetera] &c ———

there’s (sic) [There is] a few

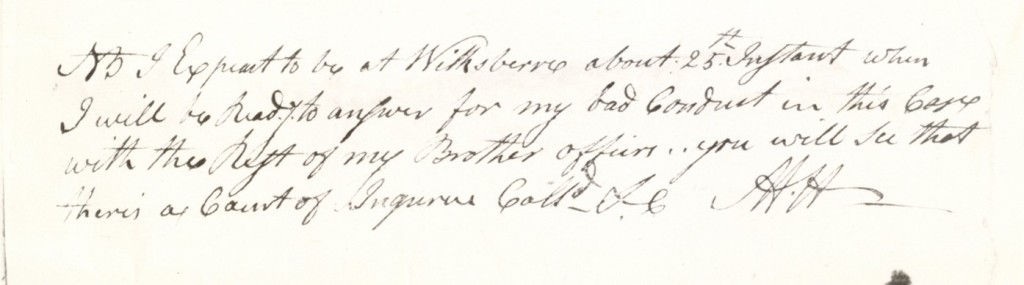

NB[nota bene] I Expect to be at Wilkesbarre about 25th Instant when I will be Ready to answer for my bad Conduct in this case with the Rest of my Brother officers. you will See that there’s (sic) [there is] a Court of Ingueus(?) Call[e]d

MH [Matthias Hollenback]

Hollenback explains in detail how he fought off fire from Hyde, successfully capturing him by commandeering a horse and chasing him up river after Hyde fled a house he had been hiding in. What is interesting about this manuscript, aside from the daring excursion and rendering of justice, is how Hollenback is self-aware of the crimes and mishandling of his own actions.

He begins the letter by stating that the intention of it is to “take Liberty to trouble you with a Line in Regard of my Conduct in taking of John Hyde.”

De[a]r Sir

I take Liberty to trouble you with a Line in Regard of my Conduct in taking of John Hyde. ~~ I had infirmation [sic] of his being on the River at a Placs (sic) Call[e].d Wagow and Chononicut [Connetquot] in the State of New York by Verus Pople (sic) [People].

It is a moment that addresses the need and attention for law and order within the counties, even when apprehending a criminal. It recognizes the importance of moral character within the valley as it grows and develops within the country.

Hollenback even mentions it in the conclusion of his letter, accepting accountability in the actions he took and stating the place and time he will arrive to hear judgment.

NB[nota bene] I Expect to be at Wilkesbarre about 25th Instant when I will be Ready to answer for my bad Conduct in this case with the Rest of my Brother officers. you will See that there’s (sic) [there is] a Court of Ingeus Call[e]d

MH [Matthias Hollenback]

This manuscript highlights the core intention behind some of the earliest documents in the collection, while going beyond mere land ownership by focusing on the implementation of law and reason within the territory. Hollenback’s acknowledgement of his wrongs signifies a broader objective to the establishment of law and order within the Wyoming Valley. Influential people, just like ordinary citizens, were held to the same expectation.

The Lackawanna Historical Society’s Jenkins Papers also has a manuscript that demonstrates the seriousness with which the government responded to the incident.

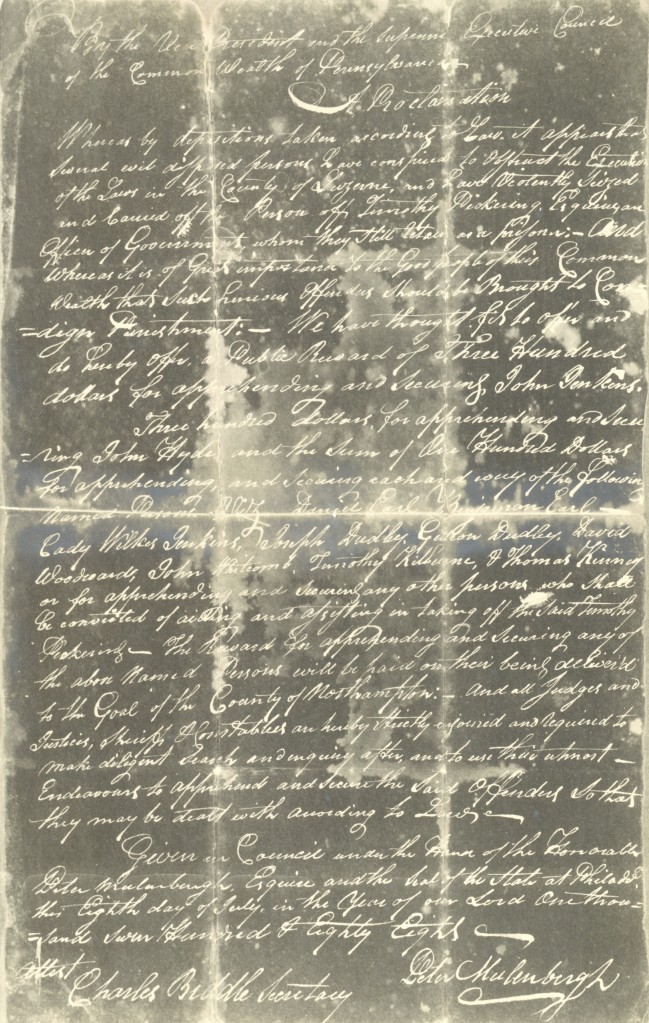

A Photostat of a July 8, 1788 Proclamation by Peter Mulenburgh, Offering Rewards for Arrest of Col[onel]. John Jenkins, John Hyde, and others, [no date].

John Jenkins Papers, Lackawanna Historical Society.

[Note: Collection is currently still be processed so finding aid is unavailable]

By the Vice President and the Supreme Executive Council of the Common Wealth of Pennsylvania

Whereas by depositions taken according to Law it appears that Several evil disposed persons have conspired to obstruct the Execution of the Laws in the County of Luzerne and have Violently Seized and Carried off the Person off (sic) Timothy Pickering Esquire and Officer of Government, whom they still Retain as a prisoner:– And whereas it is of Great importance to the Good people of this Common Wealth that such henious (sic) Offenders should be Brought to Condign Punishment:— We have thought fit to offer and do hereby offer, a Public Reward of Three Hundred Dollars for apprehending and securing John Jenkins.

Three Hundred dollars for apprehending and Securing John Hyde and the sum of One Hundred Dollars for apprehending and Securing each and every one of the following named Persons Viz: Daniel Earl Benjamin Earl– Cady Wilkes Jenkins Joseph Dudley, Gideon Dudley, David Woodward, John Whitcomb, Timothy Kilburne, & Thomas Kinney or for apprehending and securing any other persons who shall be convicted of aiding and assisting in the taking off the said Timothy Pickering~~ The Reward for apprehending and securing any of the above named Persons will be paid on their being delivered to the Goal of the County of Northampton:— And all Judges and Justices, Sheriffs & Constables are hereby Strictly enjoined and required to make diligent Search and enquiry after, and to use their utmost – Endeavours to apprehend and secure the said Offenders So that they may be dealt with according to Law—

Given in Council and under the House of the Honorable Peter Mulenburgh, Esquire and the seal of the State at Philad[elphi]a this Eight day of July, in the Year of our Lord one thousand seven Hundred & Eighty Eight—

Attest Peter Mulenburgh

Charles Biddle Secretary

This LHS manuscript provides us with the state government’s perspective on the Timothy Pickering kidnapping compared to the local Mattias Hollenback one that we have in our collection. Their approach and language is more extreme in villainizing the men by describing the kidnappers as, “Several evil disposed persons,” and offering various monetary rewards for their capture. The purpose of this state committee’s proclamation seems more aimed at retribution for Pickering’s kidnapping compared to Hollenback’s account which asserts personal accountability for how the law-breakers are retrieved, even amid a public reward. Each manuscript holds a different tone and perspective of the kidnapping, ranging from the view of the people, the local government, and finally the state response, allowing us to see how the rule of law was being assessed and refined on a multilayered front.

As we can piece together this kidnapping from multiple sources, we can see that these manuscripts offer a comprehensive insight into the development of law and justice in the valley. Hollenback’s and Biddle’s letters underscore the structures of order and stability that local governments were establishing after extended periods of conflict, while Jenkins’ toast examines the pushback of the people. Each manuscript highlights how the events of history can never be truly understood through one perspective, and offers us a deeper understanding of how this region’s conflicts were addressed and resolved in the late eighteenth century.

Meanwhile, as tensions in the valley were building upon one another and being remedied, a new threat loomed overseas. The French Revolution had a greater impact on the region than a modern day resident may think, as it saw the creation of a whole new community: the French Asylum.

Creating Refuge in the Valley: The French Azilum

Explore the French Azilum

The French Azilum; ACD May 2024

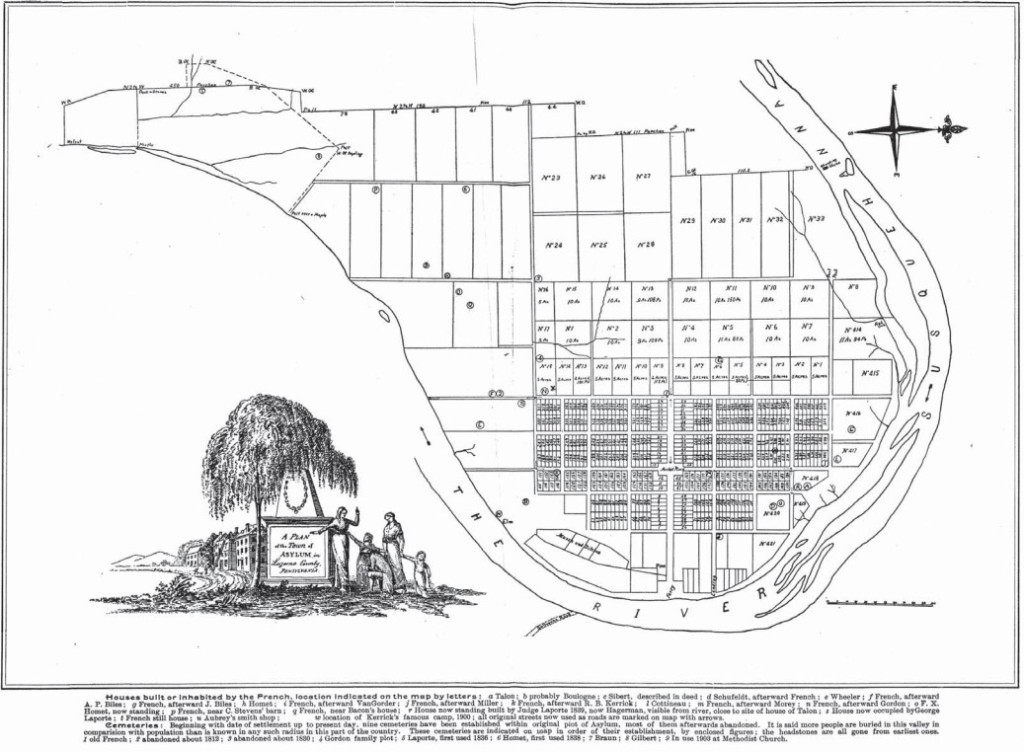

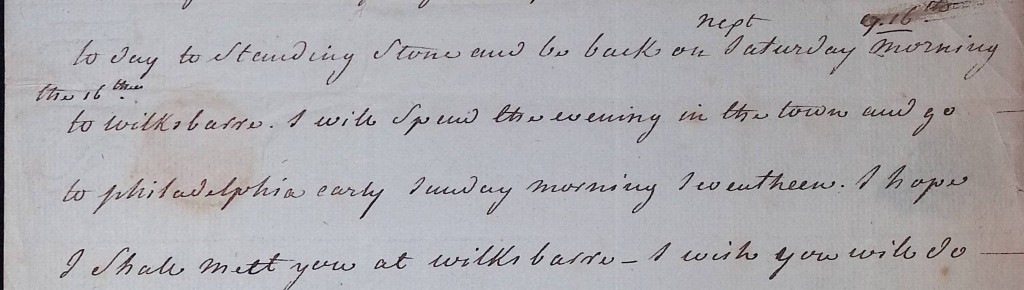

The French Azilum was an asylum settlement that consisted of French royalists, established in Bradford County during the fall of 1793 and the spring of 1794, when Pennsylvania residents sought a way to bolster the economy while aiding French refugees.The purpose of the settlement was to house and support those fleeing the French Revolution primarily, as well as the enslaved rebellions occurring within the French colony of Saint-Domingue, Haiti.

Explore the French Azilum

The French Azilum; ACD May 2024

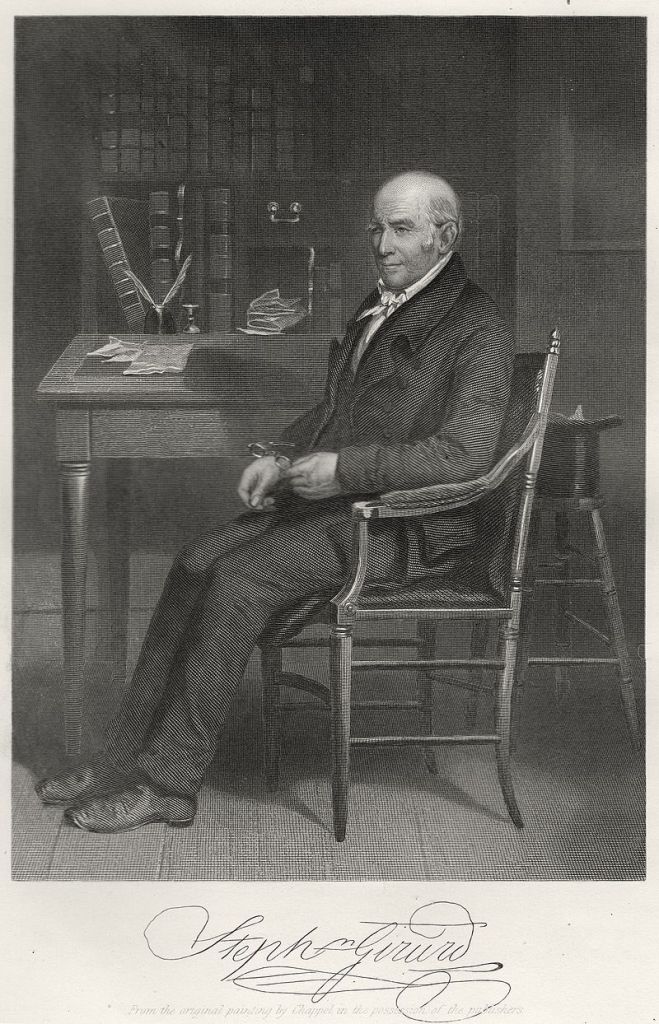

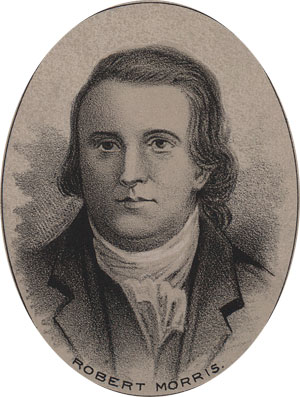

There were many influential men of Pennsylvania and the valley, such as Stephen Girard and Robert Morris, who felt sympathy for those fleeing France due to their earlier connections and support during the American Revolutionary War.

Wikipedia; ACD May 2024

Girard would become a pivotal voice in metropolitan areas, as he founded the French Benevolent Society of Philadelphia, and spoke about the plight that any of the French refugees were experiencing. His speeches were geared at swaying the general public’s opinion, encouraging them to aid financially and support a project to provide the essentials so desperately needed (Internet Archive).

While gathering support from the public, Morris and his business partner, John Nicholson, would find the financial means to purchase the lots needed for the venture. They would become the financial backbone of these earliest stages of establishing the French refugee community.

by Norman B. Wilkinson

Internet Archive; ACD May 2024

Transcription:

“An American who was close to several of the principal French exiles responsible for tlie founding of the colony was Pennsylvania’s Senator Robert Morris, financier of the Revolution, merchant, and land speculator. Through him and his partner John Nicholson, Pennsylvania’s comptroller general, a large tract of land in the northern wilderness of the State was to be purchased and transformed into a woodland Arcadia.”

by Ole Erekson, c. 1876,

Wikipedia; ACD May 2024

They proposed the settlement to house and support those fleeing the revolution. Though their efforts were positioned as an act of support and compassion due to the high French population in Philadelphia and alliance ties persisting for the American Revolution, there were also many who viewed the settlement as a lucrative investment for the country (French Azilum).

Their endeavors would be financially supported by Matthias Hollenback, who purchased a number of additional lots that had been under the Connecticut titles in order to expand the possibilities of Asylum. More than lots alone, Hollenback purchased the resources and goods that many of the refugees in the community needed. He became a middleman between the French Azilum community and a foreign terrain, as he would help them purchase the materials they needed and find a return on the investment at a later time.

Zuke Aloysius Sarsfield

ILL Penn State University; ACD May 2024

Wilkes University Archives has an in depth blog post that examines the financial entreprises occurring in the valley, including an exploration of Hollenback’s connections to the early organization and support of the Azilum community, titled “There’s a Richness to the Valley’s Soil,” which can be found here.

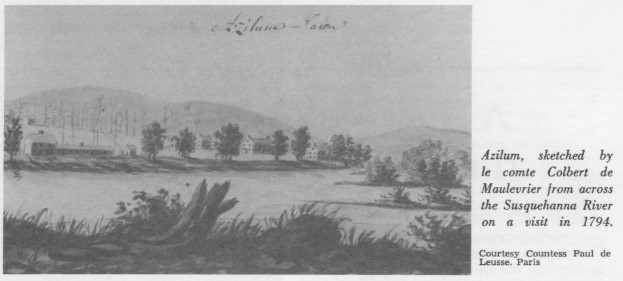

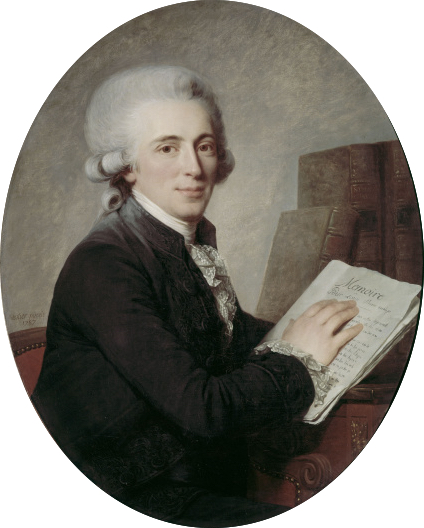

What is compelling about the history from this collection’s advantage is that it contains two letters from the very beginning, 1793, authored by two of the settlement’s French figures. It was not by the means of the men already situated in the valley alone that provided the successful establishment of Azilum. They were aided by two French men, Louis de Noailles and Antoine Omer Talon, who were prominent figures in establishing the community alongside the financial investors and Hollenback.

Louis de Noailles, brother-in-law of American Revolutionary figure, Lafayette, was a French peer and politician who advocated for “reducing traditional privileges of the French aristocracy,” despite being born into the system himself (Internet Archive). He also joined in service during the American Revolution and aided American forces in the Battle of Yorktown.

A French Asylum on the Susquehanna River, page 2

by Norman B. Wilkinson

Internet Archive; ACD May 2024

Wikipedia; ACD May 2024

His political leanings made him a supporter of the initial revolutionary principles. He served as a deputy of the nobility to the States General in 1789, and later as an assembly member, where he proposed to abolish the privileges of the Feudal system and its aristocracy. Though he was an impressive military force, he began to seek opportunities of refuge when he and many other “Republicans…fell under the displeasure of Robespierre ” (The French at Asylum, page 6-7). Noailles lost both his sister, Adrienne de La Fayette, his mother and grandmother were all sent to the guillotine by Robespierre.

Thus, he began to network and meet with United States powers to propose the idea of a settlement in the country for those who Robspiere had confiscated the property of and threatened death. Noailles dined with many businessmen and professionals to secure the investment needed, such as the President of the Bank of the United States.

David Craft

Google Books; ACD May 2024

Noailles succeeded in establishing the French Azilum by strategically parlaying with the intended audiences: sympathetic American parties who had not forgotten the role that French parties had played during the American Revolution. It was his ability to get these meetings and secure sympathy and support for their struggle that laid the foundation for the refuge in Bradford county later.

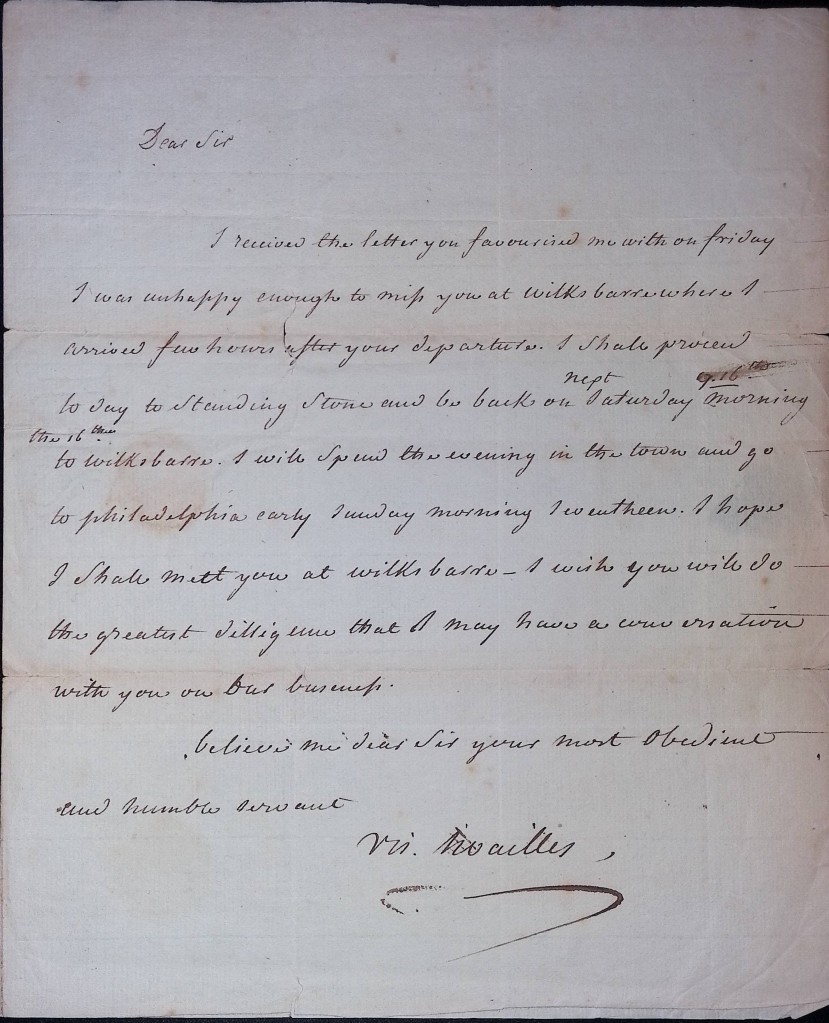

In our collection, we have a letter from Noailles that demonstrates his attention to building these strong professional relationships. 12.76a Item 30a depicts a letter between him and Hollenback, where Noailles has recently missed Hollenback.

12.76a. Item 30a: Letter from Louis Marie De Noailles to Matthias Hollenback, 1793 November 8.

I received the letter you favourished me with on Friday I was unhappy enough to miss you at Wilkes barre where I arrived few hours after your departure. I shall proceed to day to Standing Stone and be back on next Saturday

believe me dear sir your most obedient and humble servant.

Vis. Noailles

{back}

Viscount De Noailles

Letter Novr. 8.th 1793

The Asylum Company

To M. Hollenback

The language is important when reading the manuscript; while it seems fairly plain and straightforward, the timing of the letter impacts the meaning behind them. The French Azilum construction began in the fall of 1793, around the timing of this letter in November of the same year. Noailles makes an intentional move to address having missed Hollenback and make plans to remedy it with a future meeting.

It makes us consider how efficient and resourceful Noailles would have had to be with his time during these early days of planning the Asylum and seeking its investors. He has already secured the financial backing and support within the asylum, but his professional demeanor demonstrates the continued attention he would have had to pay in maintaining these relationships. The stress that he puts in the letter allows us to infer the importance of meeting with Hollenback, a prominent name and figure of industry within the valley, for Noailles gives him explicit, minute details to his whereabouts between missing Hollenback and the next time they shall meet.

He even places the date in the margin, ensuring that there is no room for mistaking his schedule, and reassuring him that they will have an understanding of where and when to meet, for he mistakes the date at first. In the crossed out section, Noailles originally writes 9, presumably thinking that to be the Saturday in question before realizing it to be too early, for the 16th is the following week. These minute details within this manuscript provide deeper insight into the level of coordination and community planning that was necessary to establish the French Azilum. Noailles’ meetings reveal the need for the initial investors of the valley to even bring about the means of its creation.

Eventually, the community is established and buildings are erected. Asylum consists of 1,600 acres, three hundred of which are constructed as a town square that possesses a “two acre market square at its center, from which ran streets laid in a gridiron” (Internet Archive, page 3). With the settlement in place, however, the question then became not how to support the means of Asylum, but the needs of the people within.

by Norman B. Wilkinson

Internet Archive; ACD May 2024

Alongside the endeavors of Noailles, a member of the French magistracy, Antoine Omer Talon, became an avid business liaison and supporter of the communities growth. Omer had worked as an attorney and chief justice of the French criminal court before the French Revolution, and was considered a counter-revolutionist. He was known most prominently for his “fearless and unflinchin defence of the royal prerogative,” which saw him shortly imprisoned before the charges could not be sustained and he was ultimately released (Craft, 8).

by Norman B. Wilkinson

Internet Archive; ACD May 2024

Wikipedia; ACD May 2024

Where Noailles was seeking to establish a community that offered security for those fleeing the violences of the war, Talon sought to lessen the hardship of his countrymen, many of whom were former French aristocracy.

by Norman B. Wilkinson

Internet Archive; ACD May 2024

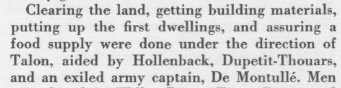

Thus, much of Talon’s work was working with merchants and laborers to lessen the back-breaking work required in the early days of Asylum. The item by Talon in our collection demonstrates this very interest in outsourcing the labor and mitigation business for the community. 12.76 item 30b a letter by Antoine Omer Talon denoting dues owed to Isaac Dewitt, for service rendered to Azilum.

12.76b. Item 30b: Letter from Antoine Omer Talon to Isaac Dewitt, 1794 July 30.

July the 30.th 1794

Mr. Talon to hanging five pare of shutters — Lo:-

August the first – to hanging three pare dito — o: 3

Talon 8

3 . 6. 1

3. 15

3.

18.

Recd [Received] the order Isaac Dewitt 3.7.6

Comte Omar de Talon was the founder of the French settlement at Asylum.

Mr. Talon Order

V Dewitt Recd

8/-

As was noted by Wilkinson, extreme winter weather would set in to the valley quickly, especially for a community that was being constructed in the later part of the year. Having shutters and other safeguards from the weather outside would have been necessary to endure the weather. Moreover, the refugees would most likely have had little on their person when they fled France, leaving them more vulnerable to the conditions. What is intriguing about Talon’s letter is that it gives us the context of distance, being written in the summer of the following year.

It demonstrates that the community is likely growing and developing, plausibly adjusting to needs after facing the harsh winter, but it also shows financial stability as they can afford to continue building upon their homes.

That is what is really intriguing about the manuscripts in this collection, as they offer minute insights into how various regions of the valley were growing and developing as they became more stable. What began as a conversation over dinner grew to over 400 plots and an expanding population. The French Azilum is not the only community that saw rapid growth in the valley, however.

Building Up of Towns and Business Ventures

Not only did these important figures and civic leaders in the Wyoming Valley lay the foundation for our various cities’ laws and governments, but they quite literally built the towns we live in and surveyed the land we walk on.

A place rich with historical history is right across the Market Street Bridge from Wilkes’ Campus, the well loved Kirby Park! I’m sure Wilkes-Barre residents have taken a stroll through this park at least once in their lifetime, and as I delved deeper into the contents of this subseries I came across meeting minutes written by Jess Fell on March 19th 1804 that revealed the parks development which was once the 100- Acre farm of Matthias Hollenback.

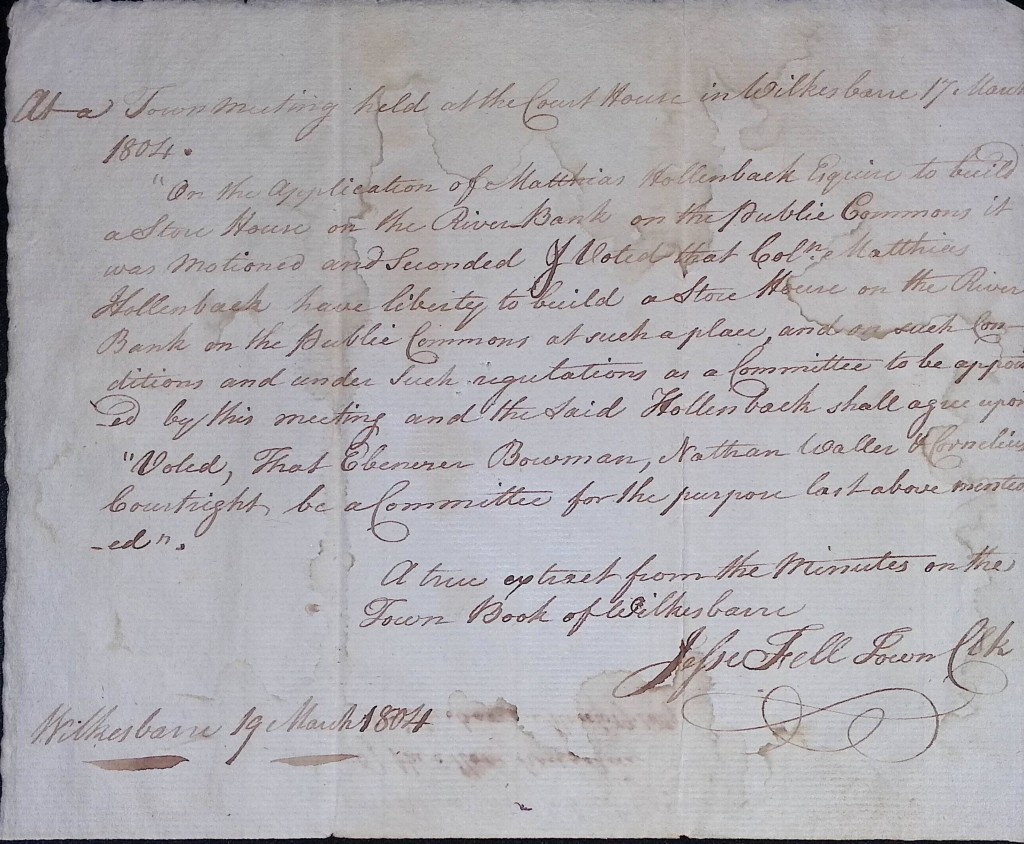

12.79. Item 33: Meeting minutes by Jesse Fell, 1804 March 19

At a Town meeting held at the CourtHouse in Wilkesbarre 17 March 1804.

“On the application of Matthias Hollenback Esquire to build a Store House on the River Bank on the Public Commons it was motioned and seconded & Voted that Colo. Matthias Hollenback have liberty to build a Store House on the River Bank on the Public Commons at such a place, and on such Conditions and under such regulations as a Committee to be appointed by this meeting and the said Hollenback shall agree upon”

“Voted, That Ebenezer Bowman, Nathan Waller, Cornelius Courtright be a Committee for the purpose last above mentioned.”

A true extract from the minutes on Town Book of Wilkes barre

Jesse Fell Town Clk

Wilkes Barre 19 March 1804

In these minutes, Fell records a business proposal presented by Hollenback to build a farm store along the river. This would become the business hub where Hollenback would stock the goods to be transported into the valley so that citizens and neighboring Indigenous tribes could have easier access to purchasing what they would need.

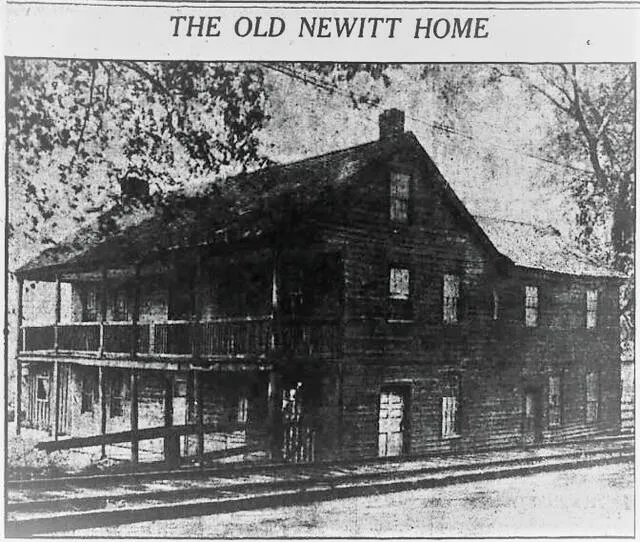

withstood floods for more than 100 years.

Picture published Wilkes-Barre Record April 18, 1912.

Times Leader; ACD May 2024

It is really cool to consider how a property that has been revolutionized into a vibrant outdoor public space during our times, was once a site for another progressive venture in the valley! The store was situated on a larger farm that Hollenback owned, where he would raise “produce of beans, buckwheat, watermelons and corn,” which he would offer for sale to those in the valley or trade in a barter system with those in the valley so they did not have to figure out larger ventures (Times Leader). It is plausible that these goods would have been more affordable for those in the rural valley, as they would be able to access systems of credit or borrowing with rural general stores (Heritage Society).

[circa 1895 and 1910]

Library of Congress; ACD May 2024

“Patrons, who were predominantly farmers, came to the store to buy their staples but they also received trust, understanding and credit when needed. In the early days, business transactions often took the form of trade and barter – furs and hides for cornmeal and coffee. Since farmers did not have ready cash until they sold their crops or livestock, purchases were frequently made on credit and the transactions were recorded by hand in ledger books” (Heritage Society).

It is also interesting to see how these early ventures went about their proposals and approvals. The minutes display what appears to be a secondary meeting to approve the venture.

“it was motioned and seconded & Voted that Matthias Hollenback have liberty to build a Store House on the River Bank on the Public Commons at such a place, and on such Conditions and under such regulations as a Committee to be appointed.”

As many families were not able to access forms of cash easily, general store owners would allow for families in rural areas to trade for what they needed or begin a credit tab that they could settle at a later date.

The structure of the proposal is also intriguing. Rather than the professional one-on-one meetings that many of us may think of when looking for a business license, or even a long line in a government building, it is intriguing to consider Hollenback bringing his proposal before the meeting for a vote on the prospect of adding a new business in the valley. There is almost a recognition of how it enhances the means of the community as well, for they leverage that the building is situated on the Public Commons, plausibly close to those living in the town.

These manuscripts demonstrate how the people of the valley moved beyond the simple infrastructure of the towns and cities, to begin building up the enterprise of the valley. With a strong business market building in the valley, we begin to see interest in people’s ability to move farther throughout the valley than they previously had.

One manuscript that is particularly interesting is, 12.73 item 27, a letter between Thomas Mifflin to Clement Biddle, for it displays a contract to lay and upkeep a road adjoining Stockport and Harmony townships.

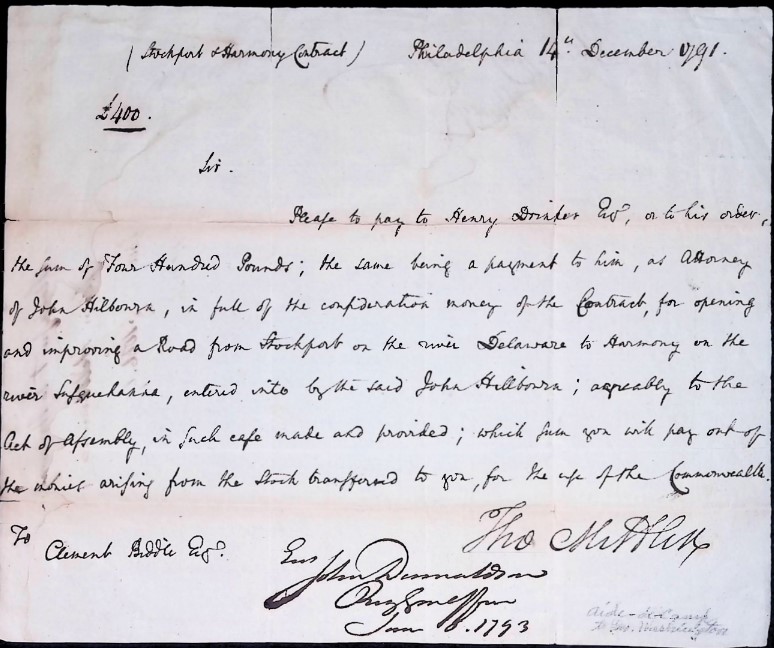

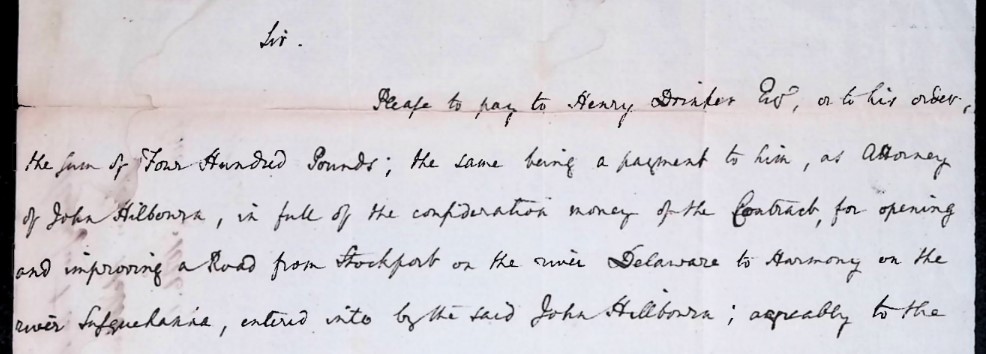

12.73. Item 27: Letter from Thomas Mifflin to Clement Biddle, 1791 December 14.

(Stockport & Harmony Contract) Philadelphia 14.th December 1791

£400.

Sir.

Please to pay to Henry Drinker Esq, or to his order, the sum of Four Hundred Pounds; the same being a payment to him, as Attorney of John Hillbourne, in full of the consideration money of the Contract, for opening and improving a Road from Stockport on the river Delaware to Harmony on the river Susquehanna, entered into by the said John Hillbourne; agreeably to the Act of Assembly, in such case made and provided; which sum you will pay out of the monies arriving from stock transferred to you, for the case of the Commonwealth.

To

Clement Biddle Esq. E– Tho[sic] Mifflin

John Donnaldson

Reg S—–

Jan 18. 1793

{Aide-de-camp

To Geo. Washington}

{back}

Recd [Received]. payment

Henry Drinker

Stockport to Harmony

John Hillbourne

£400 -1066.67

No 45’6

The manuscript demonstrates the growth of the valley during this period, as the roads extend beyond the needs of the residents and seek avenues to connect multiple towns together. In the letter, not only is a road being contracted, but it has been addressed as a service and trade of its own.

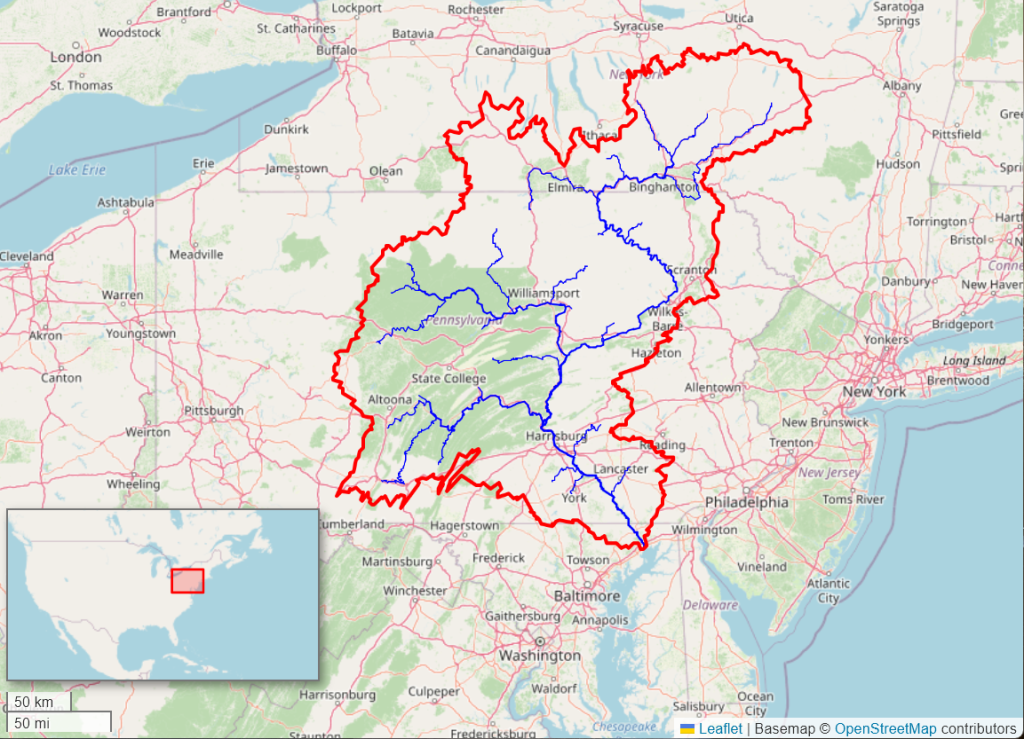

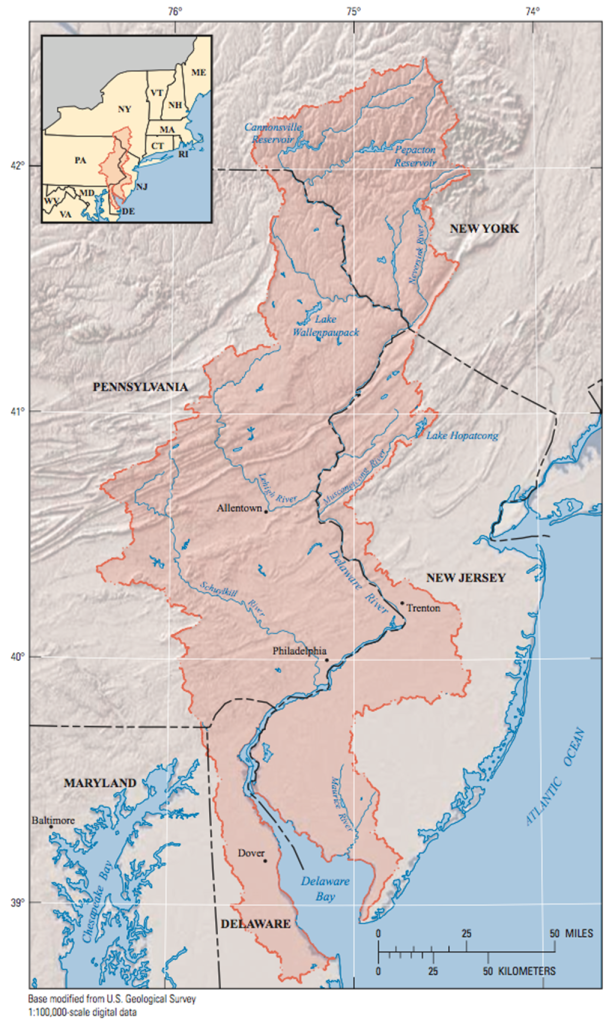

There is another incredibly interesting aspect to this road that we have not seen in the earlier 1772 manuscripts. Henry Drinker is being commissioned to lay a road spanning the valley across or around not one river, but two: the Delaware and the Susquehanna.

It would be a great distance alone to consider spanning both of these rivers, as they are situated a great deal apart from one another, with the Delaware River along the most Eastern part of the state.

Wikipedia; ACD May 2024

USGS; ACD May 2024

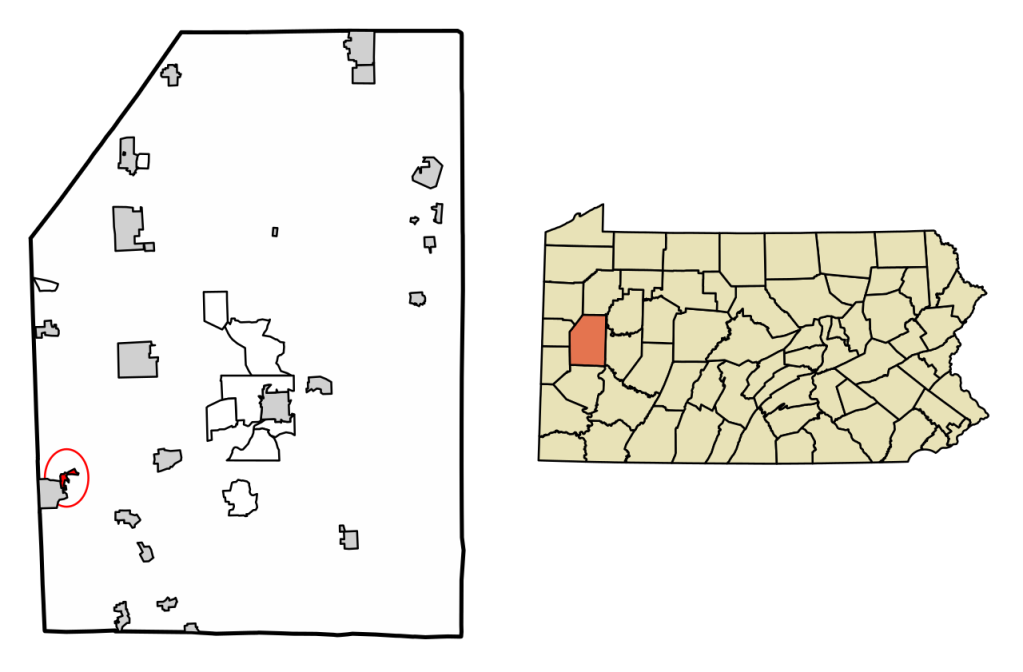

However, if you look at the two townships mentioned in the manuscript, you come to learn that they are an even greater distance.

Wikipedia; ACD May 2024

Wikipedia; ACD ay 2024

The maps above indicate that this road could have served as a crucial route spanning the heart of the state. The construction of it would have enhanced transportation in the valley and opened up new mercantile opportunities. Drinker’s proposed route likely provided a more direct connection between the region and two major rivers, simplifying travel compared to the complex system of bridges and ferries used to cross the waterways. This may be an early interaction of an up-and-coming industry within the valley, one that shortly predates the railroad but revolutionizes travel through the valley: turnpikes.

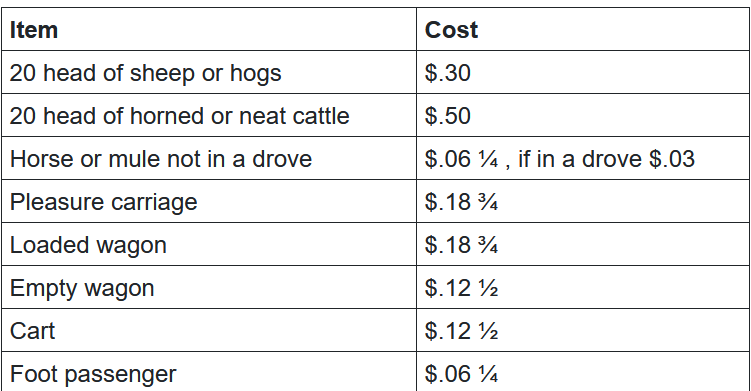

Turnpikes and Industrialization in the Valley

Traveling was a difficult venture for those in the valley since the earliest settlements. With the river being the chief mode of transport, people began to find ways that were more efficient and accessible for all parties to travel, such as building bridges and roads to connect nearby townships. However, as trade and mercantilism continued to prosper in the valley, people sought ways to improve travel not by townships, but by counties. Thus, we see the development and creation of turnpikes in the valley!

Ca. 1850 by Edwin Whitefield (1816–92)

Library of Congress; ACD May 2024

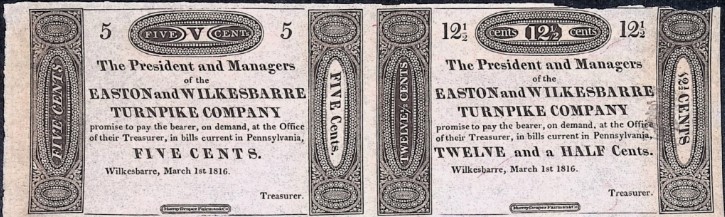

Today, turnpikes are state run roads that offer an expressway while traveling. Yet, in their earliest interactions in the valley they were privately owned and operated businesses! A turnpike company would typically request a loan from the local government or use personal funds to establish a dirt road that would run throughout and beyond the region. People could then buy ticket bills from the company booths to continue on the road, much like a modern toll booth.

in order to collect tolls.

Image/Courtesy of MTSU Center for Historic Preservation

National Park Service; ACD May 2024

National Park Service; ACD May 2024

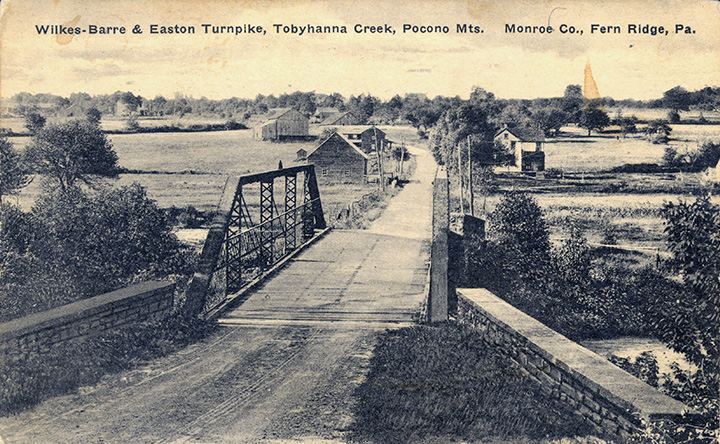

One of the earliest turnpikes in the valley was the Easton & Wilkes Barre Turnpike. It was the first major road along the western region of the township, and thus, a pivotal trade route in Pennsylvania. It began construction in 1816 until about 1860 when it was replaced with railroads. It was a highly popular route for it opened up a greater portion of the valley than had ever been seen before.

As seen from Monroe County, Fern Ridge, Pa

Historical Association of Tobyhanna Township; ACD May 2024

It followed the course of today’s route 115 in our township, with tollgates about every 17-miles. Grain from the Wyoming Valley, lumber from the Poconos, and building plaster from NY State all moved on the turnpike, as did stagecoaches with US Mail. By 1860, railroads were the preferred mode for moving freight, causing the turnpike to become a public road.

Wilkes Library Archives has an in-depth blog explaining financial manuscripts of the valley, and one of the items in the blog explains a travel voucher for the Easton & Wilkes Barre Turnpike. You can find that blog here.

Financial Manuscripts and Ephemera Series, 1776-1977,

of the Gilbert Stuart McClintock Collection

E.S. Farley Library Archives; ACD May 2024

An intriguing part of this collection is the depiction of local governments actively engaging in and financially supporting these pivotal industries. Over time, the turnpikes, similarly to bridges, were acquired and integrated into state infrastructure, making smoother transportation easily facilitated. These manuscripts provide insight into the early stages of this transferring of power, revealing the significant involvement and assistance provided by state officials.

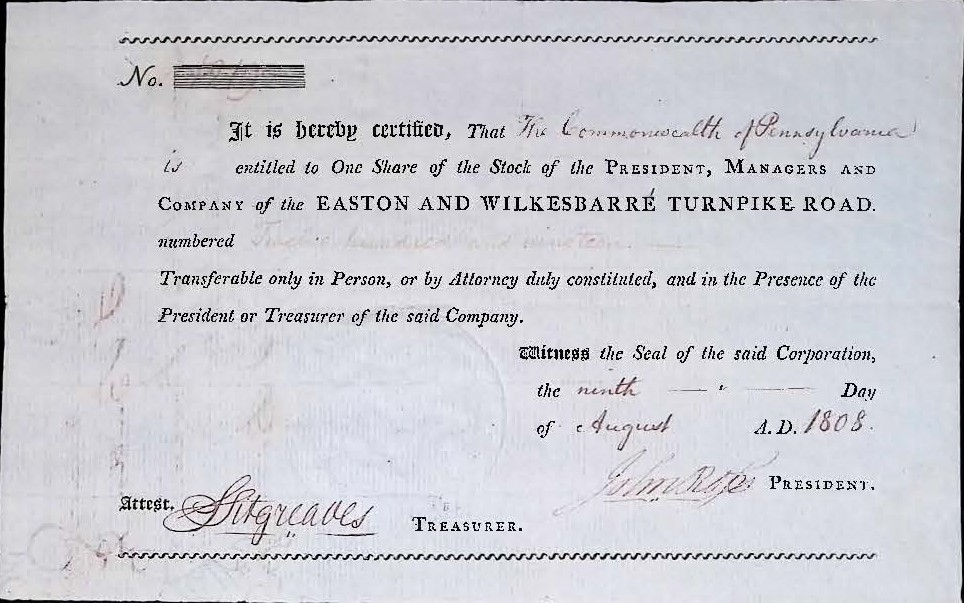

12.81a. Item 35a: Certificate from John Ross for “The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,” 1808 August 9.

No. 1219

It is hereby certified, That The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is entitled to One Share of the Stock of the President Managers and Company of the EASTON AND WILKES BARRE TURNPIKE ROAD numbered Twelve Hundred and nineteen —

Transferable only in Person, or by Attorney duly constituted, and in Presence of the President or Treasurer of said Company.

Witness the Seal of the said Corporation the ninth— day of August A.D 1808

John Ross President

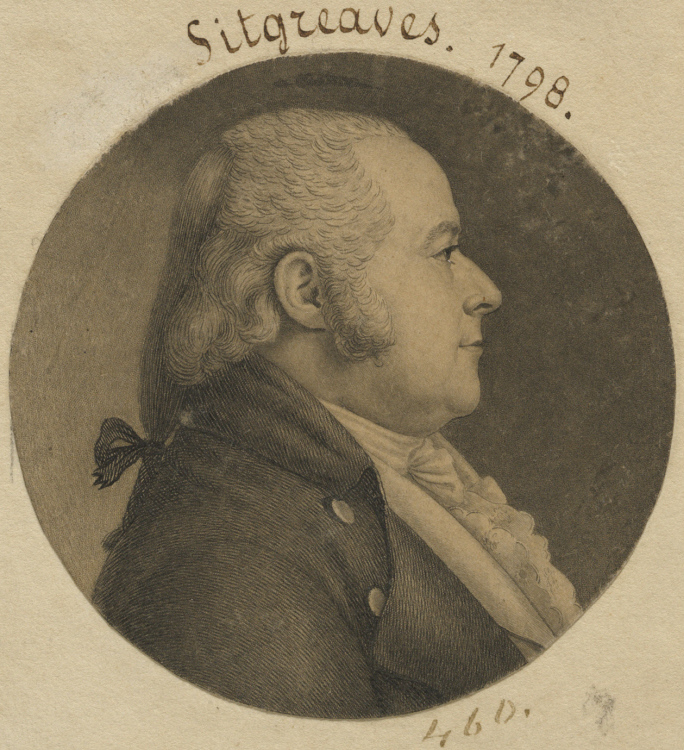

Attest, Sitgreaves Treasurer

{back}

July 13 1843

Transferred to Geo M. Hollenback

S Butler —

Dec. 22 1843- Transferred to Saml U. Cit

S. Butler —

The certificate specified that The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania was the owner of one share of the stock for the Eastern and Wilkes-Barre Turnpike Road. Commonly during the time period, people invested in shares of stocks for newly established turnpike roads.

Artist Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin

Wikipedia; ACD May 2024

The manuscript is signed by John Ross who served as a member of the Pennsylvania State House of Representatives in 1800, and the country register in 1808. It is also attested to by Samuel Sitgreaves, the county treasurer. He was heavily involved in transportation and agriculture. He was largely responsible for the erection of the first bridge across the Delaware River at the foot of Northampton Street in 1806 which resulted in a large volume of covered wagon traffic headed west through Easton.

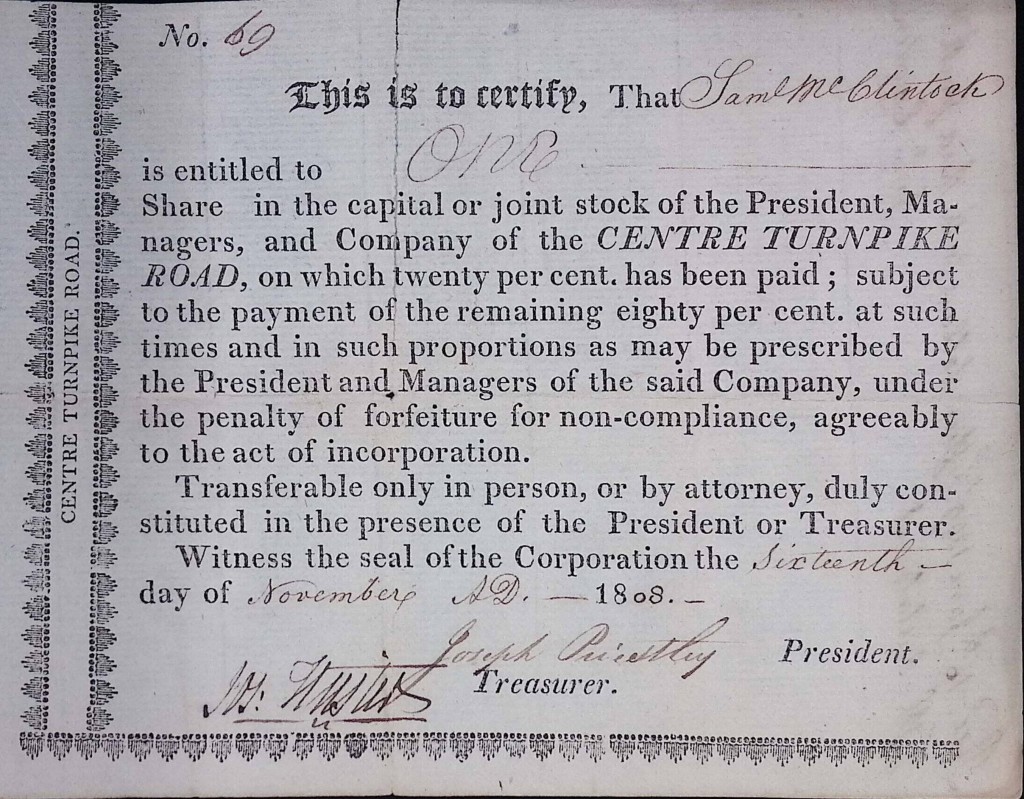

12.81b. Item 35b: Certificate from Joseph Priestley for Samuel McClintock, 1808 November 16.

We also have a similar manuscript where an individual bought a share in the construction and operation of a turnpike, Samuel McClintock, who invested in the Center turnpike. 12.81b item 35b depicts the same principle as we see in the manuscript above regarding the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, except this instance highlights how investment was becoming another industry within the valley.

12.81b. Item 35b: Certificate from Joseph Priestley for Samuel McClintock, 1808 November 16.

Financial backing like that from the Commonwealths or McClintocks eased the burden of first constructing the turnpikes as it required less money from a singular source. Wyoming Valley figures like Sitgreaves and McClintock also show how personal interests in particular industries influenced the governing powers of the county. The interests and actions of the valley shift to incorporate enterprises that build off of one another, never highlighting a singular industry but seeking how one may advantage the other: just as the development of merchants in the valley propelled a need for transportation.

We can see how the economic strength of the valley was stimulated beyond those first names, such as Hollenback, as the very local governing bodies were stimulated by a similar interest and party.

Petitions and the Use of Local Government

While it is intriguing to observe how our various regions have exhibited similar patterns in establishing their governments, pursuing diverse entrepreneurial and aid opportunities, what truly stands out is the manner in which individuals balanced the valley’s improvements to aid themselves.

One manuscript that explores a personal appeal by Hollenback concerning his health and autonomy.

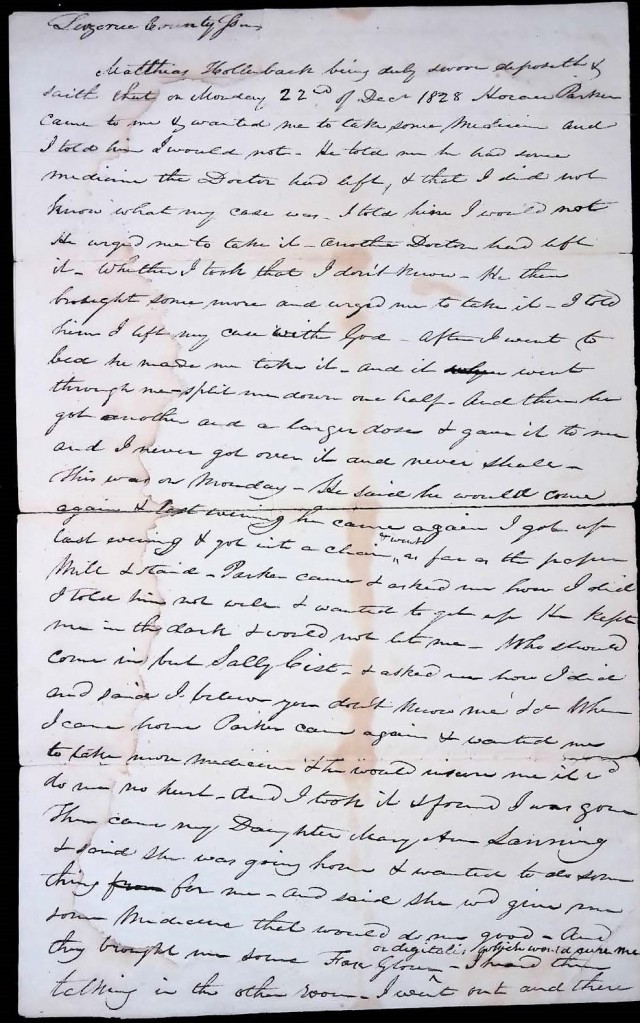

12.84. Item 38: Testimony by Matthias Hollenback in Suit Against Horace Parker, 1828 December 22.

Luzerne County Ss. [Sheriff Station]

Matthias Hollenback being duly sworn deposeth & saith that on Monday 22nd of Decr [December] 1828 Horace Parker came to me & wanted me to take some medicine and I told him I would not. He told me he had some medicine the Doctor had left, & that I did not know what my case was. I told him I would not He urged me to take it. Another Doctor had left it. Whether I took that I don’t know. – He then brought some more and urged me to take it. — I told him I left my case with God.- After I went to bed he made me take it and it

Back:

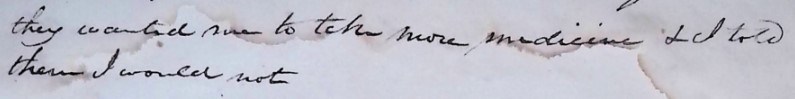

sat Eleazar Blackman & David Collings and they wanted me to take more medicine & I told them I would not

[End of transcript]

In the testimony, Matthias Hollenback explains how he has requested his friends and doctor to not be given medicine, digitalis, multiple times but has been ignored by those around him. Hollenback states that he has been bedridden after taking the medicine each time, awakening to hear others speaking with Parker through the walls. He also mentions having visits from his daughter, Mary Ann Lanning, Sally Cist, Eleazar Blackman, and David Collings who would continue to administer the medicine.

It is interesting as the manuscript is unlike any other legal appeal we have in our holdings, as it seeks approval to manage one’s own health care. The language is very personal, sharing how Hollenback has been taken over by the medicine and made to forget pieces of his day after being subjected to it.

Whether I took that I don’t know.”

He also presents a very reasonable account of his interactions, demonstrating how he has advocated for himself but has been disregarded. It is a very touching and emotive letter to read, as you can really feel the tension that the man holds in being overridden by those around him regarding his own health.

Though the letter is unfinished, it appears as if the intention of his testimony was to receive approval to take over his own medical treatments moving forward. He finished the letter with a simple directive that he had refused to take the medicine. However, the line feels cut off, as if they were either stopped or their illness cut them off in this particular letter.

Hollenback repeatedly mentions that his requests have gone unheard by those he is close to and it is sad, yes, but the opportunity to present one’s case for autonomy during the early stages of the valley’s growth gave me a better understanding of the day to day realities that residents faced during this time period. This letter made me think of our own appeal system regarding our health and autonomy. This letter felt very modern, as it still remains a conflicted topic within healthcare as to whether a patient can advocate for a certain level of nonresponse or nontreatment.

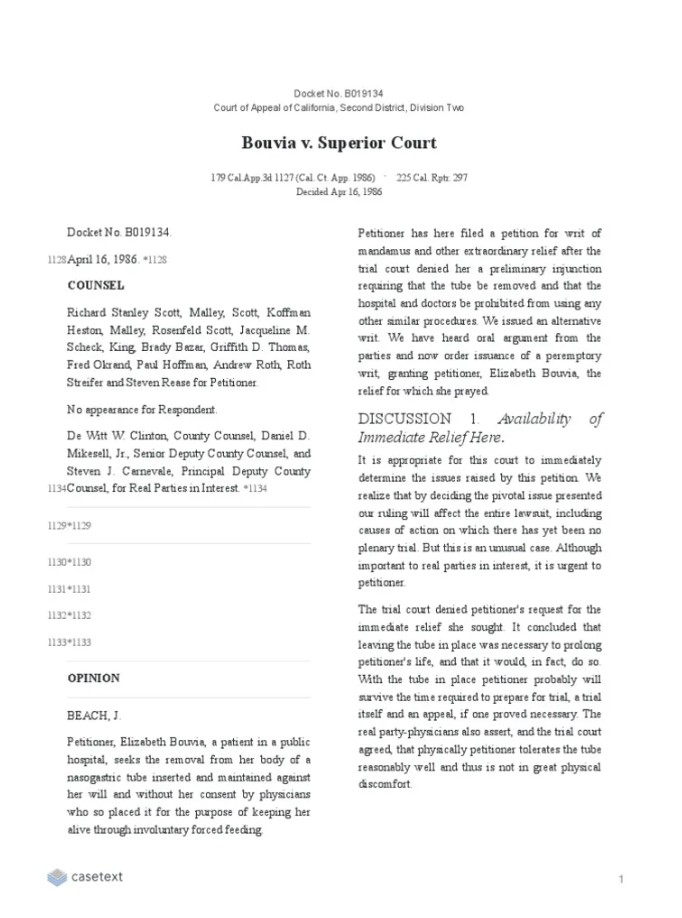

Even as recent as the late twentieth century, the question of patient autonomy and the right to refuse treatment has been a hotly contested debate. In 1985, Elizabeth Bouvia attempted to sue the hospital where she was admitted for refusing her right to end treatment. Bouvia was a young woman who was diagnosed with cerebral palsy, which advanced so greatly that she became completely bedridden. At the age of twenty six, she had expressed to her doctors a wish to desist treatment and receive end-of-life care, which, though she was mentally competent they refused her. She attempted to take matters into her own hands by refusing to eat, but the hospital requested an issue to insert a nasogastric tube regardless of Bouvia’s consent.

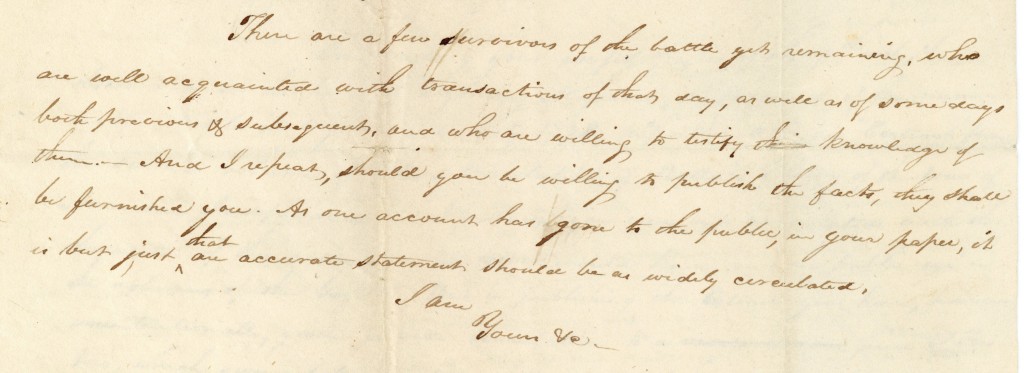

by Yan Chen on Prezi, found on Getty Images; ACD May 2024